Wrinkly 'sac' with no anus probably isn't humans' earliest ancestor. (Thank goodness!)

The Saccorhytus is more closely related to penis worms and mud dragons.

An ancient creature that looks like an "angry Minion" with no anus is more closely related to penis worms and mud dragons than to humans, a new study suggests.

The 500 million-year-old Saccorhytus coronarius was previously tied to a group of animals called deuterostomes that produced vertebrates and humans, suggesting it was our earliest known ancestor. But a new research team has decided it's an ecdysozoan, a group that includes insects and marine invertebrates such as penis worms (priapulids) and mud dragons (Kinorhyncha), and which diverged from a common ancestor to humans much further back in evolutionary history.

The latest findings make an important amendment to the evolutionary tree and our understanding of how life developed, the researchers said.

Study co-author Philip Donoghue, a professor of paleobiology at the University of Bristol in the United Kingdom, told Live Science that the team was always confident that S. coronarius needed reclassification, but joked at the idea it was a relief for some of his colleagues. "I'm sure some people were relieved that we're not descended from wrinkly ball sacs," he said.

Related: Mammal ancestor looked like a chubby lizard with a tiny head and had a hippo-like lifestyle

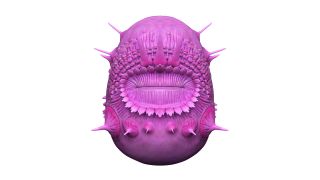

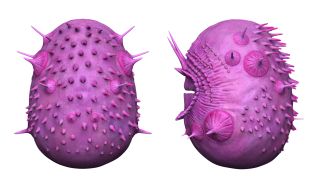

The early Cambrian species is only about 0.02 inches (0.5 millimeters) long and found in microfossils in the Shaanxi Province of Northwest China. The team used a type of particle accelerator called a synchrotron to produce detailed X-ray images of the fossil that revealed microscopic details about its body plan.

The original interpretation of S. coronarius, first published in 2017, concluded that the holes around its mouth were pores and potentially a precursor for gills, Live Science previously reported. The new research concluded that S. coronarius actually had spines that came through these holes, which broke off during fossilization.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The team constructed a digital 3D model of S. coronarius and compared it with different animal groups, before placing it among early ecdysozoans. It's a big move for the little creature and may lead to some scientific debate.

Karma Nanglu, a paleobiologist at Harvard University's Museum of Comparative Zoology, who was not involved in the new or the 2017 studies, told Live Science that there's still room for interpretation with S. coronarius. "I don't know if I'd go as far to say that this is a full-on correction [of the 2017 research]," he said. "It's an alternative interpretation and I think both of them are interesting and worthy of debate."

Nanglu described Saccorhytus as having the trifecta of components that make it very hard to interpret. "It's old, it's weird and it's small," he said. Because of these factors, major understanding can shift with the smallest of details.

"We're dealing with a time period where most major animal groups make their first appearance in the fossil record, either around that time or shortly after," Nanglu said. "And so even small interpretations of 'is this a spine that's been broken off or is this a true bonafide actual opening into the animal' carry huge ramifications for how we interpret the origins of these major groups."

The lack of anus is an important feature no matter what group Saccorhytus is in, as it contributes to the understanding of how body plans evolved. The new research suggests that early ecdysozoans had a greater range of body plan designs than previously thought and there may be more body plans waiting to be discovered.

S. coronarius could have spent its days catching prey in sediment on the sea floor, but Donoghue noted that scientists still have much more to learn about these ancient creatures.

"All we really know is that they're tiny, they have a mouth and no anus," Donoghue said. "Whatever went in their mouth had to come out of their mouth after they finished processing it. It's a strange way to live, but it worked for them I guess."

The study was published online Wednesday (Aug. 17) in the journal Nature.

Originally published on Live Science.

Patrick Pester is a freelance writer and previously a staff writer at Live Science. His background is in wildlife conservation and he has worked with endangered species around the world. Patrick holds a master's degree in international journalism from Cardiff University in the U.K.

Most Popular