Massive 3,000-year-old Maya site in Mexico depicts the cosmos and the 'order of the universe,' study claims

A roughly 3,000-year-old site in Mexico was built in the shape of a cosmogram that stretches for miles, a new study suggests.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

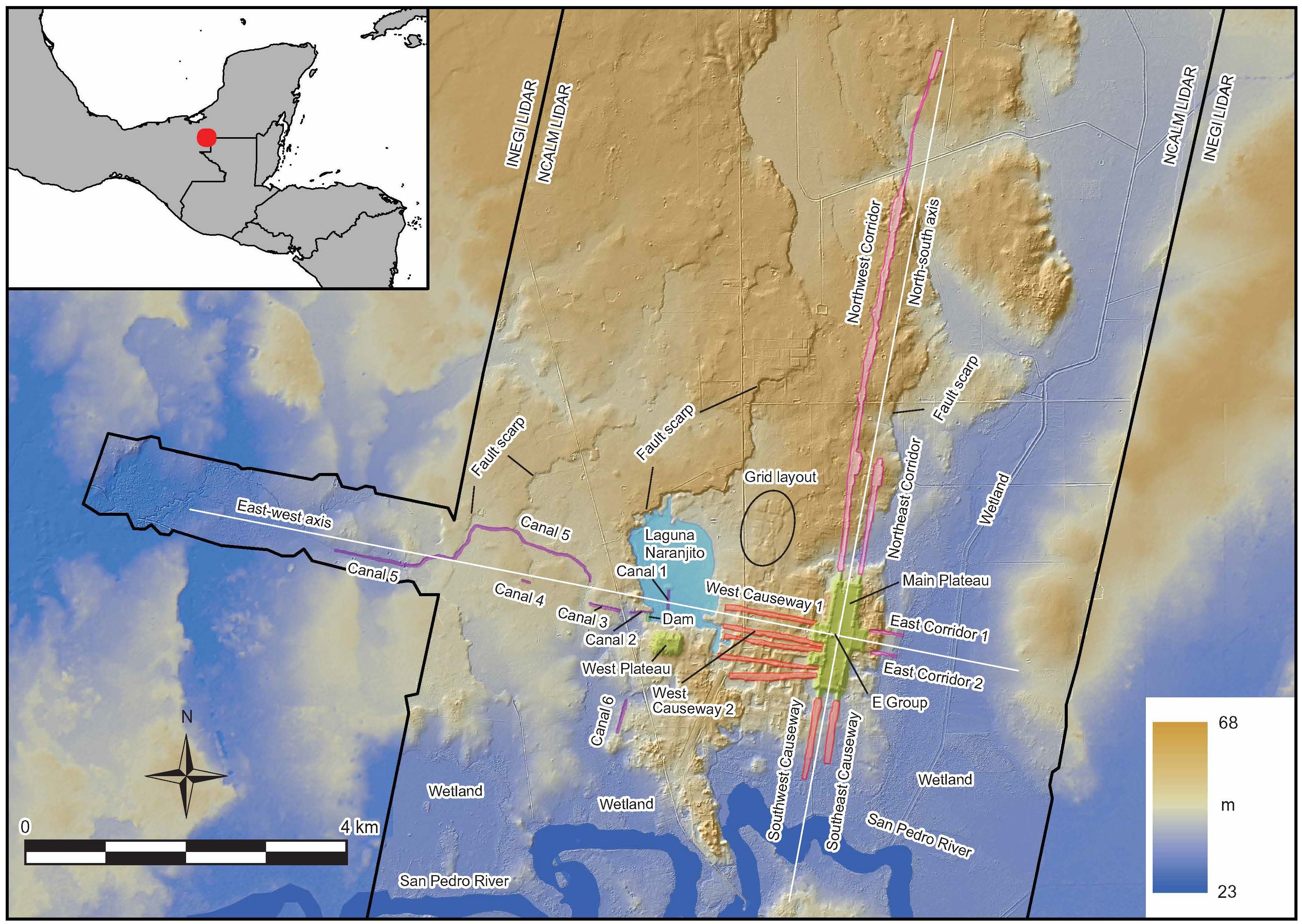

A 3,000-year-old Maya site is actually a giant, city-size map depicting the "order of the universe," researchers say. The ruin, in what is now southeastern Mexico, was a cosmogram — a representation of how ancient people at the site viewed the cosmos, a new study suggests.

The site, known as Aguada Fénix, is the "oldest and largest monumental architecture in the Maya area" and is larger than many ancient cities in Mesoamerica, the researchers wrote in the study. Although its construction was a major endeavor, its cultural significance, likely motivated people to help construct it, meaning its builders were probably not coerced into labor, the researchers suggested.

In effect, building Aguada Fénix may have been a celebrated communal activity for ancient people, just like Stonehenge likely was in prehistoric England.

"Large construction events and collective rituals may also have involved feasting, the exchange of goods among different groups, and opportunities to meet mates, which probably provided additional incentives for people to gather," the authors wrote in the new study, which was published Wednesday (Nov. 5) in the journal Science Advances.

Aguada Fénix dates to 1050 B.C., before the Maya's writing system was invented, so there are no written records of the site. It was abandoned around 700 B.C. Scientists investigated it between 2020 and 2024 to learn more about the site. They not only excavated Aguada Fénix but also used lidar (light detection and ranging), a technique in which lasers are pulsed out from an aircraft, and the reflected light is then measured and used to create imagery of the landscape.

Their analysis showed that the cosmogram was created using a system of structures that include canals, causeways and a dam. These structures crisscross each other to create a series of cross shapes. The size of the cosmogram, which measures 5.6 by 4.7 miles (9 by 7.5 kilometers), "is comparable to, or even greater than, those of later Mesoamerican cities," including Tikal and Teotihuacan, the team wrote in their paper.

At the center of the structure is a series of small buildings and platforms, which archaeologists call "E group." It has several buried deposits that contained objects that likely had a ceremonial meaning, including greenstone ornaments that may represent a crocodile, a bird and possibly a female giving birth; ceramic vessels; and pigments.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

While a small lake provided water for the canals, the archaeologists noted that the sheer size of the cosmogram, and the small size of the lake, would have prevented its canals from being filled with water for lengthy periods. They also said there are no signs of agricultural irrigation, suggesting that the canals were not used to grow crops.

The cosmogram was ultimately unfinished when the site was abandoned in 700 B.C., and some of the canals were never completed, the team wrote.

The researchers noted they did not find any signs of social hierarchy at Aguada Fénix — unlike at other, later Maya sites such as Tikal in Guatemala and Copan in Honduras that have evidence of the Maya's strict social structure. The team estimated that more than 1,000 people were needed to build Aguada Fénix. Perhaps "leading figures, who had specialized skills and knowledge of astronomical observations and calendrical calculations" designed the large cosmogram, the authors wrote.

Understanding the meaning

Understanding the full meaning of the cosmogram is difficult given that there are no written records that date to this time, but study lead researcher Takeshi Inomata, a professor of archaeology at the University of Arizona who specializes in the Maya, said that the movement of the sun was reflected in its design.

The people who used the site "probably thought the universe is ordered according to the north-south and east-west axes," Inomata told Live Science in an email. The east-west axis "was tied to the movement of the sun and was probably related to the passage of time as well," he said.

Additionally, the builders "aligned Aguada Fenix to a specific direction of the sunrise, which were associated with the cycle of 260 days, which became the most important ritual calendar cycle for the later Maya and Aztec," he said. "So they probably thought the orders of space and time were tied together."

Scholars react

Scholars not involved with the research had mixed reactions to the team's findings. Michael Smith, a professor of archaeology at Arizona State University, told Live Science in an email that this "is a fascinating and important site, but the authors have not demonstrated that the site was a 'cosmogram.'" He said that the team needs to define what exactly they consider to be a cosmogram and develop a clear method to identify one.

Other scholars were more supportive of the findings. David Stuart, a professor of Mesoamerican art and writing at the University of Texas at Austin, told Live Science in an email that "I see this as an important discovery, with a very careful and meticulous analysis by Takeshi and his team."

Arlen Chase, an anthropologist and the chair of the Department of Comparative Cultural Studies at the University of Houston, was also supportive of the team's findings, noting that the deposits found in the E group support the team's ideas. The deposits were in the center of the settlement and tended to be placed in cross shaped patterns, mimicking the site layout.

Ed Barnhart, director of the Maya Exploration Center, told Live Science in an email that "This report is very exciting!" and noted that "both the cosmogram and the canal systems are among the earliest ever found in Mesoamerica."

James Aimers, a professor of anthropology at the State University of New York at Geneseo, said that whether this could be considered a cosmogram depends on how you define it. "For me, the most important claim in the article is that all this monumentality was built collectively rather than under the direction of powerful rulers," Aimers told Live Science in an email. "This is in line with a lot of new interpretations that stress collective action rather than hierarchy in Mesoamerica."

Ancient Maya quiz: What do you know about the civilization that built pyramids across Mesoamerica?

Owen Jarus is a regular contributor to Live Science who writes about archaeology and humans' past. He has also written for The Independent (UK), The Canadian Press (CP) and The Associated Press (AP), among others. Owen has a bachelor of arts degree from the University of Toronto and a journalism degree from Ryerson University.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus