FDA Working to Replace Misleading Food Labels

NEW YORK — The aisles of American supermarkets can be bewildering places these days, lined with dozens of variations of cereals, crackers, chips and other foods, many of which boast of their supposed healthfulness — this yogurt is "low fat," while this cereal is "heart healthy," and those chips have "0 grams trans fat." What claims are the conscientious eater to trust and what foods should they pick to put on their table?

This question has become harder and harder for shoppers to answer, as health problems associated with poor diets, such as heart disease and obesity, affect more U.S. residents each year. Meanwhile, studies show that Americans want more and better guidance on what foods to eat.

"The public is demonstrably confused about what to eat," said Marion Nestle, a nutritionist at New York University, who recently gave a talk here at the New York Academy of Sciences about diet and food politics.

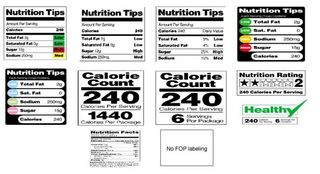

The rising obesity epidemic in the United States (more than 30 percent of U.S. adults are now obese), combined with the proliferation of various labeling schemes and the worries about the potentially misleading nature of some of these schemes, has prompted the U.S. Food and Drug Administration to conduct a review of so-called front-of-package labeling. The aim is to come up with a standard set of regulations that would govern what claims manufacturers can make on these food labels.

"We had noticed a real proliferation of these front-of-package symbols, and noticed that there were a lot of different ones," said Siobhan DeLancey, an FDA spokesperson. "And there didn't seem to be any rule of thumb or real consistency for consumers to be able to depend on."

The FDA and nutrition advocates hope the review will remedy this situation and provide consumers with a standard system of labels they can rely on to make choices about what foods they buy.

"The FDA is taking a good, hard look at the entire front-of-package situation," Nestle said.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Labels, labels everywhere

Claims like "low fat" and "high in fiber" didn't begin to show up much on the fronts of food packages until around 1994, when the Nutrition Facts panel was required for every food package, under the provisions of the 1990 Nutrition Labeling and Education Act.

"Until then, the FDA said that health claims were drug claims and food companies had to do what drug companies have to: prove safety and effectiveness," Nestle told LiveScience.

But manufacturers argued that since they were required to put potentially negative nutrition information on their foods (for example, the number of calories or grams of fat), they should also be allowed to point out their product's positives. Congress agreed and told the FDA to allow health claims that were backed up by a reasonable amount of science, Nestle said. After that, front-of-package claims exploded.

"There are health claims on everything," Nestle said.

DeLancey said criteria must be met for foods to bear claims such as "high in fiber" or "low in salt" — fiber in the food must be above a certain amount and salt below a certain amount. But when such claims appear on many breakfast cereals and snack foods that may also be high in sugar or calories, the result can be consumer confusion and consumption of foods that aren't actually healthy, Nestle said.

"Most people get their nutrition information from food marketers, and that information is not exactly unbiased," Nestle said.

Studies seem to at least partly back up this worry. The FDA's 2008 Health and Diet Survey — a random phone survey of more than 2,500 adults from all 50 states and the District of Columbia — looked at how Americans use and view front-of-package labels. It found that more than half read food labels when they first pick up a package — up 10 percent from 2001.

For claims such as "low fat," "high fiber," and "cholesterol-free," 38 percent of respondents said they often used such claims, while 34 percent said they did sometimes. The survey found that 41 percent of respondents trust that all or most of the nutrient claims such as "low fat" or "high fiber" are accurate, while 56 percent believe that some or none of them are accurate, pointing to confusion on the part of consumers over what labels they can trust.

An online survey of 1,045 adults by FoodMinds — a food and nutrition company — found U.S. consumers seem to want the government to help clear up the confusion. Their survey, conducted in January this year, found that 86 percent of respondents were interested in the government implementing objective front-of-package labeling that highlights calories and beneficial nutrients in a food. And 77 percent were interested in labels that would warn them when a food was high calorie and low in nutrients; 64 percent said they would eat less of or stop buying a food that had such a warning.

Smart choices

The situation reached something of a head when in September of last year, The New York Times wrote an article about the Smart Choices program — a voluntary labeling program used by several companies in collaboration — and how the label that was supposed to indicate foods that were healthy choices ended up appearing on a box of Fruit Loops, among other less-than-healthy options.

The attention brought to labeling by this and other articles, complaints from consumers and advocates, and the sheer number of labeling schemes being used prompted the FDA to send out warning letters to some manufacturers in October 2009 asking them to review their own labels for accuracy. The FDA also notified the companies the FDA would begin its own review of such schemes. (Smart Choices was voluntarily suspended in October pending the FDA review.)

"We didn't ask anybody to take them off the market, but we said, 'Look, you need to do a review of these and ensure that they're really accurate,'" DeLancey said.

Review in progress

The FDA is currently in the middle of the review process, which involves both looking at existing and proposed labeling schemes for accuracy, and conducting surveys of consumers to find out what they want from such schemes.

The key, DeLancey told LiveScience, is to find out "what consumers are going to find the most useful and that's actually going to give them accurate information."

Various labeling schemes have been used and proposed: Some list just a couple key points of nutrition, such as calories, accompanied by a check mark or other symbol; some are a truncated version of the Nutrition Facts label that show key points, such as calories, fat, sugar and sodium; others include on top of that information a "traffic light" symbol (something that has been used with success in the United Kingdom) by each nutrient that indicates whether that nutrient is in the acceptable range (green) or not (red).

The U.S. Institute of Medicine (IOM) is reviewing some of these schemes and any studies that have been done on food labels to see how accurate and informative they are. The IOM committee acts as an impartial, non-government source that regularly advises on the scientific issues involved in such matters. The IOM is slated to complete their report later this year.

Working with consumers is also important because the FDA wants to make sure that any schemes they pick or regulations they set will result in a system that consumers will actually use, that they can use for quick reference and will give them accurate information.

"We're looking at ways to give them the information in a more easily digestible" format, DeLancey said.

DeLancey noted a phenomenon called the "truncation effect" as one consideration in any scheme: Customers might be in a hurry to get dinner on the table or have kids they're trying to keep an eye on, and "that keeps people from turning around and looking at the Nutrition Facts label." So the easier-to-use and more accurate any scheme is, the more likely it is to result in a shopper picking a healthy food option.

DeLancey says that the FDA has talked with industries as well, "and they are actually pretty supportive."

The final word on food labels

The consumer studies the FDA is conducting are slated to finish at the end of this year or the beginning of next. The next step will be to use the information from these and the IOM report to come up with a draft set of regulations to govern front-of-package labeling, to be published in the Federal Register, and then open that draft up to a period of public comment. Once any "substantive" comments (those that make legitimate suggestions and critiques) have been addressed, the FDA can adopt the regulation.

Whether the end result will be a specific labeling scheme or a set of regulations over just what can or must be on the front of a package isn't yet decided.

"We haven't decided yet whether there's going to be one universal symbol, because we may find that there are certain products that need a different kind of symbol, like beverages versus traditional food," DeLancey said. "But there will be one set of criteria for using it."

Ultimately, no matter what kind of labeling system or regulations are set up, the burden of picking a better diet rests with the individual consumer.

"Nobody can regulate what people actually eat, you can only give them the information, the accurate information to make their own choices," DeLancey said.

If you ask Nestle, she doesn't like any food labeling schemes, noting that junk food is junk food, no matter what nutrients might be added to it. Her tips for a healthier diet are: "Eat less; move more; eat fruits and veggies; don't eat too much junk food; enjoy."

- Top 10 Good Foods Gone Bad

- What's The Single Best Food to Eat?

- Take the Nutrition Quiz

Andrea Thompson is an associate editor at Scientific American, where she covers sustainability, energy and the environment. Prior to that, she was a senior writer covering climate science at Climate Central and a reporter and editor at Live Science, where she primarily covered Earth science and the environment. She holds a graduate degree in science health and environmental reporting from New York University, as well as a bachelor of science and and masters of science in atmospheric chemistry from the Georgia Institute of Technology.

Most Popular