Eating Brains: Cannibal Tribe Evolved Resistance to Fatal Disease

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

The practice of cannibalism in one Papua New Guinea tribe lead to the spread of a fatal brain disease called kuru that caused a devastating epidemic in the group. But now, some members of the tribe carry a gene that appears to protect against kuru, as well as other so-called "prion diseases," such as mad cow, a new study finds.

The findings could help researchers better understand these fatal brain diseases, and develop treatments for people who have the diseases, the researchers said.

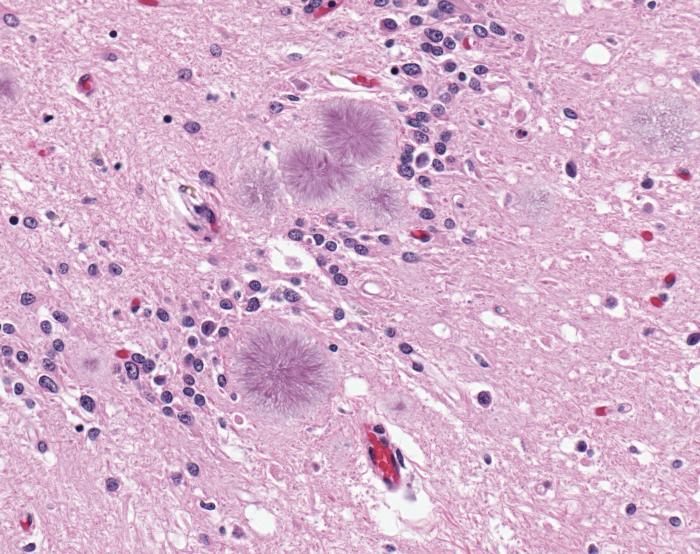

The Papua New Guinea tribe, known as the Fore people, used to conduct a funeral ritual that involved consuming the human brain. Early in the 20th century, tribe members began to develop kuru, a neurological disorder caused by infectious prions, which are proteins that fold abnormally and form lesions in the brain. This was the start of an epidemic of kuru among the Fore people, which at its peak in the 1950s, killed up to 2 percent of the tribe each year.

The tribe stopped practicing cannibalism in the late 1950s, which lead to a decline in kuru. But because the disease can take many years to show up, cases continued to appear for decades.

Recently, researchers discovered that some of the people who survived the kuru epidemic carry a genetic mutation called V127, whereas those who developed kuru did not have this mutation. This led the researchers to suspect that V127 conferred protection against the disease.

In a new study, researchers genetically engineered mice to have the V127 mutation, and then injected the animals with infectious prions. Results showed that mice with one copy of the 127V mutation were resistant to kuru, as well as a similar disease called classical Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease. Mice with two copies of V127 were resistant to those diseases, as well as another prion disease, called variant Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease, which is sometimes referred to as the "human form of mad cow disease."

Although the cessation of cannibalism among the Fore people led to a decline in kuru cases, the new study suggests that if the disease had continued to spread, the "region might have been repopulated with kuru-resistant individuals," the researchers wrote in the June 10 issue of the journal Nature. [10 Things You Didn't Know About the Brain]

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

It's important to note that the practice of cannibalism did not directly lead to development of resistance to kuru. Rather, this mutation was likely present in the population before the kuru epidemic, but it became much more common when it provided a genetic advantage — that is, people with the mutation were able to survive kuru. Such selection of genetic traits is the basis of evolution.

"This is a striking example of Darwinian evolution in humans, the epidemic of prion disease selecting a single genetic change that provided complete protection against an invariably fatal dementia," Dr. John Collinge, the senior author of the study and a professor of neurodegenerative disease at University College London, said in a statement.

The genetic mutation appears to prevent prion proteins from changing shape. Understanding exactly how the mutation does this could lead to new insights into how to prevent prion disease, the researchers said.

Follow Rachael Rettner @RachaelRettner. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Rachael is a Live Science contributor, and was a former channel editor and senior writer for Live Science between 2010 and 2022. She has a master's degree in journalism from New York University's Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program. She also holds a B.S. in molecular biology and an M.S. in biology from the University of California, San Diego. Her work has appeared in Scienceline, The Washington Post and Scientific American.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus