Weak Underbelly Makes US Capital Vulnerable to Earthquakes

The nation's capital sits on shaky ground that jiggles like pudding when earthquakes rattle the East Coast.

Researchers are analyzing seismic shaking underneath Washington, D.C., to better predict future earthquake damage to federal buildings and monuments. The study was sparked by the 2011 Virginia earthquake, a magnitude-5.8 temblor that cracked the Washington Monument and the National Cathedral.

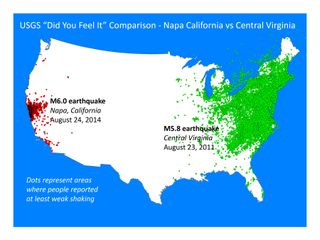

The 2011 quake struck near the town of Mineral, Virginia, about 40 miles (64 kilometers) northwest of Richmond. It was felt from New England to Chicago. Afterward, nearly 140,000 people filled out an online U.S. Geological Survey questionnaire that rates the strength of shaking. The responses showed the most intense shaking was felt around the Chesapeake Bay, in the District of Columbia and southern Maryland. [Image Gallery: This Millennium's Destructive Earthquakes]

"The reports showed higher levels of ground shaking than you would have expected for an earthquake that far away," said study leader Thomas Pratt, a USGS research geophysicist.

To understand why strong earthquake tremors hit the capital, the USGS partnered with Virginia Tech in 2014 to install 27 seismometers around the District of Columbia. The sensitive instruments pick up seismic waves in the area from quakes and urban noise.

The study's early results suggest a thin layer of weak ocean sediments is to blame for D.C.'s earthquake problems. The layer is about 655 feet (200 meters) thick, and it was deposited when sea level was higher than it is now, Pratt said.

The findings were presented on April 21 at the annual meeting of the Seismological Society of America in Pasadena, California.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The ocean muds and silts cap old, hard crystalline bedrock that is similar to granite. The two layers respond so differently to shaking that seismic waves "see" a boundary between the ocean muck and the bedrock. Earthquake waves bounce off this boundary, zinging up and down underneath D.C. Result? The whole city wobbles like gelatin.

"The energy just echoes back and forth, so it makes for a much longer level of shaking," Pratt said. The shaking also feels stronger because of the contrast between the bedrock and the ocean deposits. It takes a lot of energy to shake hard rock, and when that energy gets into the weak muds, the ground shaking intensifies, Pratt said. "We are finding a significant amount of increased ground shaking because of these shallow deposits," he told Live Science.

The information collected during the study will help engineers retrofit historic buildings in the District of Columbia to better withstand earthquakes. East Coast earthquakes are rare events, but they are high-risk because buildings are not designed to withstand strong shaking.

"There aren't a huge number of earthquakes in the eastern U.S., but the effects could be devastating," Pratt said.

Follow Becky Oskin @beckyoskin. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Originally published on Live Science.