Viking DNA helps reveal when HIV-fighting gene mutation emerged: 9,000 years ago near the Black Sea

A study of more than 3,000 genomes has traced a gene mutation that confers HIV resistance to a person who lived near the Black Sea around 7000 B.C.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

A gene variant that helps protect people from HIV infection likely originated in people who lived during the span of time between the Stone Age and the Viking Age, a new study of thousands of genomes reveals.

"It turns out that the variant arose in one individual who lived in an area near the Black Sea between 6,700 and 9,000 years ago," Simon Rasmussen, a bioinformatics expert at the University of Copenhagen and co-senior author of the study, said in a statement. The variant must have been helpful for something else in the past, since HIV in humans is less than a century old.

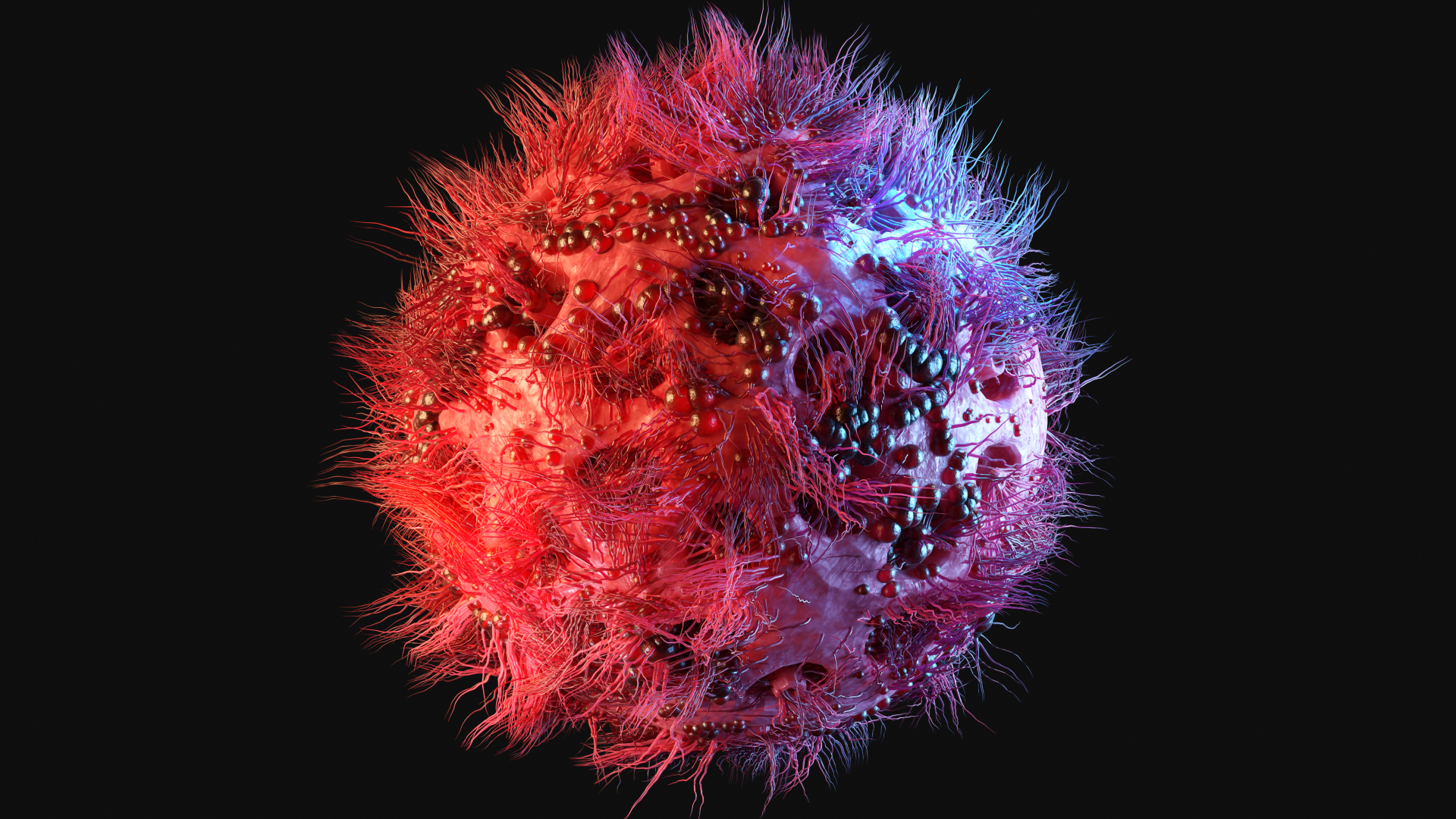

In a study published May 5 in the journal Cell, Rasmussen and his colleagues detailed their search for the origin of a genetic mutation known as CCR5 delta 32. CCR5 is a protein predominantly found in immune cells that many — but not all — HIV strains use to break into those cells and trigger infection.

But in people with two copies of the CCR5 delta 32 mutation, the protein gets disabled, essentially "locking out" the HIV virus. Scientists have taken advantage of this mutation to cure a handful of people of HIV.

Scientists have learned that this variant makes up 10% to 16% of CCR5 genes seen in European populations. However, attempts to identify its origin and trace its spread have previously come up short, since ancient genomes are often extremely fragmentary.

In the new study, the research team identified the mutation in 2,504 genomes from modern humans sampled for the 1000 Genomes Project, an international effort to catalog human genetic variation. Then, they created a model to search 934 ancient genomes from various regions of Eurasia ranging from the early Mesolithic period to the Viking Age, from roughly 8000 B.C. to A.D. 1000.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"By looking at this large dataset, we can determine where and when the mutation arose," study co-author Kirstine Ravn, a researcher at the University of Copenhagen, said in the statement.

The team's genetic detective work revealed that the person who first carried this mutation lived near the Black Sea around 7000 B.C., around the time early farmers arrived in Europe via Western Asia. The researchers also discovered that the prevalence of the mutation exploded between 8,000 and 2,000 years ago, suggesting it was extremely useful as people moved out of the Eurasian steppe.

The study's findings contradict previous assumptions that the mutation emerged more recently. For instance, this means that the increase in the frequency of the mutation did not result from medieval plagues or from Viking exploration, which may have introduced pressure for humans' immune cells to evolve.

When it's not being ransacked by HIV, the CCR5 protein helps control how immune cells respond to signals called chemokines, likely helping direct cells to sites of inflammation in the body.

The researchers suggest that people who carried the special CCR5 variant had an advantage. "People with this mutation were better at surviving, likely because it dampened the immune system during a time when humans were exposed to new pathogens," study co-author Leonardo Cobuccio, a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Copenhagen, said in the statement. While this sounds negative, an overly aggressive immune system can be deadly, he said — when facing new germs, you want just enough of an immune response to subdue the threat without hurting the body itself.

"As humans transitioned from hunger-gatherers to living closely together in agricultural societies," Cobuccio said, "the pressure from infectious diseases increased, and a more balanced immune system may have been advantageous." Of course, this is a hypothesis; the exact pressures that lead to the variant's increase aren't known for sure.

Stone Age quiz: What do you know about the Paleolithic, Mesolithic and Neolithic?

Kristina Killgrove is a staff writer at Live Science with a focus on archaeology and paleoanthropology news. Her articles have also appeared in venues such as Forbes, Smithsonian, and Mental Floss. Kristina holds a Ph.D. in biological anthropology and an M.A. in classical archaeology from the University of North Carolina, as well as a B.A. in Latin from the University of Virginia, and she was formerly a university professor and researcher. She has received awards from the Society for American Archaeology and the American Anthropological Association for her science writing.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus