How an Orangutan Became a Master of Tying Knots

Chris Herzfeld is a philosopher of sciences at the Ecole des Hautes Etudes en Sciences Sociales (School for Advanced Studies in the Social Sciences) in Paris, where she specializes in the history of primatology and the history of the human-ape relationship. As a philosopher at the Ecole Normale Supérieure in Paris, Dominique Lestel works on animality, human-animal relations and posthuman studies. They contributed this article to Live Science's Expert Voices: Op-Ed & Insights.

Great apes living in the wild have developed diverse and impressive technical know-how: They construct nests, make and use tools, hunt smallprey with spears, and shape leaf sponges and various instruments of comfort. For example, they use cushions made with leaves, sticks for scratching and leaves as umbrellas.

But they do not tie knots.

Knot tying is usually viewed as an ability unique to humans. However, researchers such as Roger Fouts at Central Washington University, Terry L. Maple at Zoo Atlanta, Michael Beran at Language Research Center at Georgia State University, Lyn Miles at the University of Tennessee and many others have reported that certain "talking apes" (those that can communicate with a human language, such as American Sign Language or another iconic language), rehabilitated apes or zoo-housed apes can untie knots and sometimes even make knots.

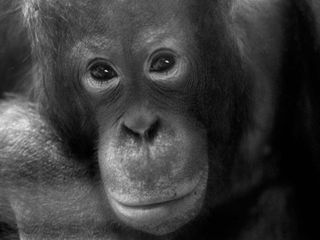

Among these knot-tying apes, one female orangutan has proven to be a true tying expert. When we met Wattana, she was part of a small community of apes who lived in the middle of Paris in one of the most ancient zoos in the world — founded at the end of the 18th century — the Ménagerie du Jardin des Plantes (Botanical Garden Zoo) at the National Museum of Natural History in Paris. Wattana was born on Nov. 17, 1995, at Antwerp Zoo in Belgium. Transferred soon after to Stuttgart Zoo in Germany to be reared by the zookeepers there, she then traveled to Paris in May 1998. [Great Apes: All 4 Gorillas Subspecies ]

A master knotsmith

Wattana is a true knot-tying virtuoso. We provided her with rolls of paper, strings, laced shoes, pieces of garden hose — and she made knots using all of those materials. She was not rewarded or even encouraged to do so, and, even sometimes, preferred to continue her knot tying rather than eating her meal.

She also uses the iron rings, the wire mesh or the wooden pole of her enclosure as supports for making knots or "weaving" several strings to one another. She is a "quadrumana," tying knots using her hands and feet, and sometimes even her mouth. With this rare orangutan ability, Wattana has developed her own style of knots on a kind of "orangutan modality."

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Learning to tie knots

However, her technical abilities do not explain why Wattana ties knots and how she learned this skill.

After reviewing the relevant literature and correspondence with recognized great-ape specialists, we found about 20 knot-tying apes. About three-quarters of them are females. Six are "talking apes."

All of these knot-tying apes were human-reared. This is not surprising. Human context allows great apes to access substantial new learning opportunities. Captive orangutans have more free time, access to materials that provide them occasions to show off unexpected abilities and favorable circumstances (for instance, safe access to the land where it is easier to handle different materials than in the trees).

When the apes enter the human world, they have to adopt our places, our objects, our diets, and our habits. They "meet" the knots in their enclosure, on our boots and in different aspects of our life. They are surrounded by substantially more human beings than apes. Humans become their partners and assume the role of charismatic leaders. The apes observe them intently and are deeply interested in their know-how. [Chimps vs. Humans: How Are We Different?]

Different primatologists have shown that there are two basic and intertwined learning modes for great apes: "social learning" and "observation learning." They learn by observing, peering at and imitating people with whom they maintain deep ties, and acquire human abilities that fascinate them. When Wattana was still an infant, her keepers entered her enclosure to take care of the three young orangutans living at the Ménagerie at that time. She observed her caretakers carefully when they had to redo their shoelaces, after the small orangutans untied them. Several primatologists and keepers have reported that orangutans are fascinated by bootlaces. Thus the young female got up very close to the shoes and peered at the tying of the strings. Then, she tried to recreate it herself. She practiced knot tying as often as possible, and learned to make knots.

Knots and nest building

How could scientists explain some apes' connection with knot tying? All great apes make nests every day in the wild. Knot tying is probably closely related to nest building, which is a kind of fibro-constructive technique, meaning it involves using fibers, strings or soft materials to make different objects, instruments of comfort and shelters. "Weave" is a term often used in descriptions of nest building. Anthropologist Tim Ingold of the University of Aberdeen in Scotland proposed that scientists should regard "making" as a modality of "weaving." In fact, thinking about "weaving" rather than "making" (as the production of an object) allows us to think about the process, the movements and the rhythm of the practitioner, more than about an action or a product disconnected from the manufacturing process, Ingold explained in 2010 in the Cambridge Journal of Economics.

Ingold advanced the idea that the nest-building skills could have led to the physical and cognitive abilities to make and use tools. In this context, the ability to tie knots — at first sight, so derisory — could be an indication of important dispositions that allow the emergence of different sophisticated technological skills among some of our closest relatives. Furthermore, when we examine the list of knot-tying apes, we see that over half of them are orangutans, which appear particularly proficient in knot tying. [Sleeping Soundly: See Photos of Primate Nests]

Again, their technological ingenuity is probably connected to their forest expertise, especially their capability to construct woven nests, to make some objects to protect themselves (e.g., leaf gloves or vegetal hats) or some elements of comfort (e.g., leaf cushions), and tools to get their food. Food is often difficult to obtain or eat in the Indonesian forests. For instance, the orangutans have to handle spiny plants, fruits with shells, and nuts with hard shells. To adapt to forest living, animals must develop numerous sophisticated skills, which, in turn, yields some byproducts. For example, talents for complex tasks, such as weaving and tying, can be expressed in environments that are totally different from their native forests: families (into which "talking apes" were integrated), sanctuaries or zoos.

Why tie knots?

Several scientists have observed captive orangutans twisting, knotting and tying wood-wool and different materials. Numerous primatologists have reported that orangutans show an impressive mechanical genius. This is also undoubtedly connected to their capacity for insight, their great willingness to manipulate objects and their tendency toward solitary games involving objects.

Wattana's knots also lead us to examine the importance of the weaving and fibro-constructive technique in the daily great apes' life, and to better understand how great apes can "build a world" in places completely different from their original environment.

In addition, knot tying is a perfect example of a technical skill, consisting of a series of rhythmically incorporated movements, that is impossible to conceptualize and to perform by mentally following a series of predetermined gestures. It is a generative process, involving motions memorized by the body and connected with the rhythm, such as that used by a pianist when playing the piano.

The pleasure Wattana gets in tying knots encourages her to practice the skill. Thus, pleasure was a key motivation for Wattana to become a knot-tying expert. When an individual enjoys practicing a specific activity, he is stimulated to further practice it, becoming more and more efficient and, in turn, developing a true expertise. This expertise increases the pleasure to practice, pushing the practitioner to exercise. It is clear that enjoyment probably plays a key role in encouraging the development of abilities, skills and even expertise.

Today, Wattana is living in Apenheul Primate Park in the Netherlands. The last time we visited her, several years after the time we spent together at the Ménagerie du Jardin des Plantes, we gave her a red ribbon. Then, we went away. When we came back, she had used the ribbon to make a knot on the mesh of her enclosure.

Follow all of the Expert Voices issues and debates — and become part of the discussion — on Facebook, Twitter and Google+. The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher. This version of the article was originally published on Live Science .

Most Popular