Fighting Ebola: Antidepressant and Heart Drug Show Promise

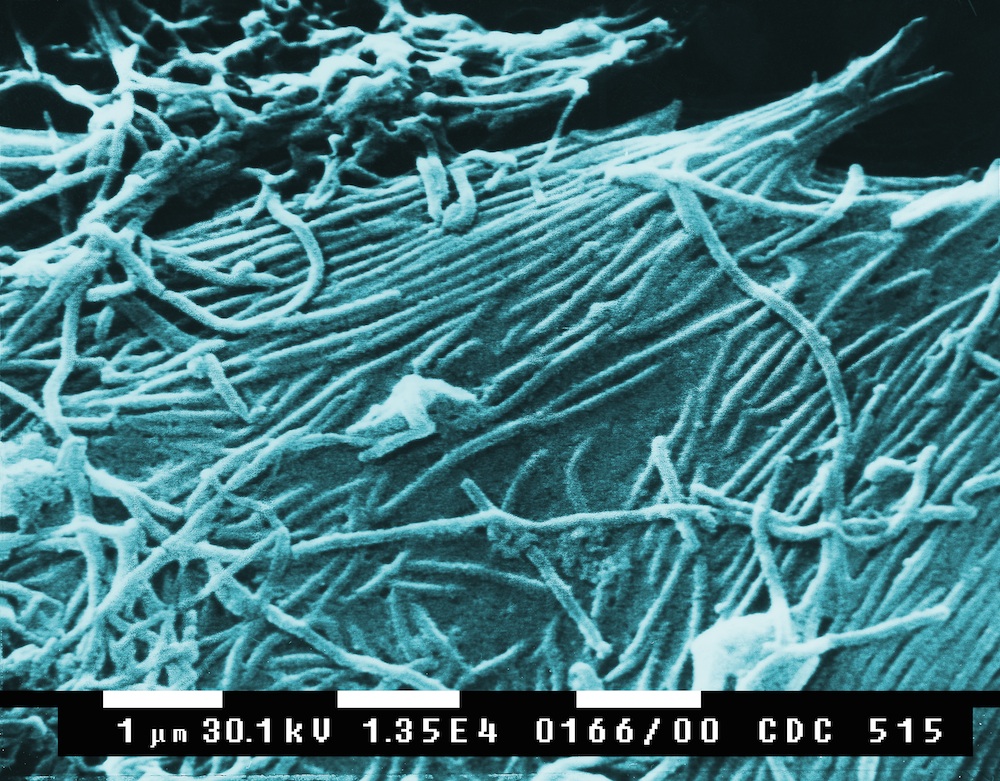

Two drugs approved for use in people — an antidepressant and a heart drug — might hold promise for treating Ebola, a new study in mice suggests.

The researchers screened about 2,600 compounds for their ability to hinder Ebola virus activity, and found 30 drugs that were effective against the virus in a lab dish. Two of the drugs appeared particularly promising for their action against Ebola — the antidepressant sertraline (brand name Zoloft) and a heart drug called bepridil (brand name Vascor).

These drugs were able to protect against Ebola in mice infected with the disease. In experiments, 70 percent of mice treated with sertraline, and 100 percent of mice treated with bepridil, survived an Ebola infection. In contrast, all the mice that were not treated died from Ebola in about a week.

"The current Ebola virus disease epidemic in Western Africa, the largest outbreak on record, underscores the urgent need for therapeutic as well as prophylactic interventions that can be easily distributed to patients, healthcare workers, and the general population," the researchers wrote in the June 3 issue of the journal Science Translational Medicine.

"During an outbreak, when we have little time to develop a new drug," repurposing existing drugs can allow researchers to respond quickly, said study co-author Gene Olinger, of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. Because the two drugs identified in the new study are already approved for use in people, they have the potential to be rapidly advanced to testing in Ebola patients, the researchers said. [The 9 Deadliest Viruses on Earth]

The researchers originally wanted to develop a way to screen drugs quickly for their potential activity against viruses. They previously found that two other drugs — clomiphene, which treats infertility in women, and toremifene, a drug for breast cancer — also block Ebola in mice.

Those drugs, as well as the two drugs identified in the new study, appear to inhibit Ebola infection by preventing the virus' genetic material from getting inside the host's cells.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

However, because these drugs were tested only in lab dishes and in mice, it's too soon to know how effective they would be in people with Ebola. The researchers noted that, when people take these drugs, the concentration of drugs in the blood may not be high enough to have the effect on the virus.

Still, some of the drugs tested in the study were originally intended to be taken for long periods, and so there is hope that it would be safe for people with Ebola to take higher doses of the drugs, because Ebola patients would need to take the drugs for only a short time, the researchers said.

Although these drugs are approved for use in people, they still have side effects that doctors will need to consider. The drug bepridil has been linked with fast or irregular beating in the heart's lower chambers, a potentially dangerous side effect.

The risk-to-benefit ratio of using bepridil to treat or prevent Ebola infection "will need to be considered," the researchers wrote. Because of its potential effects on the heart, it's possible that bepridil would not be given to patients in the later stages of the disease, Olinger said.

But to better understand the potential for these drugs to treat Ebola in people, additional studies of the drugs are first needed in nonhuman primates infected with the virus, the researchers said. Follow-up research has already found that combinations of drugs, rather than a single drug, might work better against Ebola, because the drugs have a synergistic effect, Olinger said.

Researchers at the U.S. Army Medical Research Institute of Infectious Diseases and the biotechnology company Horizon Discovery, which helps develop drug discovery research tools, also worked on the study. The U.S. Army Medical Research Institute of Infectious Diseases and Horizon Discovery hold a patent that covers potential combinations of drugs for Ebola.

Follow Rachael Rettner @RachaelRettner. FollowLive Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Rachael is a Live Science contributor, and was a former channel editor and senior writer for Live Science between 2010 and 2022. She has a master's degree in journalism from New York University's Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program. She also holds a B.S. in molecular biology and an M.S. in biology from the University of California, San Diego. Her work has appeared in Scienceline, The Washington Post and Scientific American.