200-foot scorpion effigy mound in Mexico may align with the solstices

A 205-foot-long, scorpion-shaped mound in Mexico likely helped Mesoamericans mark the summer and winter solstices, a new study finds.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

A gigantic scorpion-shaped mound built centuries ago in Mexico may align with the winter and summer solstices, a new study finds.

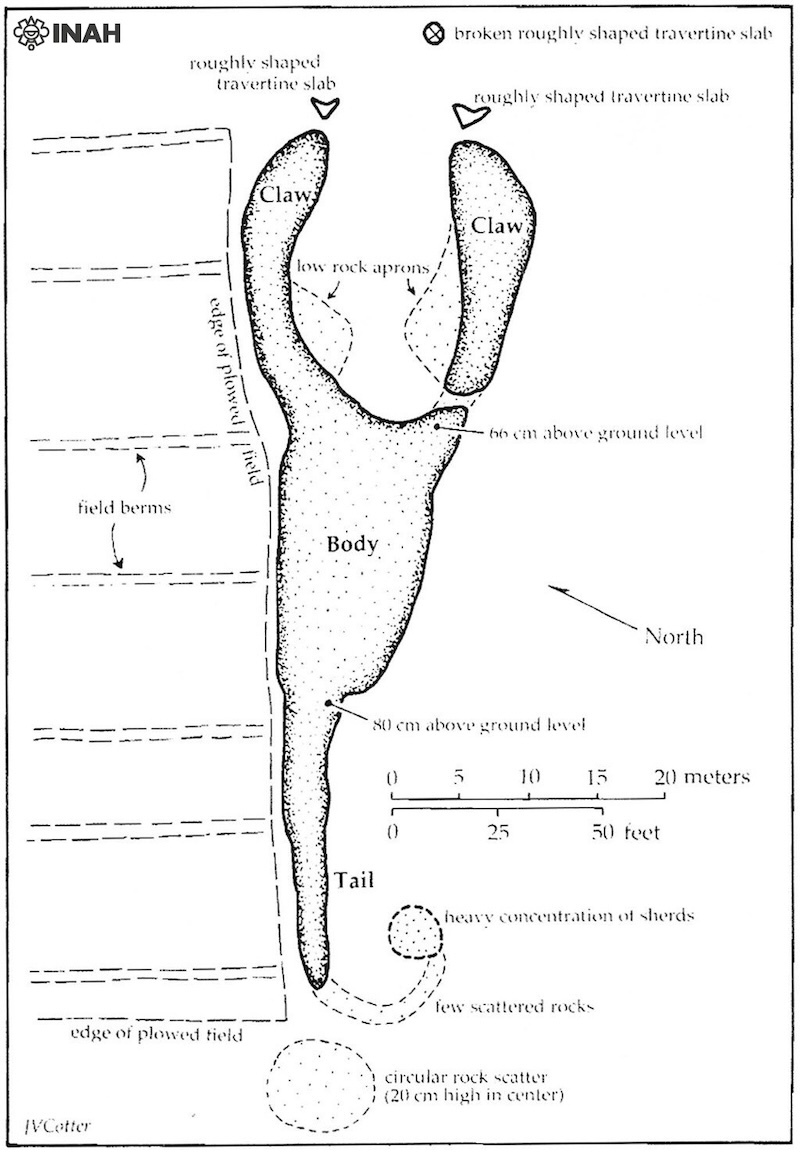

Archaeologists documented the 205-foot-long (62.5 meter) mound in 2014 while surveying prehistoric irrigation systems in Tehuacán Valley, about 160 miles (260 kilometers) southeast of Mexico City. Several artifacts and offerings were found at the scorpion mound, which helped the team date it to the Late Classic and Early Postclassic periods (circa A.D. 600 to 1100).

The scorpion effigy mound has remained remarkably intact over the centuries. It has a head, body, pincers and tail sculpted with a mix of dirt and rocks that are piled up to 31 inches (80 centimeters) high. The team found buried artifacts where the "stinger" would have been.

"This sort of effigy feature is quite unusual in Mesoamerica," the researchers wrote in the study, which was published Aug. 29 in the journal Ancient Mesoamerica.

The discovery also suggests that regular Mesoamericans, not just the elite, were looking to the sky and monitoring astronomical events, said study first author James Neely, a professor emeritus of archaeology at the University of Texas at Austin.

"It is the first indication that knowledge and control of astronomical phenomena based on solar observations was not totally in control of the elite class," Neely told Live Science in an email.

Astronomical observatory

The scorpion is one of 12 mounds, which appear to be part of a civic and ceremonial complex that spans about 22 acres (9 hectares) and includes what may be a looted burial or storage pit. This complex may have been used for astronomical observation, helping agricultural workers know when to perform rituals and plant and harvest their crops, the team said.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Some of the mounds have rooms and walls, but only the scorpion has a specific shape, making it an effigy mound — or piled dirt that is purposefully formed into a specific shape, symbol or figure. While thousands of earthen mounds built by Indigenous Americans are found in North America, effigy mounds are "notably sparce" in Mesoamerica, making the scorpion one a rare find.

The scorpion, known as Tlāhuizcalpantēcuhtli, was a powerful deity in pre-Hispanic Mesoamerica. Many Mesoamerican peoples saw it as a celestial deity and a prominent figure in the Aztec pantheon of gods. To Mesoamericans, Tlāhuizcalpantēcuhtli represented Venus, the morning star planet, the researchers wrote in the study.

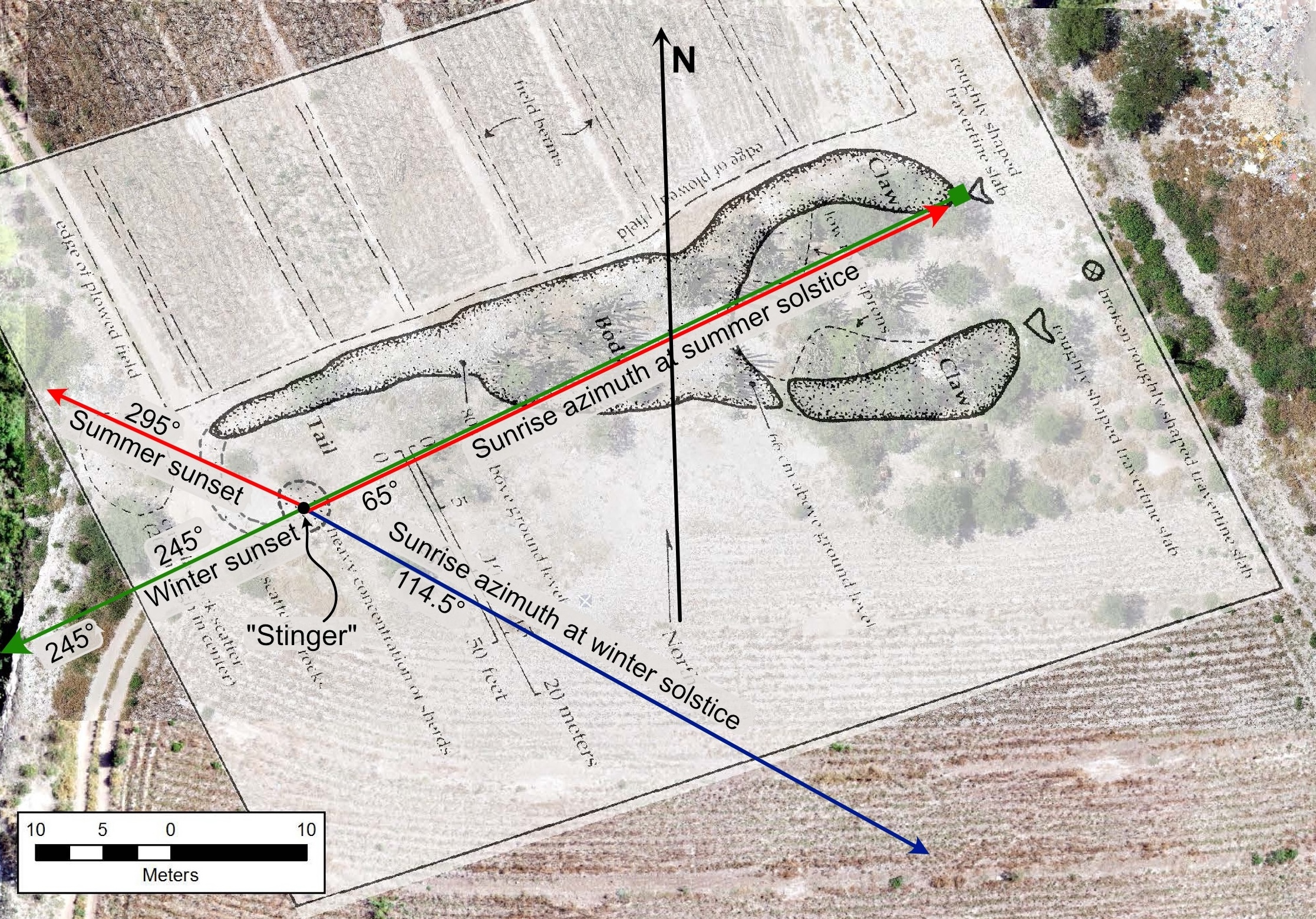

While studying the scorpion effigy mound, the team noticed that it was oriented east-northeast, a clue that it aligns with sunrise on the summer solstice, they wrote in the paper. To investigate, the researchers calculated the sun’s trajectory on both the summer and winter solstices.

"We estimate that on the morning of the summer solstice, if a person sighted from the 'stinger' (the circular ceramic cluster at the presumed end of the scorpion’s tail), the sun would rise above the tip of the northern (left) claw," they wrote in the study.

Some of the centuries-old pottery that archaeologists found at the scorpion effigy mound.

Archaeologists found a molcajete offering at the scorpion effigy mound. We see (left) the way the artifact was found and (right), the artifact with the cover bowl taken off.

The summer solstice was an important ceremonial date in Mesoamerica, as it kicked off the beginning of the rainy and planting season, the researchers noted.

"For the days leading up to the solstice, the sun would rise between the two claws, and thereby signal the approach of the rainy season so the local farmers could prepare their fields for planting," the researchers added.

Likewise, the sunset on the winter solstice also connected with the scorpion effigy mound. If a person stood at the tip of the left claw, they could see the setting sun beyond the stinger, the team found.

"Based on these estimates, the [scorpion] mound would allow its users to identify the dates of both the summer and winter solstices, common alignments for Mesoamerican architecture," the researchers wrote in the study.

Among the artifacts found at the scorpion effigy mound were bowls, jars and plate fragments. The archaeologists also found molcajetes — tripod bowls that were used for grinding food — as well as an incense burner and the fragment of a hollow figurine that was likely involved in a ritual, they wrote.

The discovery of the mounds and astronomical observatory among the irrigation canals shows the complexity of the Mesoamerican civilization that built them, Neely said, adding that "this points to the prehistoric campesinos [countryside farmers] having lived a life way of greater independence and self-determination from elite/state control as do their modern counterparts."

Laura is the managing editor at Live Science. She also runs the archaeology section and the Life's Little Mysteries series. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus