1,500-Year-Old Quran Manuscript Could Be Oldest Known Copy

A 1,500-year-old parchment could be one of the oldest known copies of the Quran, possibly dating back to a time that overlapped with the life of the Prophet Muhammad, according to researchers who recently dated the manuscript fragments.

The text underwent radiocarbon dating, which measured the age of the find's organic materials. Researchers at the University of Birmingham, in the United Kingdom, found that the leaves of parchment date back to A.D. 568 and A.D. 645.

"The radiocarbon dating has delivered an exciting result, which contributes significantly to our understanding of the earliest written copies of the Quran," Susan Worrall, director of special collections at the University of Birmingham, said in a statement. [The Holy Land: 7 Amazing Archaeological Finds]

The Prophet Muhammad is thought to have lived between A.D. 570 and A.D. 632, and according to Muslim tradition, he received the revelations that make up the Quran between A.D. 610 and A.D. 632. The divine message was not written at that time, though. "Instead, the revelations were preserved in the 'memories of men,'" said David Thomas and Nadir Dinshaw, both religious professors at the University of Birmingham.

The radiocarbon dates from the parchment indicate that the animal that provided the parchment lived during or right after the lifetime of Muhammad. "This means that the parts of the Quran that are written on the parchment can, with a degree of confidence, be dated to less than two decades after Muhammad's death," Thomas and Dinshaw said.

The parchment likely came from the skin of a calf, goat or sheep, the researchers said. The skin would have been first cleaned of any hair or flesh and then stretched on a wooden frame. As the skin is stretched, the parchment maker scrapes the surface with a curved knife, wets the skin and dries it in rotation several times to bring the parchment to an ideal thickness and tightness.

Researchers dated the parchmentby measuring the radioactive decay of carbon-14, a common way to determine the age of ancient papers and parchments. Carbon isotopes, or carbon atoms of varying weight, float around in relatively constant proportions in Earth's atmosphere, and all living things have the same ratio of stable carbon to radioactive carbon-14. When an organism dies, the radioactive carbon decays at predictable rates over time, which means researchers can examine the remaining levels of carbon-14 to make age estimates.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Ancient text

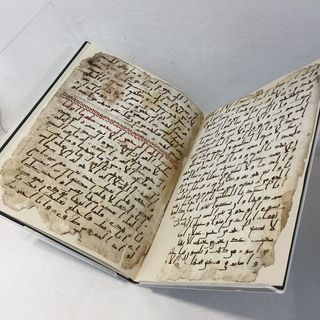

The Quran manuscript covers two parchment leaves and contains parts of the suras (chapters) 18 through 20, written with ink in an early form of Arabic script called Hijazi. The manuscript had been improperly bound with leaves of a similar Quran manuscript that dated to the late 7th century. That text was kept in the University of Birmingham's Mingana Collection of Middle Eastern manuscripts, held in the Cadbury Research Library.

Although most of the divine revelations received by the Prophet Muhammad were committed to memory, parts were written down on parchment, stone, palm leaves and the shoulder blades of camels, the researchers said. "Caliph Abu Bakr, the first leader of the Muslim community after Muhammad, ordered the collection of all Quranic material in the form of a book," Thomas and Dinshaw said.

The final written version, considered the authoritative account, was completed under the direction of Caliph Uthman ibn Affan, the third leader of the Muslim community, in about A.D. 650, and was distributed to the main cities under Muslim rule.

"Muslims believe that the Quran they read today is the same text that was standardized under Uthman, and regard it as the exact record of the revelations that were delivered to Muhammad," Thomas and Dinshaw said.

"This is indeed an exciting discovery," said Muhammad Isa Waley, lead curator for Persian and Turkish manuscripts at the British Library. "The Muslim communitywas not wealthy enough to stockpile animal skins for decades, and to produce a complete Mushaf, or copy, of the Holy Qur'an required a great many of them," he added.

"This — along with the sheer beauty of the content and the surprisingly clear Hijazi script — is news to rejoice Muslim hearts," Waley said.

Elizabeth Goldbaum is on Twitter. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.