Lasers reveal Maya city, including thousands of structures, hidden in Mexico

The new city, dubbed Valeriana, was a dense urban settlement with temple pyramids and a ball court.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Laser surveys have revealed a massive centuries-old Maya city in Mexico's Yucatán Peninsula.

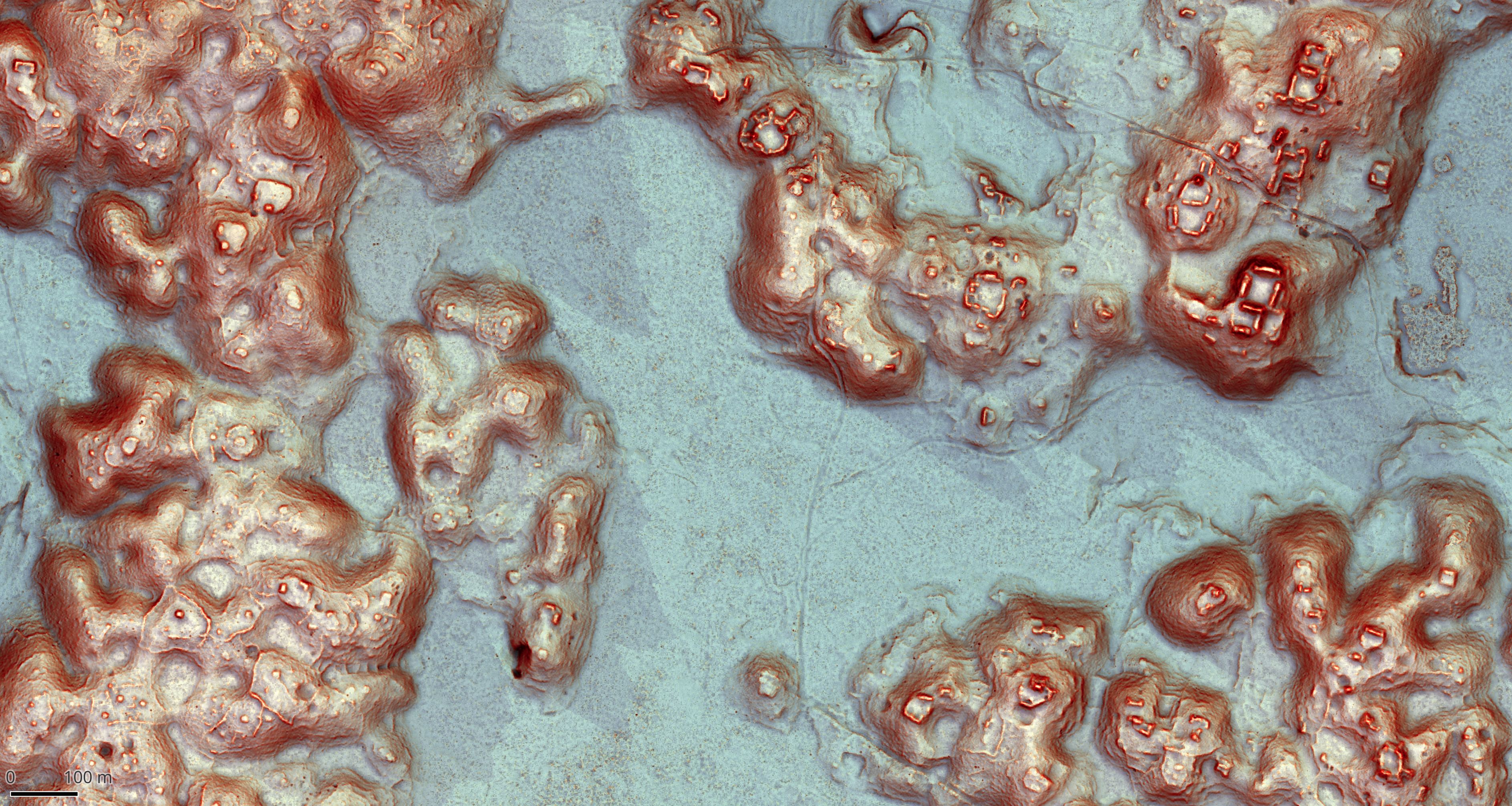

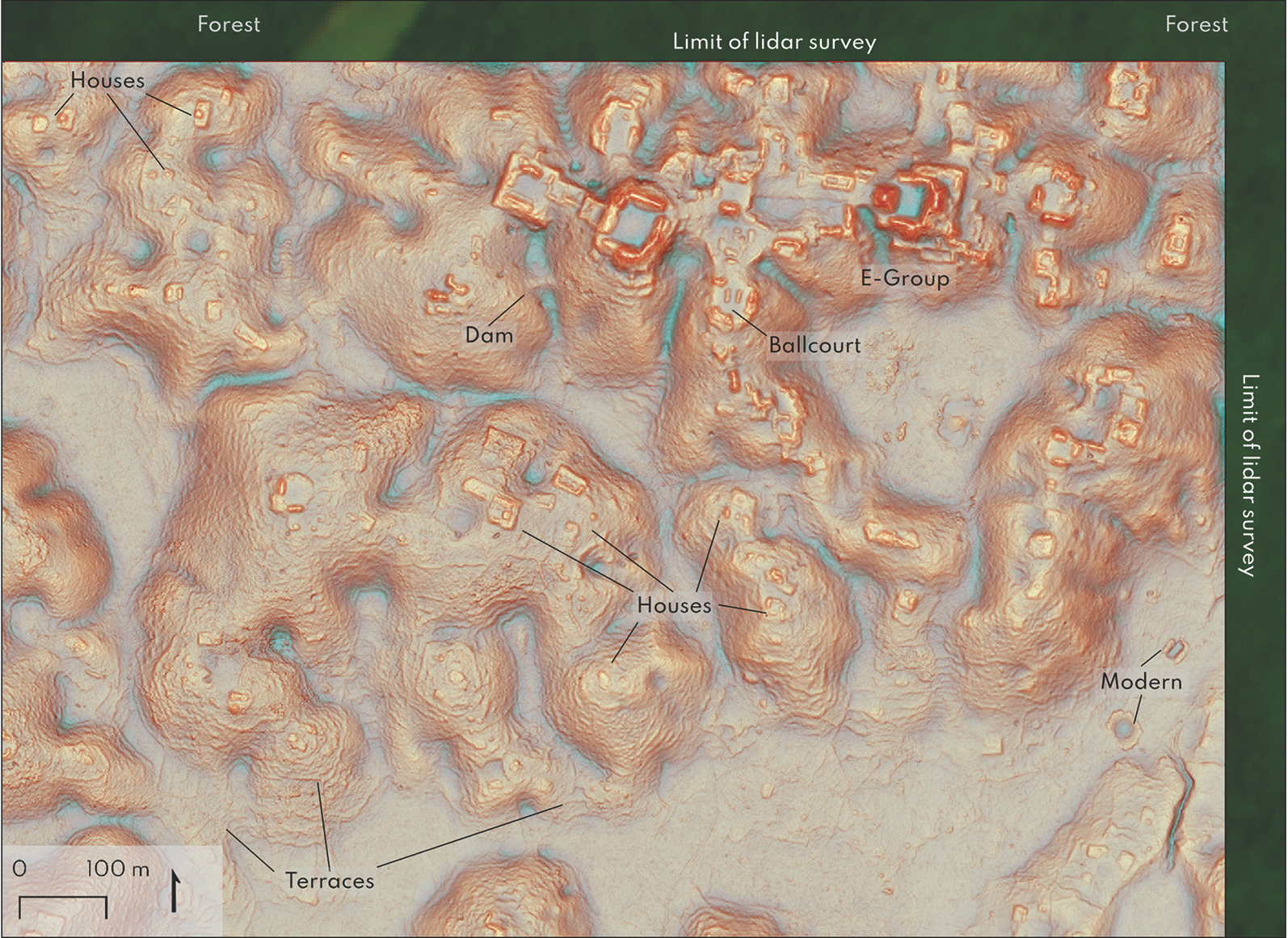

The city contains up to 6,674 structures, including pyramids like the ones at Chichén Itzá and Tikal, according to a study published Tuesday (Oct. 29) in the journal Antiquity. The researchers used previously created lidar (light detection and ranging) maps, which are created by shooting laser pulses at the ground, to reveal the potentially 1,500-year-old site.

With the rise of lidar technology over the past few decades, the discovery of ancient settlements has risen dramatically. However, this technology is expensive and often not accessible to early-career scientists like Luke Auld-Thomas, an archaeologist at Northern Arizona University and first author of the study. But the researchers had an idea of how to get around this barrier.

"Scientists in ecology, forestry and civil engineering have been using lidar surveys to study some of these areas for totally separate purposes," Auld-Thomas said in a statement. "So what if a lidar survey of this area already existed?"

Related: Lasers reveal massive, 650-square-mile Maya site hidden beneath Guatemalan rainforest

By combing through previously commissioned lidar studies, Auld-Thomas located a survey created to measure and monitor carbon in forests in Mexico. By analyzing 50 square miles (129 square kilometers) in east-central Campeche, Mexico, that had never been searched for Maya structures before, Auld-Thomas and his colleagues found hidden imprints of a Maya city tucked within modern farms and highways.

The city, which the researchers named Valeriana after a nearby freshwater lagoon, dates to the Classic period (A.D. 250 to 900), and shows "all the hallmarks of a Classic Maya political capital," including multiple enclosed plazas connected by a broad causeway, temple pyramids, and a ball court, the researchers noted. Farther from the Valeriana city center, terraces and houses dot the hillside, suggesting a dense urban sprawl. This study is the first to reveal Maya structures in east-central Campeche.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"The government never knew about it; the scientific community never knew about it," Auld-Thomas said. "That really puts an exclamation point behind the statement that, no, we have not found everything, and yes, there's a lot more to be discovered."

"Unfailingly, everywhere that this sort of work is done, there's more settlement [discovered]," Thomas Garrison, an archaeologist at the University of Texas at Austin who was not involved in the study, told Live Science. "It all provides more pieces for this huge puzzle, and every puzzle piece counts." The next step in the research is for archaeologists to confirm the city on-site, Garrison added.

As the diversity and density of the Maya civilization is slowly revealed, study of this time period becomes even more important, Auld-Thomas noted.

"Given the environmental and social challenges we're facing from rapid population growth, it can only help to study ancient cities and expand our view of what urban living can look like," Auld-Thomas said. "Having a larger sample of the human career, a longer record of the accumulated residue of people's lives, could give us the latitude to imagine better and more sustainable ways of being urban now and in the future."

Sierra Bouchér is a Washington, D.C.-based journalist whose work has been featured in Science, Scientific American, Mongabay and more. They have a master's degree in science communication from U.C. Santa Cruz, and a research background in animal behavior and historical ecology.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus