Photos of the World's Smallest (and Cutest) Owl

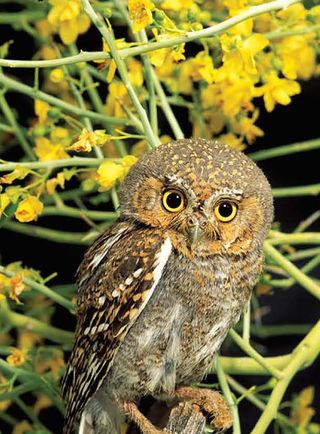

Elf owls

Ecological and geological diversity just might be the biggest surprise for anyone who visits one of the five great North American deserts for the first time. Far from rolling miles of barren sand dunes, the deserts of North America are alive with unique species of plants and animals that not only survive but thrive in the harsh temperatures and low precipitation found across the continent's arid regions. In his 1968 book, "Desert Solitaire," author/activist Edward Abbey said of the desert in which he lived, "This is the most beautiful place on Earth."

Cutie-patootie

And as so commonly occurs, found within this "most beautiful place on Earth" is a unique and quite frankly adorable creature that has adapted not only its way of life but even its size to successfully carry on within the desert environments. The diminutive Whitney's elf owl, Micrathene whitneyi, is a common resident of the riparian areas of the Sonoran and Chihuahuan deserts. It is the smallest owl found in the world and shares the title as the world's lightest owl weighing a mere 1.4 ounces (40 g). A fully grown male elf owl will reach 4.9 to 5.7 inches (12.5 to 14.5 cm) in length and have a wingspan of 10.5 inches (27 cm). The juvenile elf owl, shown here, is being assisted by a National Park Ranger after the small elf owl fell from its nesting hole while attempting its initial flight.

Mobile homes

The home range of Whitney elf owls, shown above, changes over a yearly cycle. In the spring and summer, they are found in the arid deserts of the American Southwest and northern Mexico, where they breed and raise their young. They populate areas where cactus forests, woody canyons, plateaus or densely vegetated riparian areas are found. In winter, they migrate south, spending the cooler months of the Northern Hemisphere in the warm, coastal regions of central Mexico. Four subspecies of elf owls are recognized: Micrathene whitneyi idonea is found only in the southern tip of Texas and northern Mexico; Micrathene whitneyi sanfordi is a resident of the southern tip of Baja Sur, California; and Micrathene whitneyi graysoni lives on the island of Socorro off the tip of Baja Sur.

Distinctive coloring

Irregular orangey-brown spotting covers a rusty-brown feathered backside and wings, giving the owl an ideal camouflage for a life spent living in a desert landscape dominated with shades of brown. Light, whitish spotting becomes more common on the crown of the head. A line of white feathers highlights the edge of each wing. The chest and belly are a mixture of white, brown and orange streaking feathers. Some of the primary and secondary flight feathers are also tipped in white.

Always surprised

The eyebrows of the Whitney elf owls are prominent in their distinct white feathers. The owl's facial mask is dominated by shades of orange. The bill is gray with a horn-colored tip. The iris of each large eye is dominated by yellow. Unlike most owls, the Whitney elf owl does not have "ear tufts" or any protruding feathers on its small rounded head. Like other owls, elf owls have a series of uniquely designed softened feathers along the edge of their wings that allows for silent flight.

Unique nesting choices

One of the more unique behaviors of these tiny owls has to do with nest-building. Being so small, predators would be a great danger for a nest-sitting female and her young hatchlings. The Whitney elf owl solved this dilemma by learning to nest in abandoned woodpecker holes. In the Sonoran Desert, the Gila woodpecker, Melanerpes uropygialis, and the gilded flicker, Colaptes chrysoides, are responsible for carving out nesting cavities in the soft pulp of giant cacti. As seen in the photo, the openings leading into the nesting cavities are all that can be seen when looking at this giant sentinel of the desert — which is displaying both its white flowers and red fruits. In regions where saguaro cacti do not grow, elf owls will nest in the abandoned woodpecker holes made in local trees and even telephone poles.

Useful work

The nesting cavity created by the two desert woodpeckers is known as a saguaro boot. These boots, as shown here, are formed inside the saguaro's fleshy skin as a result of the cactus secreting a resinous fluid in response to the "wound" caused by the excavating woodpeckers. When exposed to air, this resin hardens into a solid, callus tissue that prevents further moisture loss from the saguaro, creating a secure nesting hole for first the woodpeckers and then others species of small desert-dwelling birds like elf owls.

Desert honeybees will often make hives within the saguaro boot, creating a cavity of sweet honey. When the saguaro cactus dies, the fleshy skin will deteriorate, but the hard saguaro boot remains, resistant to decomposition. Native people of the Sonoran Desert once used these "boots" as containers, sometimes even as natural canteens for carrying water. Into these secure nesting "boots" a female elf owl will lay two to four white eggs.

Turning on the charm

The breeding season for elf owls in the southwest Sonoran Desert occurs in May and June. Males will sing loudly through the night to both impress a female and defend his territory. The male most often will sing from inside his already claimed saguaro nesting holes, trying to lure a female to join him inside the cavity. During their courtship, the male will actively feed his prospective partner. Once mating occurs and the eggs are laid on the rough callus floor of the saguaro boot, the female alone will incubate the eggs. The eggs begin hatching some 21-24 days after being laid. For the first two weeks, the female does not leave her hatchings, as the male brings food into the nesting hole for both mom and her young.

After the young are 2 weeks old, both parents will leave the nest to hunt and provide food for the young. The young owls begin to leave the nest some 28 days after hatching but remain under the watchful eyes of their parents for an additional week to 10 days.

On the hunt

Insects, spiders, scorpions and other arthropods are the primary diet of the Whitney elf owl. Mom or Dad will remove the poisonous stinger of a captured scorpion before feeding the scorpion to their young. Large nocturnal desert beetles are a common food source. They hunt primarily in the low light of dusk and dawn. They have excellent hearing and often locate and catch their prey by sound rather than by their sight.

Following the food

Elf owls are one of the two species of owls found in North America that actually migrate — the second being the small, Western pine forest dwelling Flammulated owl, Psiloscops flammeolus, seen here. Both of these small, nocturnal owl species depend on flying insects as their primary source of food, so when winter arrives in their breeding grounds, they follow the insects to the warmer climes of Mexico. The Whitney elf owl commonly leaves its summer Sonoran Desert home by late September and spends the winter months in the insect-filled forests of central and southern Mexico.

Tricky critters

Being so small, elf owls are in constant danger from the many predators common to the Sonoran Desert, such as snakes, coyotes, bobcats and ringtail cats, Bassariscus astutus. Larger owls, hawks and jays will also attack and capture these small owls. Few, if any, predators can capture the tiny owls when they are securely inside their home saguaro boot; but when they leave that boot, danger abounds. Elf owls are by nature nonaggressive, preferring to flee rather than fight. But groups of elf owls have been known to cooperatively mob intruders and predators. Elf owls have been documented "playing possum" when they are outside their secure home cavity and danger appears, remaining motionless as if dead until the danger passes.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.