Autistic Children Have More Trouble Searching for Items

Children with autism may have a harder time than other kids searching for items, such as a particular food in the grocery store, or keys inside a house, a new study suggests.

The results were surprising, the researchers said, because previous work had shown that autistic individuals are often superior to others at searching for visual cues in a small-scale environment, such as a table top or a computer screen.

But the new study suggested that when the scale is larger, autistic individuals have impairments. The findings may explain part of the reason why some autistic individuals have trouble living independently, the researchers said.

"[The results] might be important for our understanding of the problems autistic individuals have in their everyday life," said study researcher Iain Gilchrist, of the University of Bristol in England. "The problems they have aren’t just restricted to living or operating in the social world. These results suggest that they may have problems with quite a fundamental process that we all engage in all the time, which is foraging to find things," he said.

Searching for lights

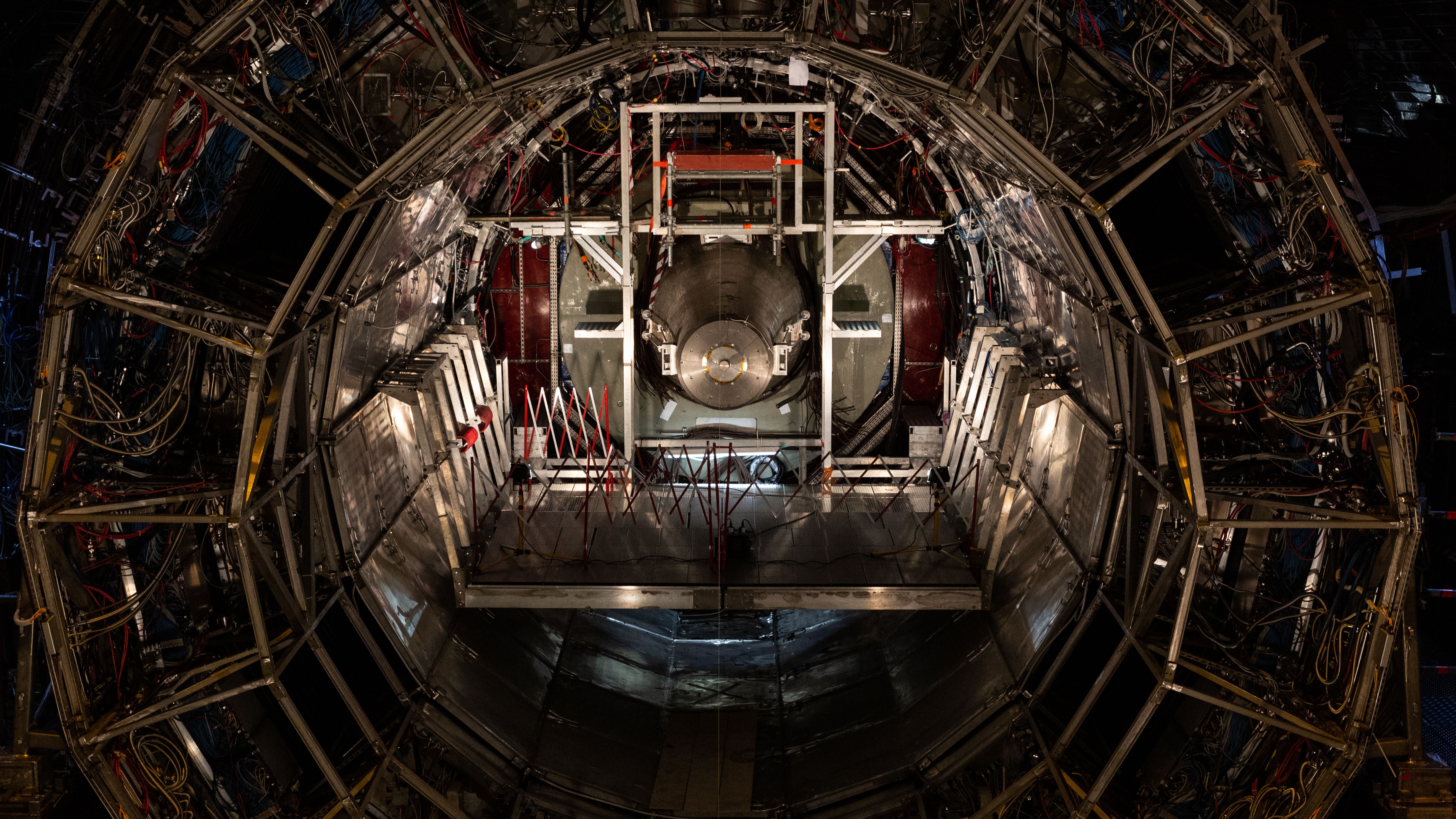

To simulate a real-world searching situation, Gilchrist and his colleagues used a special testing room containing about 50 red lights on the floor, arranged in a circle. All of the lights contained a central button, and some turned from red to green when the button was pushed. Children were told to find the "target" lights, or the ones that turned green.

Unbeknownst to the children, there were more target lights on one side of the room than the other.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

People with autism are known to be exceptional at figuring out the rules within a system — for example, a train timetable or prime numbers — a process known as systemizing. The researchers wanted to see whether the autistic children picked up more quickly on the fact that there were more target lights on one side of the room, and whether their searches would become systematic once they'd figured out the rule.

The study involved 20 children with autism, ages 8 to 14, and 20 children without autism, whose average age was 11.

Contrary to what was expected, the autistic children took longer than the other children to figure out that most of the target lights were on one side of the room.

"That knowledge about where things are more likely to be in your environment is really powerful, because it really helps you find things quickly," Gilchrist said. "You're not going to probably put your mobile phone into a kitchen cupboard or in the oven; you've more likely left it on the worktop."

Furthermore, the children with autism searched less systematically, or more randomly, than the other children.

And the autistic children were also more likely than the other kids to revisit lights they had already tested.

Seeing the trees, but not the forest

The researchers don't know why autistic children appeared to have a harder time with searching than other kids. But individuals with autism are known for focusing on details, and missing the forest for the trees, so to speak, Gilchrist said.

Such a local focus may prevent people with autism from seeing the broader view of their surroundings needed to search effectively and systematically, Gilchrist said.

It's also possible that that this tendency to get tied up in the details hinders their ability to orient themselves in space, Gilchrist said.

The results are published this week in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Pass it on: Children with autism may have an impaired ability to search for items in a real-world environment, such as searching for keys inside the home.

- Autism: Symptoms, Diagnosis and Treatments

- Some Brains Might Be Compensating for Autism Risk

- Magic Trick Based on Social Cues Fools People with Autism

Follow MyHealthNewsDaily staff writer Rachael Rettner on Twitter @Rachael_MHND.

Rachael is a Live Science contributor, and was a former channel editor and senior writer for Live Science between 2010 and 2022. She has a master's degree in journalism from New York University's Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program. She also holds a B.S. in molecular biology and an M.S. in biology from the University of California, San Diego. Her work has appeared in Scienceline, The Washington Post and Scientific American.