Retinal Prosthesis Could Help The Blind See

A retinal implant has given a brief glimpse of light to a small number of blind people, and could one day be a common treatment for vision loss due to injury or disease.

Shawn Kelly, a senior systems scientist at Carnegie Mellon University, has developed a computer chip that translates camera images into electrical pulses that the nerves inside the brain can understand. The result is vision.

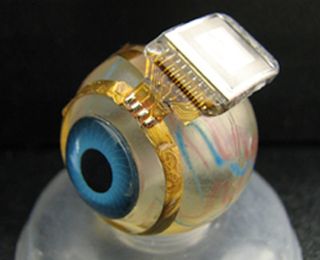

The cameras are incredibly small and mounted to a pair of glasses. The digital information picked up from the camera is sent along a wire to a thin film surgically implanted in the back of the patient's eye, between the sclera and the retina. The electrical signals stimulate the nerves in the retina, and that allows the patient to see. The system is powered via induction -- not much current is necessary since the electric field doesn't have to penetrate far into the head.

It's a far cry from the bionic eyes of science fiction, though. The resolution is only 256 pixels total, because that's how many electrodes can be made to fit on the back of the film. A typical digital camera has resolutions measured in millions of pixels and ordinary human vision involves approximately 1 million nerves, and more than 100 millon rod and cone cells. But it is something.

"At 256 we start to get some function back to people," Kelly told Discovery News. He said people who tested the system reported the ability to see some shapes and light and dark regions. The tests were not "field tests" in real-world conditions, but situations where the implant was used for a few hours and then removed.

There have been other proposals for retinal implants. Recent work in Britain used a self-powered retinal implant that is powered by light that enters the eye rather than the external glasses. At the Uniersity of Tubingen in Germany, another project involves an implant that has a 1,500 pixel resolution that is inserted on the front of the retina. That too, requires a pair of glasses.

Kelly said the difference with his design is that the processor is sealed well enough that no water vapor gets inside. Ordinarily the liquids in the eye (and the body generally) are in chemical equilibrium, but any implanted device with wires has spaces in it that can allow small amounts of vapor to form, which can reduce the implant's effectiveness." We have more intelligence in the eye," Kelly said. "Ours is designed to be stable long term."

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

One kind of blindness that will be targeted with this device is retinitis pigmentosa, a hereditary disease that destroys the cells in the eye that recieve light. Military veterans could also be helped. (Kelly recently recieved a $1.1 million grant from the Department of Veterans' affairs). Some veterans of World War II and Korea suffer from age-related macular degeneration. Others had their eyes damaged by laser rangefinders, Kelly said. The lasers (which are far more powerful than barcode scanners or CD players) can injure the eyes in a way that causes damage later in life.

This story was provided by Discovery News.

Most Popular