New Wisdom on Wisdom Teeth

Anyone who has had their wisdom teeth removed knows that they’re a real pain in the … mouth.

Now, a study detailed in the Sept. 27 issue of the journal Nature finds these annoying teeth may only exist because of a weakness in a developmental mechanism that allows them to cram their way into the back of the jaw.

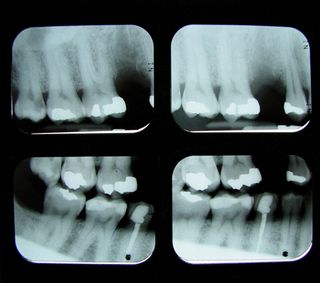

Molars are the rearmost teeth in the mouth of most mammals. Adult humans have 12 molars (three on each side of the upper and lower jaws), and the last of each group is called the wisdom tooth.

Molars usually pop up from front to back, with the wisdom teeth appearing last between the ages of 16 and 24. If they start to crowd the jaw line and push the other teeth around, then its time for that dreaded dental procedure: the wisdom-tooth extraction.

One thing about molars that has perplexed scientists is why some people have very large wisdom teeth, while others (lucky for them) might not have any at all.

To help answer this question, researchers at the University of Helsinki in Finland cultured mice teeth in a Petri dish.

They found that the balance between two molecular mechanisms, activation and inhibition, govern how many teeth form from the tooth germ (the small bud of tissue that will later form the tooth) and how big the teeth are.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

When the two mechanisms are in balance, all three teeth form and are about the same size.

But if the two don't balance, the size of the teeth differs. If activation wins out, each tooth is successively larger, with the wisdom tooth becoming the bully of the bunch and causing a real mouth-ache. In extreme cases, a fourth molar might even rear its ugly head.

On the other hand, if inhibition wins out, the teeth get successively smaller, so the wisdom tooth is the runt of the litter. Run to its extreme, this situation could prevent the wisdom tooth from forming altogether.

Most early humans had all their wisdom teeth, with all of them measuring about the same size, so the two forces were likely in balance then, said study team member Jukka Jernvall.

But now, our wisdom teeth are usually smaller than the rest of the molars, meaning inhibition might be winning out evolutionarily, Jernvall told LiveScience, though this differs from person to person.

Even with wisdom teeth becoming smaller, they can still cause problems because the human jaw has also become smaller with time, which could be because as we learned to cook, our food became softer and required less power to chew, Jernvall said.

So dentists should be in good business for a long time to come.

- 10 Things You Didn't Know About You

- Top 10 Useless Limbs (and Other Vestigial Organs)

- Body Quiz: The Parts List

Andrea Thompson is an associate editor at Scientific American, where she covers sustainability, energy and the environment. Prior to that, she was a senior writer covering climate science at Climate Central and a reporter and editor at Live Science, where she primarily covered Earth science and the environment. She holds a graduate degree in science health and environmental reporting from New York University, as well as a bachelor of science and and masters of science in atmospheric chemistry from the Georgia Institute of Technology.

Most Popular