Kilimanjaro's Shrinking Glaciers Could Vanish by 2030

SAN FRANCISCO — Kilimanjaro's shrinking northern glaciers, thought to be 10,000 years old, could disappear by 2030, researchers said here yesterday (Dec. 12) at the annual meeting of the American Geophysical Union.

The entire northern ice field, which holds most of Kilimanjaro's remaining glacial ice, lost more than 140 million cubic feet (4 million cubic meters) of ice in the past 13 years, said Pascal Sirguey, a research scientist at the University of Otago in New Zealand. That's a cube measuring roughly 520 feet (158 m) on each side.

The loss in volume is approximately 29 percent since 2000, while the total surface area lost is 32 percent, Sirguey said. Last year, the ice field split in two, revealing ancient lava that may not have seen the sun for millennia. [Video: Kilimanjaro's Shrinking Glaciers]

It also turns out the glaciers aren't shrinking at the same pace. Credner Glacier, which may get more sun in its northwestern spot, accounts for nearly half (43 percent) of the past decade's lost ice, the researchers found.

If Kilimanjaro's northern glaciers continue to shrivel as fast as they did in the past 12 years, the Credner will completely vanish by 2030, Sirguey said. The rest of the ice will last another 30 years from today, he added. About 700 million cubic feet (20 million cubic m) of ice remains in the northern glaciers — 71 percent of it in Drygalski and Great Penck Glaciers.

"This projection confirms the disappearance of the northern ice field by the mid-21st century," Sirguey said.

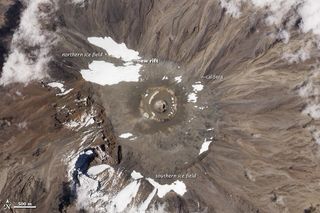

Sirguey and his colleagues tracked the ongoing changes atop Kilimanjaro, Africa's tallest peak, with a detailed digital elevation model developed from GeoEye-1 satellite images. Their new 3D view of the massive volcano is the best in decades, and will eventually help create new topographic maps for the thousands of tourists who attempt to hike the 19,341-foot (5,895 m) mountain every year, Sirguey said. The new model can highlight topographic features such as glaciers and volcanic craters at a 20-inch (50 centimeters) resolution.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"We are working with the Tanzanian government to publish our new digital elevation model," Sirguey told LiveScience. "I think there will be a lot of tourist interest, because right now, the maps are based on the last elevation survey from 1962."

The research team also plans to use the model to better understand the reasons for the shrinking ice. Less snowfall could play a role, as could global warming.

Email Becky Oskin or follow her @beckyoskin. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on LiveScience.

Most Popular