Life may have rebounded 'ridiculously fast' after the dinosaur-killing asteroid impact

After the asteroid smashed into Earth around 66 million years ago, it didn't take life that long to rebound, a new study finds.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

New species may have evolved surprisingly quickly after the asteroid impact that wiped out the nonavian dinosaurs, researchers have found.

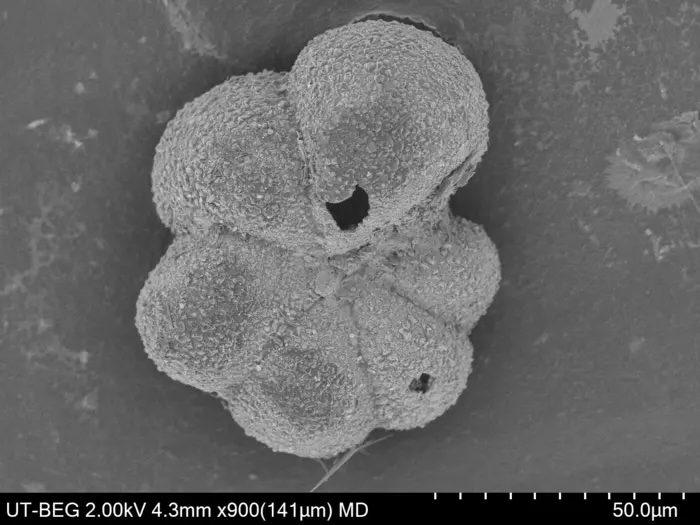

New plankton species may have appeared less than 2,000 years after the Chicxulub impact, which occurred about 66 million years ago, adding to an ongoing debate over how quickly new species arose in the wake of the collision. This suggests life rebounded much faster than scientists previously thought, researchers report in a study published Jan. 21 in the journal Geology.

"It's ridiculously fast," study co-author Chris Lowery, a paleoceanographer at the University of Texas Institute for Geophysics, said in a statement. "This research helps us understand just how quickly new species can evolve after extreme events and also how quickly the environment began to recover after the Chicxulub impact."

After the roughly 7.5-mile-wide (12 kilometers) asteroid struck off the coast of the Yucatán Peninsula in the Gulf of Mexico, dust and soot from the impact temporarily blocked out the sun. Cold, dark conditions lasted about 10 years, and roughly 75% of plant and animal species went extinct.

Based on estimates of how quickly sediment accumulated in the ocean and when fossils of new plankton species, such as Parvularugoglobigerina eugubina, started to appear, many experts think it took about 30,000 years for the first new species to show up.

But that estimate assumes that ocean sediments built up at a constant rate over that time period. Although that's often the case in ocean environments, it wasn't necessarily true after the Chicxulub impact.

In the new study, the researchers turned to a different marker: helium-3. This isotope falls to Earth with interplanetary dust at a constant rate. By measuring the helium-3 throughout a sediment layer, scientists can tell how long it took that layer to build up. For the study, the researchers used previously collected helium-3 measurements from six sites to calculate when new fossil species arrived.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Based on this analysis, P. eugubina appeared an average of 6,400 years after the impact across those six sites, the team found. At some sites, the new calibration suggests that other species likely emerged even sooner, less than 2,000 years after the asteroid struck. Between 10 and 20 species of plankton appeared within about 11,000 years, though there's still some debate over which fossils count as separate species, according to the study.

"The speed of the recovery demonstrates just how resilient life is," study co-author Timothy Bralower, a geoscientist at Penn State, said in the statement. "To have complex life reestablished within a geologic heartbeat is truly astounding."

New species typically take millions of years to develop, but that process can speed up during times of stress, such as after the asteroid impact.

That recovery may help give scientists a sense of how quickly new species could arise in response to human influence. "It's also possibly reassuring for the resiliency of modern species given the threat of anthropogenic habitat destruction," Bralower added.

Lowery, C. M., Bralower, T. J., Farley, K., & Leckie, R. M. (2026). New species evolved within a few thousand years of the Chicxulub Impact. Geology. https://doi.org/10.1130/g53313.1

Evolution quiz: Can you naturally select the correct answers?

Skyler Ware is a freelance science journalist covering chemistry, biology, paleontology and Earth science. She was a 2023 AAAS Mass Media Science and Engineering Fellow at Science News. Her work has also appeared in Science News Explores, ZME Science and Chembites, among others. Skyler has a Ph.D. in chemistry from Caltech.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus