Outbreak Like Mexican Swine Flu Predicted 14 Months Ago

A team of scientists predicted more than a year ago that Mexico and other tropical locales were emerging "hotspots" for so-called zoonotic diseases that jump from animals to humans, getting it right on the newly reported swine flu. This week, the scientists are analyzing the patterns of the new swine flu virus's spread and trying to predict its next moves. The researchers "should have preliminary findings by the weekend," team leader Peter Daszak of the Wildlife Trust told LiveScience. Daszak and his colleagues cautioned in February 2008 that infectious disease-fighting resources are not effectively deployed around the globe and that the U.S. government has not always accurately investigated how flu strains will arrive here. Hot spots The tropics prediction came from an analysis of 335 "disease events" involving emerging infectious diseases between 1940 and 2004 — examples include Ebola, HIV, yellow fever and SARS. The analysis showed that such events peaked in the 1980s and that the threat of these diseases to global health is increasing. The events, mostly caused by zoonotic diseases, were found to be correlated with socio-economic, environmental and ecological factors. That allowed the scientists to make a predictive map of where emerging diseases are most likely to emerge — pointing to Latin America, tropical Africa and Asia. The map also pointed up that global resources to fight disease emergence are misguided — focusing on richer, developed countries of Europe, North America, parts of Asia and Australia, rather than in developing countries. The report was published in the Feb. 21, 2008, issue of the journal Nature. The disease event prediction map is like an earthquake risk map, Daszak said. "If we live in one of these 'hotspots,' we need to protect ourselves, and our trading and traveling partners from the risk of new diseases," he said. Don't travel Earlier today, the European Union's health commissioner urged Europeans to avoid traveling to the United States and Canada unless it was essential. But Richard Besser, acting director of the U.S. Centers for Disease Control, disagreed, saying this level of concern was not called for. Along these lines, some Asian countries set up quarantines for airline passengers arriving there if authorities suspect travelers are sick, The New York Times reported. Then this afternoon, Besser revised his course and announced the CDC might issue a travel advisory warning U.S. residents against non-essential travel to Mexico, according to the Associated Press. Daszak recommends against all non-essential travel, particularly to regions where the new swine flu virus has spread or is suspected of spreading. The United States is one of those regions, it is now clear, so any individual's travel can have an impact on spreading the disease. A person can carry the flu virus and be contagious before symptoms appear. "This is a potentially significant event, and everyone can help reduce the size and impact of it. First, cut non-essential travel to Mexico and other regions," Daszak said. "Second, if you are sick, do not travel to work or other crowded places – visit your doctor and seek medication and treatment. Third, the simplest hygiene measures are the most effective – handwashing and covering our mouths when we cough." Viruses have evolved to exploit human contact as a way of spreading, Daszak pointed out. If we cut down on contact, we reduce the impact of an outbreak. Animals-to-humans Daszak and colleagues put out similar research two-plus years ago showing that Mexico, Brazil and Canada were the most likely routes of entry for avian influenza into the United States. The older study made clear that the federal government had been looking in the wrong place for the possible route that bird flu might travel to the United States from Asia. The U.S. surveillance program then was focusing on migratory birds flying from Asia to Alaska. The study, led by Marm Kilpatrick with the Consortium for Conservation Medicine, instead showed that bird flu was most likely to be introduced to the United States and other countries in the Western Hemisphere through the infected poultry trade. Subsequently, migrating birds from countries south of the United States would then bring the H5N1 avian influenza virus to the United States, the study found. The results were published in the Dec. 19, 2006, issue of the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. Biodiversity loss can also contribute to the spread of zoonoses, previous research has found, as it can increase the likelihood that humans will come into contact with other animals and the diseases they carry. AIDS, smallpox, and Ebola are all examples of pathogens that have made the animal-to-human leap, some more successfully than others. Some zoonotic diseases come from sources close to human homes: Measles, mumps, smallpox, influenza A and tuberculosis are all believed to have come from domestic animals as farmers came into close contact with them. Others have more "exotic" origins in wildlife, for example, the slaughter of wild animals for "bush meat." Climate change can impact disease emergence by shifting animal habitats and increasing the range of known disease carriers, such as mosquitoes. By researching the links between wildlife, livestock and humans, scientists can better identify the movement of many new disease-causing agents before they move to people, said Mary C. Pearl, president of Wildlife Trust and a co-founder of the Consortium for Conservation Medicine. Events are predictable It is possible to move beyond the conventional "surveillance and response" mode to one of "prediction and prevention," said Donald Burke, dean of the University of Pittsburgh Graduate School of Public Health, who was not an author of the 2006 study. Some experts claim that it's impossible to predict emergent infectious diseases, but Daszak and his colleagues beg to differ. "You're often up against a challenge that no one will ever solve, people say," when it comes to solving the problem of emerging infectious diseases, he told a panel discussion audience earlier this month at the American Museum of Natural History in New York. "No one knows where the next HIV will come from. Well, we did." Senior Writer Andrea Thompson contributed to this report.

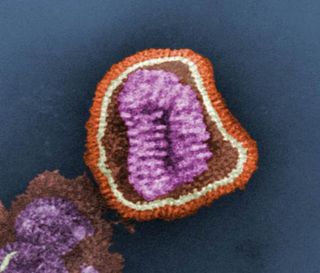

- Flu Basics

- Video: The Challenge of Making Flu Vaccines

- More Flu News & Information

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Robin Lloyd was a senior editor at Space.com and Live Science from 2007 to 2009. She holds a B.A. degree in sociology from Smith College and a Ph.D. and M.A. degree in sociology from the University of California at Santa Barbara. She is currently a freelance science writer based in New York City and a contributing editor at Scientific American, as well as an adjunct professor at New York University's Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program.

Most Popular