Muppet-Faced Fish Swam Alongside Dinosaurs

A Muppet-faced fish with a lanky body more than 6 feet long gulped down plankton in Earth's ancient oceans about 92 million years ago, a new study finds.

Researchers identified two new species of the enormous fish, which lived during the Cretaceous period, when dinosaurs roamed the world. But like many of its contemporaries, the fish went extinct after an asteroid struck the Yucatan Peninsula about 66 million years ago.

Until now, scientists had only identified one species of this fish, which belongs to the genus Rhinconichthys (rink-oh-NEEK-thees). The new study builds on that count, and shows that these fish lived all over the world, the researchers said. [Image Gallery: Ancient Monsters of the Sea]

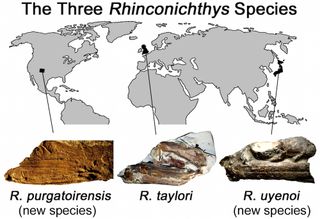

"Based on our new study, we now have three different species of Rhinconichthys from three separate regions of the globe, each represented by a single skull," study co-researcher Kenshu Shimada, a paleobiologist at DePaul University in Chicago, said in a statement. "This tells just how little we still know about the biodiversity of organisms through the Earth's history. It's really mind-boggling."

Shimada first encountered a Rhinconichthys fossil about 30 years ago in the office of his mentor, Teruya Uyeno, a curator emeritus of the National Museum of Science and Nature in Japan. Later, in 2010, Shimada and his colleagues uncovered another Rhinconichthys in England, which they named R. taylori.

"We had no idea back then that the genus was so diverse and so globally distributed," Shimada said.

In 2012, researchers unearthed a new specimen in southeastern Colorado, named R. purgatoirensis for the rugged Purgatoire River valley where it was found, Shimada said. It took excavators more than 150 hours to remove the ancient skull from the surrounding rocks, he added.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

In the new study, the researchers described the Colorado specimen and reanalyzed the fish fossil from Hokkaido, Japan, which they called R. uyenoi in honor of Shimada's mentor. The new analyses helped them learn more about ancient sea life, the researchers said.

Rhinconichthys is part of a family called the pachycormids, which includes the largest known bony fishes to live on Earth. Species in this fish family don't have any living descendants, but they lived large during their day. For example, all of the known species of Rhinconichthys had a skinny body, and measured at least 6.5 feet (2 meters) long, including its immense 1.5-foot-long (0.5 m) head.

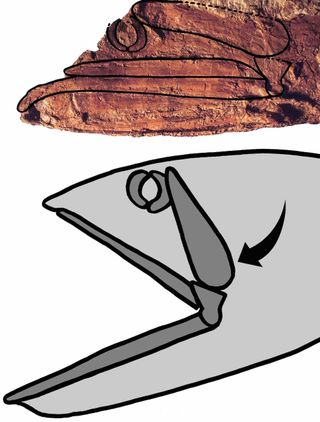

Moreover, Rhinconichthys' long head housed a large jaw that gaped open like a Muppet's mouth, Shimada said. One pair of bones, called the hyomandibulae, formed a large, oar-shaped lever that helped the jaws protrude and swing open, helping the fish fill its mouth with tasty plankton, he said.

"These pachycormids really cornered the market on industrial-scale plankton consumption during the age of the dinosaurs," Shimada said. "The fish had a highly expandable mouth that perhaps looked like a 'tube' about 1 foot [0.3 m] in diameter to take in a large amount of water to filter feed plankton using its gill apparatus."

This "planktivorous" diet, also known as suspension feeding, is still used by marine vertebrates today, including the blue whale, manta ray and whale shark. Thanks to the Rhinconichthys findings, researchers know that animals also used this method during the Mesozoic era, when the dinosaurs were alive.

"We have just barely scratched the surface of what was likely a complex ecosystem that existed in oceans during the age of the dinosaurs," Shimada said.

The study was published online Jan. 28 in the journal Cretaceous Research.

Follow Laura Geggel on Twitter @LauraGeggel. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Laura is the archaeology and Life's Little Mysteries editor at Live Science. She also reports on general science, including paleontology. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.

Most Popular