Did Human Ancestor 'Lucy' Have a Midwife?

How might the ancient relative of humanity dubbed "Lucy" have given birth? In a manner in between that of chimpanzees and humans, with newborns undergoing a bit of tilting in the birth canal as they were born, a new study finds.

Lucy and other members of her species may also have relied on midwives, researchers said.

These findings could shed light on how modern human childbirth evolved and made way for large brains, scientists added. [Photos: Mysterious Human Ancestor May Have Walked Alongside Lucy]

Modern humans give birth in a way quite different from how their primate relatives do it, according to research described in the book "Human Birth: An Evolutionary Perspective" (1987, Aldine Transaction) by Wanda Trevathan. This is likely because of both the unusually large size of the modern human brain and the way a woman's pelvis is positioned for upright walking, Trevathan wrote. Understanding the way in which human childbirth evolved could also shed light on how unique human traits such as large brains and upright postures emerged over time.

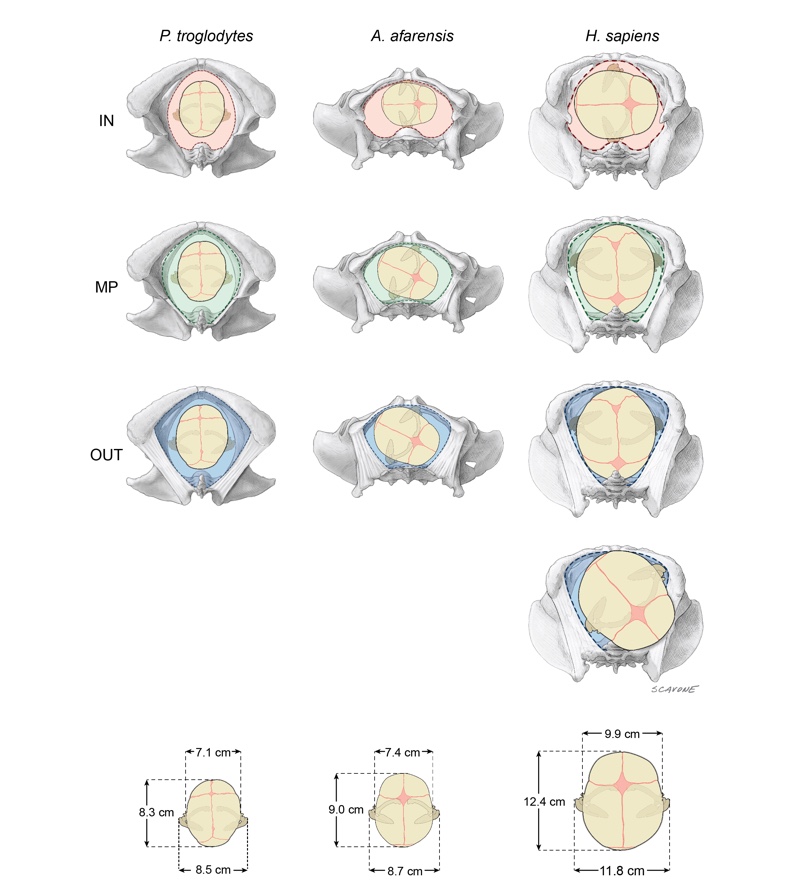

In primate babies, skulls are longer from the faces to the backs of the bodies than compared with from the forehead to the chin or from left to right. In most primates, the birth canal is similarly longer in that direction: lengthwise from the front to the back of a female's body. There is often plenty of room for most primate newborns as they exit the birth canal, so most primate mothers do not need help when they give birth. Instead, "mothers can just reach down and assist with their own births," said study lead author Jeremy DeSilva, a paleoanthropologist at Dartmouth College in Hanover, New Hampshire.

In contrast, in modern humans, the width of the birth canal, extending from the right to the left of the body, is bigger than the length. As such, babies enter the birth canal facing sideways. As the baby's head progresses out of the canal, it rotates to face the mother's back so the shoulders can then fit through. Human babies fit very snugly in birth canals, so human mothers generally require at least some assistance during birth, the study showed.

The absence of complete, undistorted fossil pelvises from female hominins — the group of species that consists of humans and their relatives dating after the split from the chimpanzee lineage — makes it difficult to see how hominin birth canals evolved over time and when rotations might have become common during childbirth, the researchers said. Some scientists have argued that rotation began only when brains became bigger with the human lineage, Homo. Others have suggested that rotation happened with the smaller-brained australopith lineage, Australopithecus.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Australopithecus afarensis is one of the earliest known relatives of humanity that has a skeleton built for walking upright. The species included the famed 3.2-million-year-old Lucy. Members of the Australopithecus lineage, known as australopiths or australopithecines, lived about 2.9 million to 3.8 million years ago in East Africa, and are among the leading candidates to be direct ancestors of the human lineage.

Prior analyses of how early hominins gave birth often focused on the baby's head and the mother's pelvis, with little attention paid to newborn's shoulders, DeSilva and his colleagues said. However, they noted that humans and apes have broad, rigid shoulders, and early hominins likely did as well. Personal experience helped prompt DeSilva to investigate the role that infants' shoulders played in early hominin birth, he said.

"With the birth of my own children, I started to get very interested in how Australopithecus gave birth and parented their children millions of years ago," DeSilva said.

To study these questions, DeSilva's team analyzed the fossil pelvis of Lucy and came up with a mathematical model describing how newborns might have made their way through Lucy's birth canal. "What we found with Lucy was very much in between that of chimpanzees and humans," DeSilva told Live Science.

There are no known fossils of any newborn australopiths. So, the researchers modeled the shape and size of an A. afarensis infant's head by assuming it had the same dimensions as a newborn chimpanzee's head but with a slightly larger size. They made this assumption because the average A. afarensis's adult skull capacity was about 20 percent bigger than that of modern chimpanzees, the researchers said.

In addition, the researchers said they estimated the width of an A. afarensis baby's shoulders by looking at the relationship between the shoulder widths of adult and newborn primates such as humans, chimps, gorillas, orangutans and gibbons, and by examining the width of an adult A. afarensis' shoulders.

"This is the first time the width of the shoulders has been considered in an attempt to reconstruct childbirth in early hominins," DeSilva said. "I'm excited anytime we can take these old fossils and bring them back to life and reconstruct what our ancestors and extinct relatives were doing."

Based on their models, the researchers suggested that, as happens in humans, a baby A. afarensis would have entered the birth canal sideways. However, the researchers also suggested that an infant A. afarensis would have had to tilt only a bit to make way for its shoulders as its head slid down the birth canal, instead of its head rotating 90 degrees as happens with human babies during childbirth.

"I think we have a tendency to think about Australopithecus and about Lucy as being quite ape-like. Sure, they walked on two legs, but in most other ways, we imagine them to be like modern apes," DeSilva said. "For some aspects of their life, this is probably true, but in terms of childbirth, our findings would suggest that they were more like us — not exactly like us, but more like us." [Image Gallery: Our Closest Human Ancestor]

The scientists did note that there was a tight fit between the infant A. afarensis and its birth canal. This suggests that australopiths may have had difficulty during labor just like modern humans, the scientists said.

"Because their mechanism of birth would benefit from having helpers, it paints a picture of Australopithecus as a much more social animal, perhaps helping one another out during childbirth," DeSilva said. "The origins of midwifery may very well extend back over 3 million years."

These findings suggest that the evolution of rotation during birth may have occurred in two stages, the researchers said. First, after hips designed for upright walking evolved, infants started rotating a bit in the birth canal so it could accommodate the head and shoulders. Then, as brains got bigger in the human lineage, full rotation began happening during childbirth, the study said.

DeSilva said that future research can examine what childbirth was like for other hominins, such as Australopithecus sediba, a potential ancestor of the human lineage.

The scientists detailed their findings online April 12 in the journal The Anatomical Record.

Original article on Live Science.