Space Station to Host Coldest Spot in the Universe

The International Space Station (ISS) will soon host the coldest spot in the entire universe, if everything goes according to plan.

This August, NASA plans to launch to the ISS an experiment that will freeze atoms to only 1 billionth of a degree above absolute zero — more than 100 million times colder than the far reaches of deep space, agency officials said.

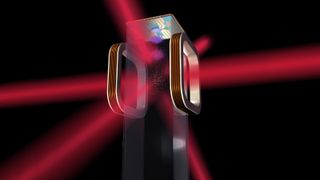

The instrument suite, which is about the size of an ice chest, is called the Cold Atom Laboratory (CAL). It consists of lasers, a vacuum chamber and an electromagnetic "knife" that together will slow down gas particles until they are almost motionless. (Remember that temperature is just a measurement of how fast atoms and molecules are moving.) [Watch a video about the CAL]

If successful, CAL could help unlock some of the universe's deepest mysteries, project leaders said.

"Studying these hypercold atoms could reshape our understanding of matter and the fundamental nature of gravity," Robert Thompson, a CAL project scientist at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) in Pasadena, California, said in a statement. "The experiments we'll do with the Cold Atom Lab will give us insight into gravity and dark energy — some of the most pervasive forces in the universe."

Attempts to create Bose-Einstein condensates on Earth have been only partially successful to date. Because everything on Earth is subject to the pull of gravity, atoms and molecules tend to move toward the ground. This means the effects can only be seen for fractions of a second. In space, where the ISS is in perpetual freefall, CAL could preserve these structures for 5 to 10 seconds, NASA officials said. (Future versions of CAL may be able to hold on for hundreds of seconds, if technology improves as expected, officials added.)

The researchers hope CAL observations will lead to the improvement of several technologies, such as quantum computers, atomic clocks for spacecraft navigation and sensors of various types — including some that could help detect dark energy. The current model of the universe suggests we can only see about 5 percent of what's out there. The remainder is split between dark matter (27 percent) and dark energy (68 percent).

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"This means that even with all of our current technologies, we are still blind to 95 percent of the universe," JPL's Kamal Oudrhiri, CAL deputy project manager, said in the same statement. "Like a new lens in Galileo's first telescope, the ultra-sensitive cold atoms in the Cold Atom Lab have the potential to unlock many mysteries beyond the frontiers of known physics."

CAL, which was developed at JPL, is scheduled to fly to the ISS this August aboard SpaceX's robotic Dragon cargo capsule. Final testing is underway ahead of CAL's shipment to the launch pad in Cape Canaveral, Florida, NASA officials said.

Follow Elizabeth Howell @howellspace, or Space.com @Spacedotcom. We're also on Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.