Antarctic Explorer Shackleton Hindered by Heart Defect, Docs Say

It's been a century since Sir Ernest Shackleton led some of the first major expeditions to Antarctica, but today, medical sleuths suggest Shackleton might have had a hole in his heart, possibly explaining the health problems he had all his life.

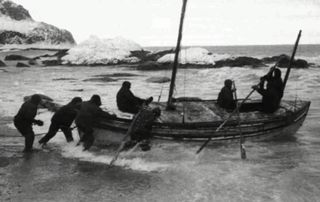

A famed explorer, Shackleton led the Nimrod Expedition of 1907 to 1909, members of which were the first people to climb Mount Erebus in Antarctica, the southernmost active volcano on Earth. But the adventurer is best known for leading the Endurance expedition 100 years ago, when his ship Endurance, the strongest vessel of its time, was crushed by sea ice off the coast of Antarctica.

Although Shackleton and his crew faced near death, they all succeeded in returning home.

The Endurance expedition was the third of four Antarctic expeditions that Shackleton undertook. It was also the only one during which he did not suffer a physical breakdown, according to a new paper by two doctors, retired anesthetist Ian Calder in London, and cardiologist Jan Till, of the Royal Brompton Hospital in London. [Antarctica: 100 Years of Exploration (Infographic)]

Shackleton was capable of great acts of endurance — for instance, he made the first crossing of the mountains and glaciers of South Georgia without any health issues. However, during other expeditions, Shackleton alarmed his companions with repeated attacks of breathlessness and weakness, Calder and Till wrote in their study.

Now, Calder and Till suggest that Shackleton's breakdowns were because of a hole in his heart. They detailed their findings Jan. 13 in the Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine.

Calder began investigating Shackleton after his own experience crossing South Georgia, a remote island in the Southern Ocean.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"I have always been interested in the 'heroic age' of Antarctica, the space exploration of its day," Calder told Live Science. "South Georgia is still a formidable challenge — it is so isolated, and the weather so severe. It made me more interested in Shackleton's life and death."

In the new research, he and Till analyzed records held in the Scott Polar Research Institute in Cambridge, England. Diary entries made by Dr. Eric Marshall, the medical officer on the Nimrod Expedition, revealed that Shackleton had a heart murmur on two occasions, the researchers found.

For instance, in an entry made on Beardmore Glacier dated Jan. 21, 1909, Marshall wrote, "[Shackleton] very unwell, walked by the sledge all day – Midday-Pulse on march thin & thready, irregular about 120." However, Shackleton recovered within a few days, and was one of the strongest members of the party by the end of the journey, marching for 30 miles to prevent the Nimrod from leaving without them.

Based on Shackleton's history of attacks of breathlessness, weakness and color change, and Marshall's findings of a heart murmur and an irregular pulse, the researchers diagnosed Shackleton with a congenital atrial septal defect, or hole in his heart. Shackleton died at age 47 after arriving in South Georgia at the beginning of his fourth expedition, probably due to heart problems exacerbated by his smoking.

The researchers suggested that Shackleton knew that he had something wrong with his heart — his father was a doctor, and Shackleton often avoided being examined by doctors who might have tried to prevent him from going to Antarctica.

"We feel sure that he knew there was an issue with his heart, but at that time there was no way of finding out what it actually was — no EKGs, no ultrasound, no scans and so on — and absolutely no treatment even if the problem had been identified," Calder said. "His collapses were infrequent, and the alternative was to revert to the mundane, by comparison, life of a seaman."

Today, about 2,000 babies are born yearly in the United States with an atrial septal defect, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The hole in the heart's wall sometimes closes on its own. But doctors can also do surgery to repair the hole, or give medications to help treat the symptoms.

"Some may feel that Sir Ernest was irresponsible in undertaking the leadership of Antarctic expeditions if he suspected a problem," Calder said in the study. "But to paraphrase Dr. Johnson, there is seldom a shortage of prudent people, whilst the great things are done by those who are prepared to take a risk. Few would deny that the quality of Shackleton's leadership during his third expedition 100 years ago was crucial to the survival of the party and remains an inspiration and example for generations to come."

Follow Charles Q. Choi on Twitter @cqchoi. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.