100 Years of Women in Politics: How They've Served

One hundred years ago today, on March 4, 1917, Rep. Jeannette Rankin, R-Mont., became the first woman to serve in the U.S. Congress.

Rankin's election was extraordinary, as it happened about three years before U.S. women had the right to vote. But although she herself couldn't vote at the time, Rankin found that there were no laws restricting women from holding federal office. [10 Amazing Women You Won't Find in History Books]

"I may be the first woman member of Congress," she said following her election in 1916, according to the History, Art & Archives of the U.S. House of Representatives. "But I won't be the last."

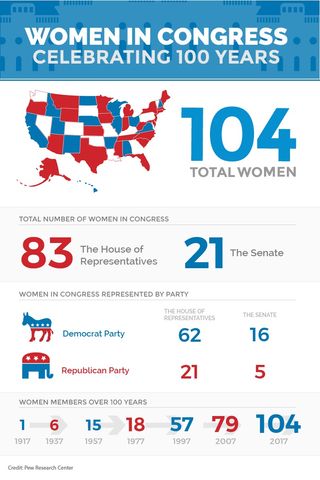

Rankin's prediction came true: She certainly wasn't the last woman to serve in Congress. But women, who constitute 50.8 percent of the U.S. population, are still underrepresented in the Senate and House. This year, women hold 104 (19.4 percent) of the nation's 535 congressional seats, according to Rutgers University. Of those, 21 women are in the Senate and 83 are in the House.

How they got there

Rankin's achievement was remarkable for another reason: She was elected, not appointed. In the following decades, other women served in federal office, but they usually got there in a more roundabout way.

In 1922, Rebecca Latimer Felton, a Democrat from Georgia, became the first female senator. But the 87-year-old was appointed, and she served for just 24 hours. The next female senator didn't serve until 1931, when Hattie Caraway, a Democrat from Arkansas, was appointed to fill her dead husband's seat. However, Caraway was subsequently elected to two six-year terms, according to the Congressional Research Service (CRS).

It wasn't until 1979 that a woman — Nancy Landon Kassebaum, a Republican from Kansas —won a Senate seat without previously filling a vacancy in an unexpired congressional seat, the CRS reported. (Under the U.S. Constitution, senators can serve an unlimited number of six-year terms, while Representatives can serve unlimited two-year terms.)

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

In 1992, the so-called "Year of the Woman," the number of female representatives went from 32 in the 102nd Congress to 54 in the 103rd, an uptick of nearly 69 percent, CRS said. (Another female senator joined that June, when Republican Kay Bailey Hutchison won a special election in Texas.)

There are several reasons for the sudden wave, said Michele Swers, a professor of government at Georgetown University in Washington, D.C.

The Cold War had just ended, leading to a focus on domestic policy, such as health care and women's issues, Swers said. Moreover, "Anita Hill was in the news because she had accused Clarence Thomas of sexually harassing her when he was the head of the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission. There was a lot of attention [paid] to that.

"There were several women that then ran, saying we need to have more women in Congress," Swers said. [7 Great Dramas in Congressional History]

Policies women pursued

With more women in Congress following the 1992 election, Swers decided she had enough data points to run a study on women's legislative priorities. She examined the bills that women sponsored and the projects they pursued.

"What I found, at the time, is that Democratic women and moderate Republican women were more likely to focus on issues related to women, children and families," Swers said. "That still holds today, except that now there are fewer moderate Republican women — there are fewer moderates in general."

Issues commonly considered women's issues include family and medical leave, violence against women, sexual harassment and abortion, Swers said.

"For the Family and Medical Leave Act [of 1993], which is the only thing we've done on family leave to date, which provides three months of unpaid leave, that was Pat Schroeder, a Democrat from Colorado, and Marge Roukema, a Republican from New Jersey, really pushing that bill forward," Swers said.

Moreover, Rep. Connie Morella, a moderate Republican from Maryland, was one of four main Republican co-sponsors of the Violence Against Women Act and "also introduced bills that were incorporated into larger laws, such as the National Domestic Violence Hotline Act and the Gender Equity in Math and Science Act," according to the Maryland State Archives.

Liberal and conservative female politicians are less likely to work together now than they were before, but they still find common ground, Swers said. For example, last year these politicians worked together on ways to prevent human trafficking, Swers said.

In addition, women in the Senate have periodic, nonpartisan dinners, a tradition started by former Sen. Barbara Mikulski (D-Md.), who orchestrated the gatherings to teach newcomers how to govern effectively and also to "forge some bonds of friendship," Swers said.

Original article on Live Science.

Laura is the archaeology and Life's Little Mysteries editor at Live Science. She also reports on general science, including paleontology. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.

Most Popular