Maya civilization had 16 million people at peak, new study finds — twice the population of modern-day NYC

After using lasers to map the Maya Lowlands, researchers have updated their estimates of the total Maya population during the Late Classic Period (A.D. 600 to 900).

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

The Maya population during the civilization's peak 1,400 years ago may have been far larger than previously thought, new research reveals. The study also hints that Maya settlements at that time were far more complex and interconnected than prior studies had suggested.

A 2018 study estimated there were 11 million Maya between A.D. 600 and 900, known as the Late Classic Period. But in new research published online July 7 in the Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports, some of the 2018 study's authors have revised the estimate to 16 million.

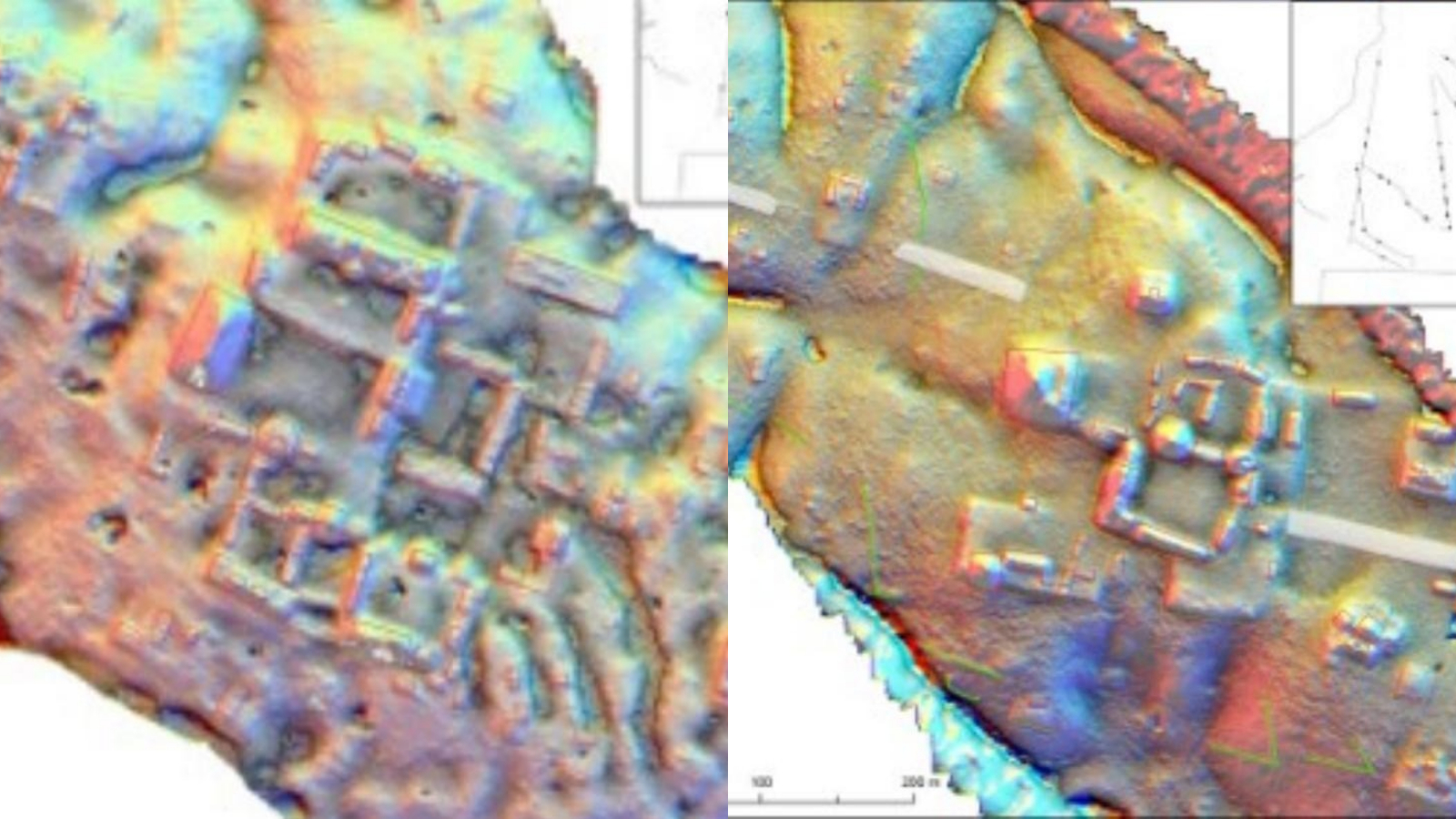

Both studies estimated the Maya population size using lidar (light detection and ranging) data, which is obtained with an aircraft carrying a machine that shoots laser pulses at the ground to create 3D maps of an area. The ruins of buildings on these maps can provide clues about population density, which researchers can extrapolate to come up with a total population count.

"We expected a modest increase in population estimates from our 2018 lidar analysis, but seeing a 45% jump was truly surprising," Francisco Estrada-Belli, a research professor in the Middle American Research Institute at Tulane University in Louisiana and the new study's lead author, said in a statement. "This new data confirms just how densely populated and socially organized the Maya Lowlands were at their peak."

The Maya Lowlands are swathes of forested land that include parts of modern-day Guatemala, Belize and Mexico. Specifically, the researchers created lidar maps for 36,700 square miles (95,000 square kilometers) of land in Guatemala's Petén department, western Belize, and the Mexican states of Campeche and Quintana Roo.

The Maya civilization peaked between A.D. 250 and 900, with numerous cities thriving in Mesoamerica during that time. Researchers have long thought that, aside from these cities, the civilization was limited to scattered settlements interspersed with farmland in the region's sprawling tropical rainforests.

Related: Genomes from ancient Maya people reveal collapse of population and civilization 1,200 years ago

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

However, the new research shows that Maya settlements were far more complex and interconnected than previously thought.

"We're confident these lidar-based findings give us the clearest picture yet of ancient Maya settlement patterns," Estrada-Belli said. "We now have hard evidence that Maya society was highly structured across both cities and rural areas and far more advanced in resource and social organization than previously understood."

The researchers found the same construction patterns across urban and rural areas, with a central public square controlled by the elite, and residential areas and agricultural fields distributed around these plazas. Almost all of the buildings revealed with lidar were located within 3 miles (5 km) of a plaza, suggesting that rural folk, who generally weren't elites, had access to most aspects of civic and religious life, according to the study.

The findings challenge the long-held assumption that rural Maya settlements were isolated from the cities and, therefore, disconnected from administrative and ceremonial centers. "No rural community could be regarded as isolated, disembedded or independent," the researchers wrote in the study.

The results also showed that the northern Maya Lowlands were more urbanized and densely populated than previously recognized, explaining the bump in the estimated population size.

"The northern Central Maya Lowlands were far from predominantly rural," the researchers wrote. "The relative proportions of urban to rural density zones [...] are remarkably similar between the southern and northern regions, challenging earlier assessments."

Still, the northern Maya Lowlands had extensive agricultural infrastructure, which was likely run by elites who managed food production and distribution, the researchers wrote.

The new population estimates raise new questions about the civilization's fall between A.D. 800 and 1000, because a bigger population may have exacerbated political turmoil and environmental problems, the team concluded in the study.

Today, many Maya continue to live in Mesoamerica, including about 8 million in southern Mexico and Central America, according to the MesoAmerican Research Center at the University of California, Santa Barbara.

Sascha is a U.K.-based staff writer at Live Science. She holds a bachelor’s degree in biology from the University of Southampton in England and a master’s degree in science communication from Imperial College London. Her work has appeared in The Guardian and the health website Zoe. Besides writing, she enjoys playing tennis, bread-making and browsing second-hand shops for hidden gems.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus