Having Family for Dinner: 'Cannibalism' Author Dishes

When you think of cannibals, you may picture the headline-grabbing psychopaths who, every so often, commit horrific crimes.

But elsewhere in the animal kingdom, cannibalism might involve a self-sacrificing mother or a hungry fetus snacking down on its siblings.

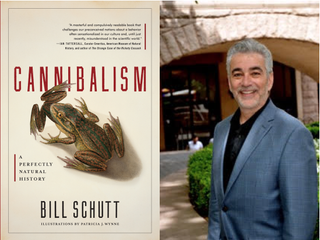

Now, Bill Schutt's "Cannibalism: A Perfectly Natural History" (Algonquin Books, 2017) shows just how prevalent, and just how diverse, cannibalism is among animals.

In one example, Schutt tells how the black lace-weaver spider (Amaurobius ferox) feeds her offspring her own eggs — and then her own body. In "an extreme act of parental care," she lowers herself onto her hungry little progeny, who then eat her alive and drain her of bodily fluids, Schutt writes. In another saga, Schutt describes how embryonic sand tiger sharks (Carcharias taurus) chow down on their siblings while still in the womb, making this shark the only known species to consume embryos in utero.

Schutt, a biology professor at Long Island University (LIU-Post) in New York and a research associate in residence at the American Museum of Natural History, recently spoke with Live Science about nature's colorful array of cannibals and what people's fascination with such cannibals may mean. (His answers have been edited for clarity and length.)

Live Science: How did you become interested in the topic of cannibalism?

Bill Schutt: I've always had a real interest in both natural history and the macabre, which is certainly why none of my friends or relatives were surprised that, once I became a zoologist, I chose to study bats. Likewise, nobody was shocked that my first nonfiction book, "Dark Banquet" [Crown, 2008], was all about blood-feeding creatures. [Photos: Best Wild Animal Selfies]

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Basically, I enjoy investigating subjects that seem horrific or disgusting (or both), then writing about them through the eyes of a zoologist. The topic of cannibalism seemed like an interesting topic to work on after blood feeding. And when I found all sorts of misinformation and an unfortunate, but understandable emphasis on sensationalism and gore, cannibalism turned out to be a perfect subject for me.

Live Science: What surprised you the most during your research on cannibalism?

Schutt: I was surprised at how common cannibalism is across the entire animal kingdom. There are literally thousands of species, from microbes to monkeys, that consume their own kind for all sorts of reasons that make perfect evolutionary sense. This isn't abnormal behavior. It's absolutely normal, and this also holds true in some of the most infamous cases of human cannibalism — the Donner Party, for example. [The Donner Party was a group of American pioneers who traveled west by wagon in the 1840s, only to become stuck in the Sierra Nevada during the winter. They resorted to cannibalism to survive.]

Live Science: Your book aims to debunk some common myths about cannibalism. What were some of the most prevalent myths you encountered?

Schutt: That cannibalism in the animal kingdom is rare and [that] it only happens in instances where you're dealing with abnormal behaviors, such as captive conditions or a lack of food. That was the party line among scientists for a long time, until probably starting in the 1970s, when they discovered that all sorts of different animals cannibalize for many different reasons that had nothing to do with stress or a lack of food. That, to me, was really interesting.

Live Science: You mention in your book that cannibalism serves a variety of functions in animals. Could you elaborate on a few?

Schutt: Cannibalism is sometimes done as an act of parental care. There are spiders, for example, that lay eggs that have not been fertilized, called trophic eggs, just for their newly hatched spiderlings to eat. But when these run out, the mother calls her offspring to her by drumming on their web. As she hunkers down, they climb all over her body and then they eat her alive, leaving a husk-like corpse.

Another function of cannibalism is that it helps animals survive in stressful environmental conditions. If there's suddenly a lack of alternative food options, many species will eat their young in order to survive to mate another day.

Live Science: What is the biggest difference between human and animal cannibalism?

Schutt: Western cultures, or those cultures that have been influenced by them (whether voluntarily or not), decided long ago that human cannibalism is probably the ultimate taboo. In societies where that concept wasn't determined to be a taboo or where Western rules weren't imposed on individuals, ideas about cannibalism turned out to be very different. For example, until relatively recently, there were indigenous groups in South America where people were as mortified at the concept of burying their dead as Western missionaries and anthropologists were about consuming their own departed loved ones.

In nature, there are no culture-generated rituals to either promote or fear. In many fish species, adults can be a million times larger than their own eggs. As a result, most fish exhibit about as much individual recognition of their offspring as humans do a handful of raisins. [Creative Creatures: 10 Animals That Use Tools]

Live Science: You also investigated whether the human taboo against cannibalism was biological or social. What did you find?

Schutt: I definitely came away thinking that there are aspects of both. It's no secret that culture plays a huge part in determining whether something is permissible (and even sacred) or forbidden. But I also came away with an understanding that there may very well be strong selection pressure for humans not to eat other humans.

One selection pressure against cannibalism in humans comes from diseases called spongiform encephalopathies, such as kuru, which destroy the brain and are always fatal. As with other versions of this disease — which can infect mink, sheep and, perhaps most infamously, cows — the human form can be caused by consuming infected tissue, especially nervous system tissue.

So cannibalism may have dire consequences for humans. Some researchers have even hypothesized, using computer modeling, that cannibalism — and the spread of a kuru-like disease — may have sped up the ultimate demise of the Neanderthals.

Live Science: Why do you think cannibalism continues to fascinate us? What does that fascination say about us?

Schutt: I think our deep fascination with the topic of cannibalism stems from the fact that, since the dawn of Western culture, we've been taught that it's arguably the worst thing that a person can do to another person. That in itself makes it both horrifying and interesting.

Add this ultimate taboo to the fact that most of us love a good scare, and you have an explanation for why Hannibal "the Cannibal" Lecter was voted the greatest screen villain of all time by the American Film Institute.

We're all fascinated with food as well, and with human cannibalism, I suppose many of us are dealing with the ultimate in scary food.

Really, the theme of this book is that you start off with these preconceived notions of what cannibalism is, and then when you explore it more, you find out that it is something completely different. That it makes all sorts of sense, in some ways, and that the examples that you find in the animal kingdom can be used to explain the circumstances behind some of the more infamous examples of human cannibalism. You can then look at those examples in a completely new light. That's one thing I'd like to get across.

"Cannibalism: A Perfectly Natural History" will be available on Feb. 14, 2017, and is available for pre-order now.

Originally published on Live Science.