Canyon de Chelly: Photos of Arizona's Geological Beauty

Breathtaking vista

Canyon de Chelly (pronounced "de-shay") National Monument is one of the many rugged yet beautiful canyons that are commonly found in the southwestern region of the United States.

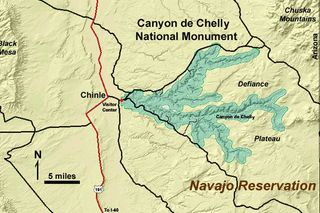

Located on the Colorado Plateau in the far northeastern part of Arizona, near the small town of Chinle, Canyon de Chelly was called "Tsegi" ("say-ee"), which means "rock canyon" or "among the rocks," according to the local Navajo people. When the Spanish conquistadors arrived in the 17th Century, they corrupted the Navajo name to "de Chelly" ("de-shay-yee").

Where the streams meet

Canyon de Chelly is actually composed of four separate canyons: del Muerto to the north, de Chelly in the center, and Black Rock and Monument to the south. The total length of the four canyons is over 100 miles (161 kilometers).

The canyons were all carved by the seasonal flow of water rushing down three high desert streams: the Rio de Chelly, Whiskey and Tsaile Creeks. These streams, which often run dry within the canyon walls, originate high in the Chuska Mountains to the northeast and come together in Canyon de Chelly to form the Chinle Wash.

Ancient rocks

The shallowest area of Canyon de Chelly is found at the far western edge, where the canyon walls rise only 30 feet (9 meters) above the Chinle Wash. In the southeastern part of the canyon, the walls rise over 1,100 feet (335 m) above the canyon floor. Within those canyon walls, more than 11 million years of geological history is revealed. The rock walls vary from red granites and quartzite to sandstone and conglomerates.

Making mountains

The formation of Canyon de Chelly is the direct result of the geophysical force of a regional uplift, known here as the Defiance Uplift, which occurred during the Laramide orogeny, a period of intense mountain-building. This orogeny began roughly 70 million years ago and was a time of major tectonic events in the western region of North America.

Layers of rocks

As a result of these ancient uplifting forces, the land rose above the ancient regional seas. In the Canyon de Chelly region, rocks from the Permian Period and Paleozoic Era ended up resting on top of Precambrian rocks. The Canyon de Chelly region became an uplifted island in the middle of an already uplifted Colorado Plateau.

Washed away

The major force of erosion that resulted in the formation of Canyon de Chelly was that of running water. The Rio de Chelly, along with Whiskey and Tsaile Creeks, cut and shaped the four canyons’ unique and beautiful features. Over the years, the upper level of rocks have eroded away, leaving the older rock layers seen today, most notably the so-called Chelly Sandstone.

Rock patterns

The Chelly Sandstone is an ideal example of wind-blown dune deposits. In this canyon, dune sediments were laid down roughly 90 to 250 million years ago, during the Permian Period. Chelly Sandstone is known for its windblown and cross-bedded layers that are highly inclined to the horizontal. This type of sandstone is known for its swirling contours that create the appearance of a petrified desert landscape.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Dune erosion

During the Mesozoic Era, some 210 to 230 million years ago, a harder and more resistant material, called Shinarump Conglomerate, was laid down upon the ancient dunes. This conglomerate layer, when exposed for many millennia of wind and rain, results in the formation of countless shallow potholes within the canyon walls.

Living walls

A thin layer of desert varnish is found on many of the canyon walls. Manganese-fixing bacteria that live on the moist cracks and crevasses of the sandstone add an element of ruggedness and attractiveness to the red walls, creating these sweeping, black-shiny streaks.

Among the ruins

There are over 2,700 archeological sites found within Canyon de Chelly. Evidence suggests that humans have occupied these lands for over 1,500 years. Ruins of a people known as the Anasazi are found throughout the canyons.

The Anasazi ruins shown here are known as "White House Ruins." The name Anasazi comes from the Navajo language and, when translated, means “enemy ancestors." The Navajo people, who call themselves the “Dine," are thought to have arrived in this high desert land less than a century before to the arrival of the Spanish. Today, Canyon de Chelly is a national monument and part of the Navajo Nation.

Canyon plants

The land of Canyon de Chelly is within the so-called Transition Life Zone, which ranges from desert grassland to evergreen forests in the Chuska Mountains. At an elevation that ranges from 5,000 to 6,000 feet (1,524 to 1,829 m), the land receives less than 10 inches (25 centimeters) of rain each year.

Opuntia cacti and a variety of yucca and other high desert plants are commonly found in the region, in addition to the hardy grama grass. Stands of Utah juniper, Juniperus osteosperma, dot the landscape, providing an abundance of pinon nuts for both human and animal consumption.