50 interesting facts about Earth

From extreme climates to peculiar creatures, here are some top facts about Earth.

- 1. Position

- 2. Squashed shape

- 3. Earth's waistline

- 4. On the move

- 5. Planet's orbit

- 6. Earth's age

- 7. Recycled planet

- 8. Moonquakes

- 9. Largest earthquake

- 10. Hottest spot

- 11. Coldest place

- 12. An extreme continent

- 13. Largest stalagmite

- 14. Uneven gravity

- 15. Creeping magnetic pole

- 16. Flipping pole

- 17. Tallest mountain tie

- 18. Two moons?

- 19. Temporary moons

- 20. Walking rocks

- 21. Impressive expeditions

- 22. Longest mountain chain

- 23. Largest living structure

- 24. Deepest spot

- 25. Lowest point on land

- 26. Lakes can explode

- 27. Losing fresh water

- 28. Melting glaciers

- 29. Purple Earth

- 30. Earth is electric

- 31. Earth's seas

- 32. Gold abundance

- 33. Raining cosmic dust

- 34. The sun's light

- 35. The moon's collision

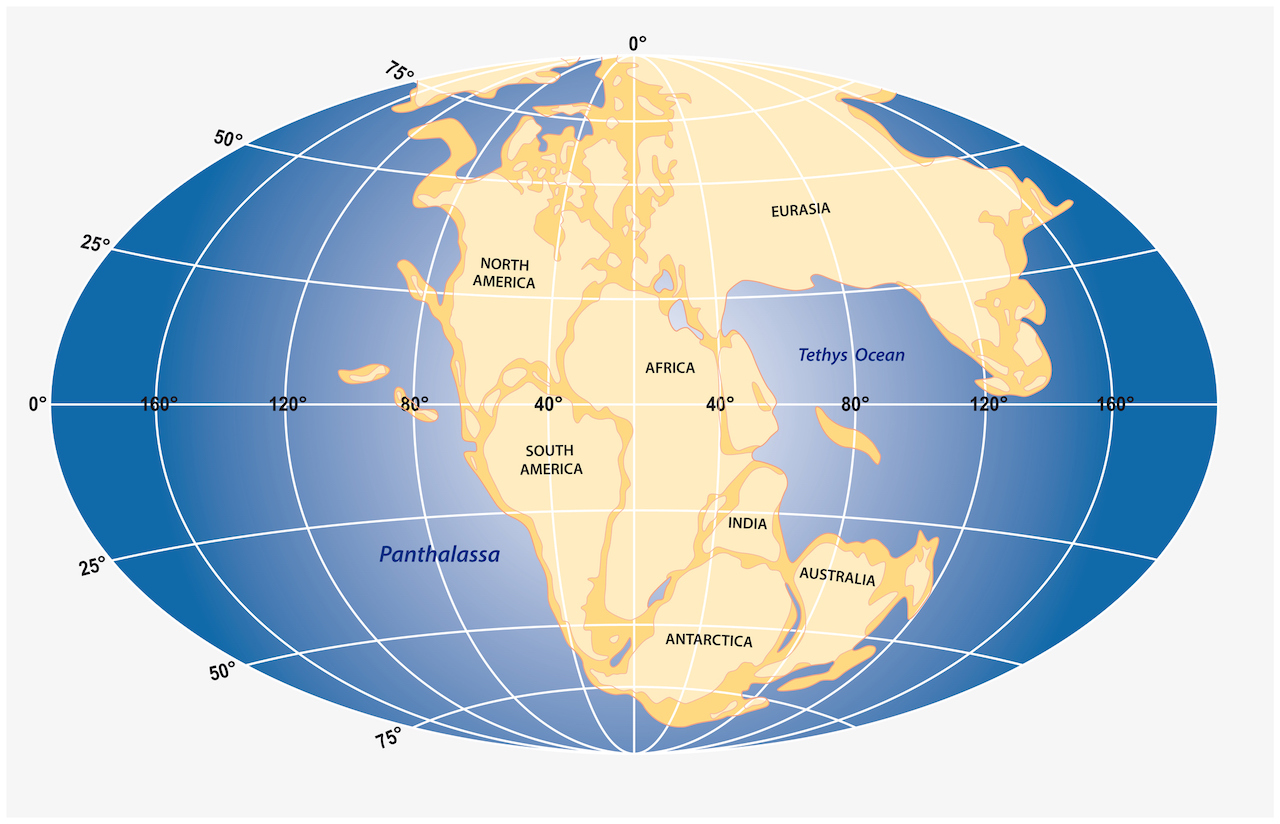

- 36. History's supercontinent

- 37. Mountain creation

- 38. Most active volcanoes

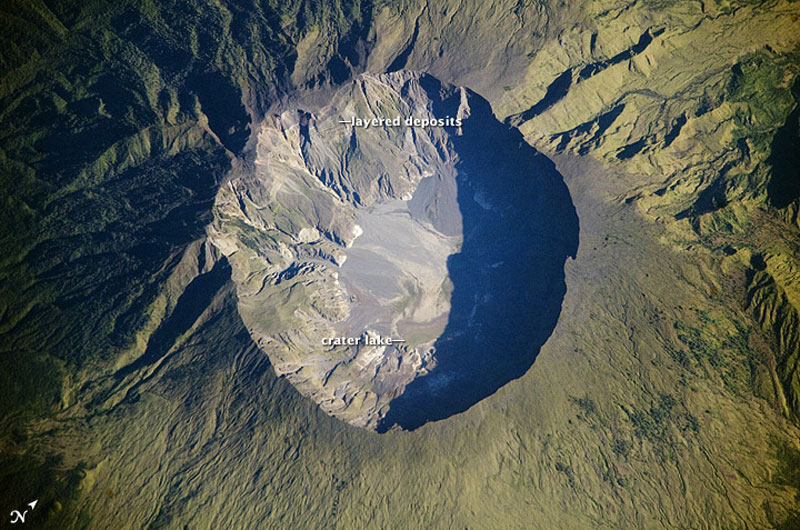

- 39. Colossal eruption

- 40. Crowded coastlines

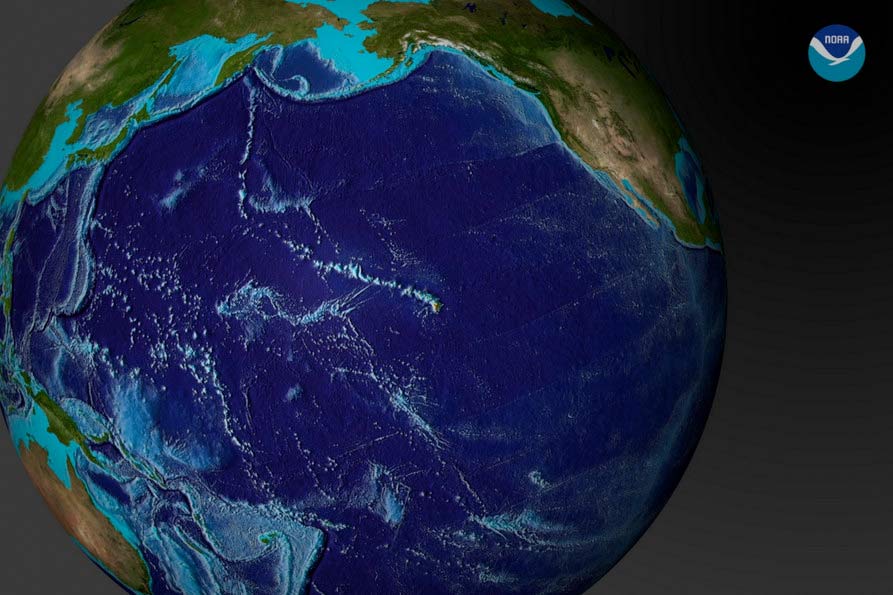

- 41. Biggest basin

- 42. Giant trees

- 43. Largest living thing

- 44. Smallest mammal

- 45. Most populated city

- 46. Most open space

- 47. Driest spot

- 48. First to the South Pole

- 49. Other Earth-like planets

- 50. Dancing lights

- Additional resources

- Bibliography

Did you know that our planet is rocketing around the sun at 67,000 mph? Or that it may once have been purple? Here are 50 facts about Earth.

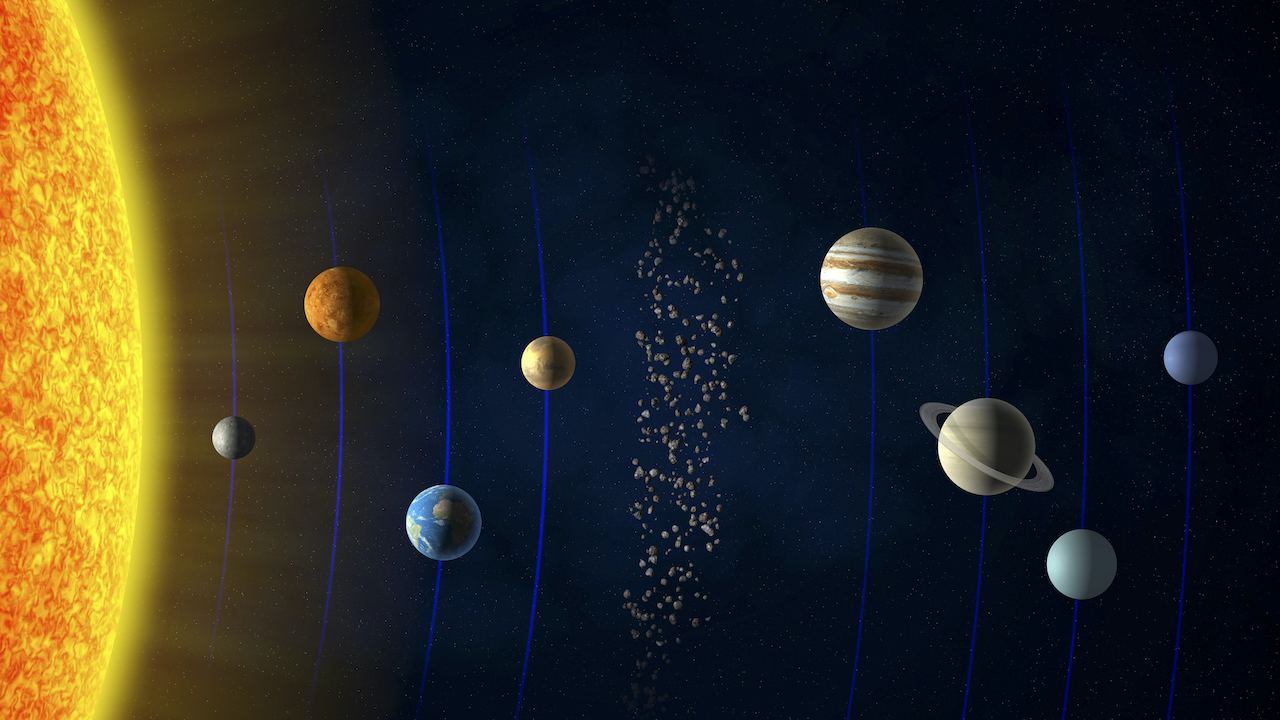

1. We're the third rock from the sun

Our home, Earth, is the third planet from the sun, the fifth largest planet in our solar system, with a radius of 3,959 miles, and the only world known to support an atmosphere with free oxygen, oceans of liquid water on the surface and life. Earth is one of the four terrestrial planets, according to NASA: Like Mercury, Venus and Mars, it is rocky at the surface.

2. Earth is squashed

Earth is not a perfect sphere, but rather a geoid, which means it bulges at the equator. According to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), as Earth spins, gravity points toward the center of our planet (assuming for explanation's sake that Earth is a perfect sphere), and a centrifugal force pushes outward. But since this gravity-opposing force acts perpendicular to the axis of Earth, and Earth's axis is tilted, centrifugal force at the equator is not exactly opposed to gravity.

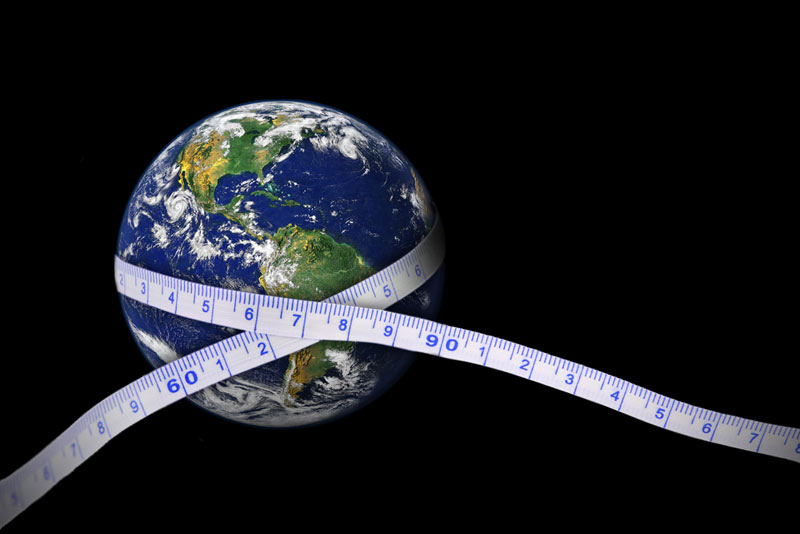

3. The planet has a waistline

Gravity pushes extra masses of water and earth into a bulge, or "spare tire" around our planet. At the equator, the circumference of the globe is 24,901 miles (40,075 kilometers), according to Space.com. Bonus fact: At the equator, you would weigh less than if standing at one of the poles.

4. Earth is on the move

You may feel like you're standing still, but you're constantly moving — fast. Depending on where you are on the globe, you could be spinning with the planet at just over 1,000 miles per hour, according to Space.com.

People on the equator move the fastest, while someone standing on the North or South pole would be perfectly still. (Imagine a basketball spinning on your finger. A random point on the ball's equator has farther to go in a single spin as a point near your finger. Thus, the point on the equator is moving faster.)

5. The planet moves around the sun

The Earth isn't just spinning: Earth orbits the sun every 365.25 days, traveling at an average speed of 18.5 miles per second. Thats 67,000 miles (107,826 km) per hour, according to the American Physical Society.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

6. Earth is billions of years old

Researchers calculate the age of the Earth by dating both the oldest rocks on the planet and meteorites that have been discovered on Earth (meteorites and Earth formed at the same time, when the solar system was forming). Their findings? Scientists estimate that Earth is around 4.54 billion years old, according to the National Center for Science Education.

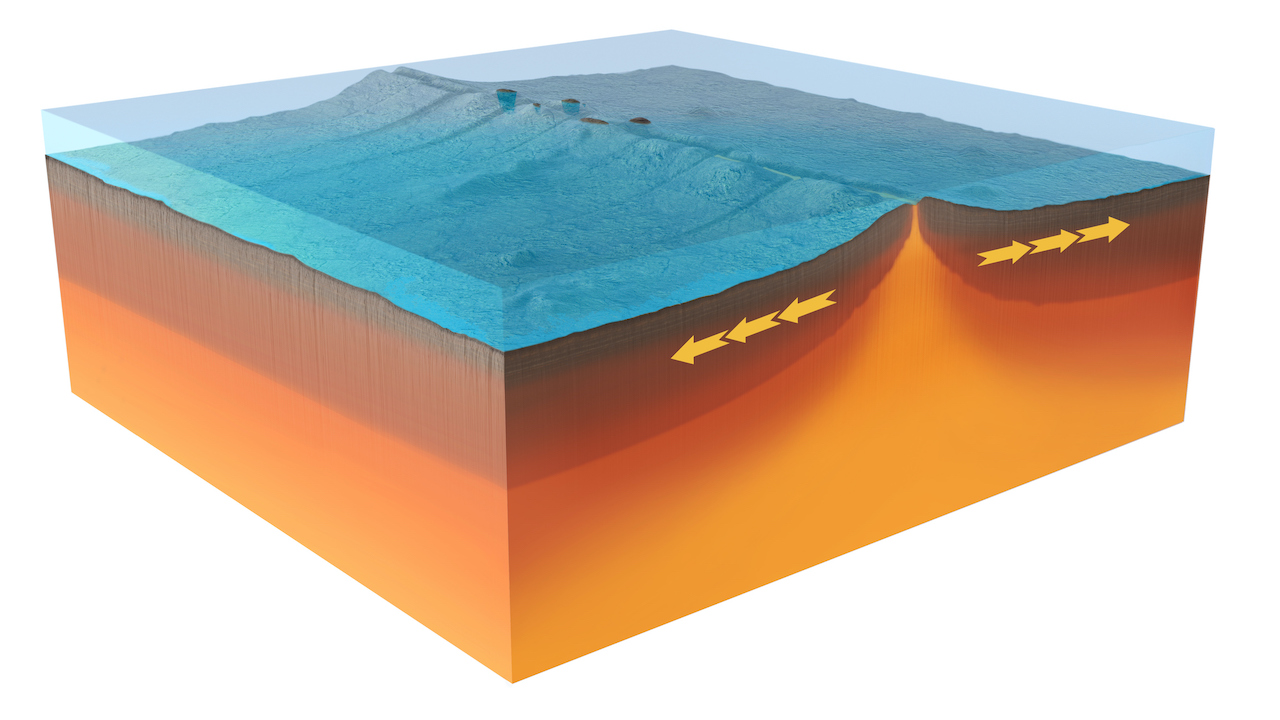

7. The planet is recycled

The ground you're walking on is recycled. Earth's rock cycle transforms igneous rocks to sedimentary rocks to metamorphic rocks and back again.

The cycle isn’t a perfect circle, but the basics work like this: Magma from deep in the Earth emerges and hardens into rock (that's the igneous part). Tectonic processes uplift that rock to the surface, where erosion shaves bits off. These tiny fragments get deposited and buried, and the pressure from above compacts them into sedimentary rocks such as sandstone. If sedimentary rocks get buried even deeper, they "cook" into metamorphic rocks under lots of pressure and heat, according to Dorling Kindersley.

Along the way, of course, sedimentary rocks can be re-eroded or metamorphic rocks re-uplifted. But if metamorphic rocks get caught in a subduction zone where one piece of crust is pushing under another, they may find themselves transformed back into magma.

8. Our moon quakes

Earth's moon looks rather dead and inactive. But in fact, moonquakes, or "earthquakes" on the moon, keep things just a bit shaken up. Quakes on the moon are less common and less intense than those that shake Earth. The total seismic energy released by the moon is about 80 times less than that released by Earth, according to the Encyclopedia of Physical Science and Technology.

According to the Journal of Geophysical Research, moonquakes seem to be related to tidal stresses associated with the varying distance between the Earth and moon. Moonquakes also tend to occur at great depths, about midway between the lunar surface and its center.

9. Chile had the largest earthquake

As of March 2016, the largest earthquake to shake the United States was a magnitude-9.2 temblor that struck Prince William Sound, Alaska, on Good Friday, March 28, 1964.

The world's largest earthquake was a magnitude 9.5 in Bio-Bio, Chile on May 22, 1960, according to the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS).

10. The hottest spot is in Libya

The fiery award for Earth’s hottest spot goes to El Azizia, Libya, where temperature records from weather stations reveal it hit 136 degrees Fahrenheit (57.8 degrees Celsius) on Sept. 13, 1922, according to NASA Earth Observatory. There have likely been hotter locations beyond the network of weather stations.

11. The coldest place is in Antarctica

It may come as no surprise that the coldest place on Earth can be found in Antarctica, but the chill factor is somewhat unbelievable. Winter temperatures there can drop below minus 100 degrees F (minus 73 degrees C).

The lowest temperature ever recorded on Earth came from Russia's Vostok Station, where records show the air plunged to a bone-chilling minus 128.6 degrees F (minus 89.2 degrees C) on July 21,1983, according to the World Meteorological Organization (WMO).

12. Antarctica is an extreme continent

The southern continent is a place of extremes. According to the American Museum of Natural History, the Antarctic ice cap contains some 70 percent of Earth's fresh water and about 90 percent of its ice, even though it is only the fifth largest continent.

Did you know Antarctica is actually considered a desert? Inner regions get just 2 inches (50 millimeters) of precipitation a year (typically as snow, of course).

13. There are giant stalagmites

Spelunkers ahoy! The largest confirmed stalagmite in the world can be found in Cuba in the Cuevo San Martin Infierno, according to the journal Acta Carsologica. This behemoth rises 220 feet (67.2 meters) tall. (Shown here, a photo of a stalagmite in a northwest Yucatan peninsula cave.)

14. There's uneven gravity

Because our globe isn't a perfect sphere, its mass is distributed unevenly. And uneven mass means slightly uneven gravity.

One mysterious gravitational anomaly is in the Hudson Bay of Canada . This area has lower gravity than other regions, and a 2007 study finds that now-melted glaciers are to blame.

The ice that once cloaked the area during the last ice age has long since melted, but the Earth hasn't entirely snapped back from the burden. Since gravity over an area is proportional to the mass atop that region, and the glacier's imprint pushed aside some of the Earth's mass, gravity is a bit less strong in the ice sheet's imprint.

The slight deformation of the crust explains 25 percent to 45 percent of the unusually low gravity; the rest may be explained by a downward drag caused the motion of magma in Earth's mantle (the layer just beneath the crust), researchers reported in the journal Science.

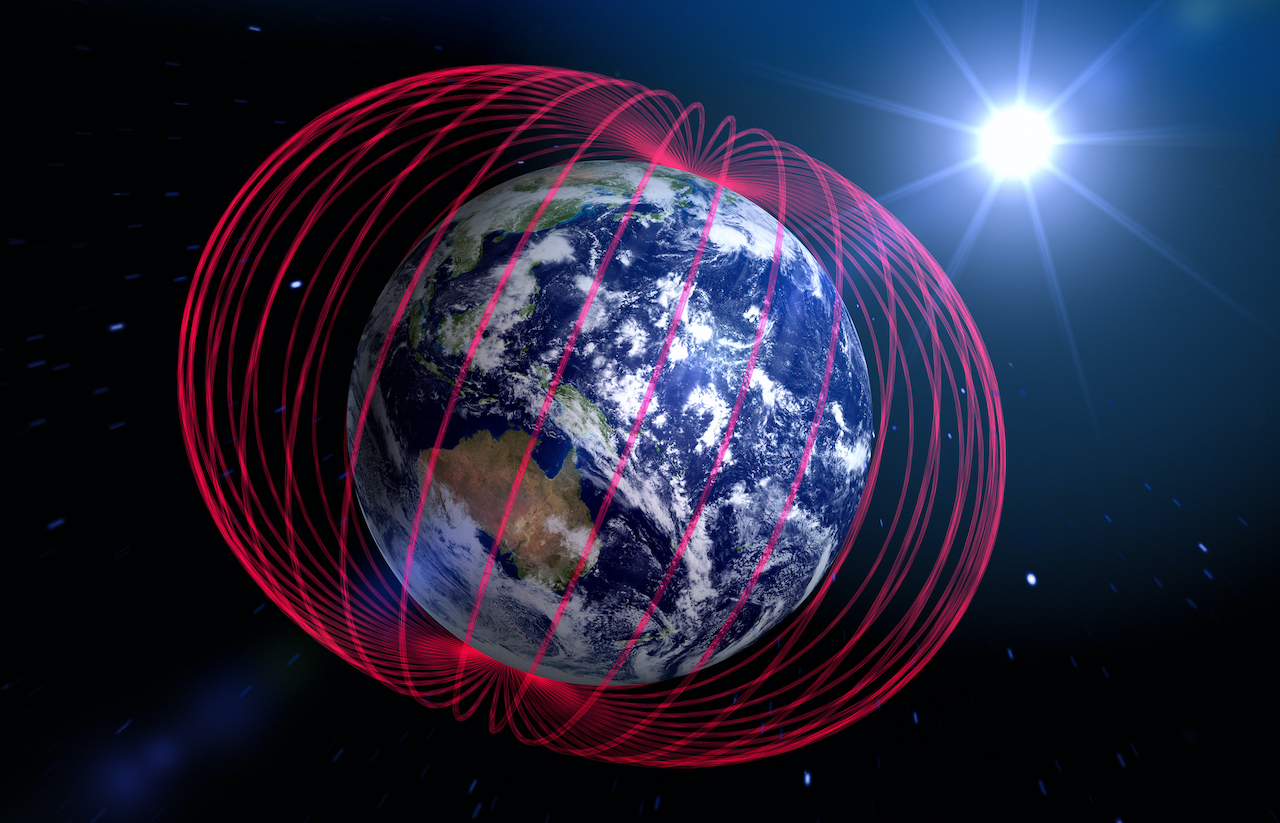

15. The magnetic pole creeps

Earth has a strong magnetic field, similar to a magnet bar, due to the molten iron and nickel in its core, or that's what geophysicists are pretty certain is the cause. This flow of liquid creates electric currents, which, in turn, generate the magnetic field.

Since the early 19th century, Earth's magnetic north pole has been creeping northward by more than 600 miles (1,100 kilometers), according to NASA scientists.

The rate of movement has increased, with the pole migrating northward at about 40 miles (64 km) per year currently, compared with the 10 miles (16 km) per year estimated in the 20th century.

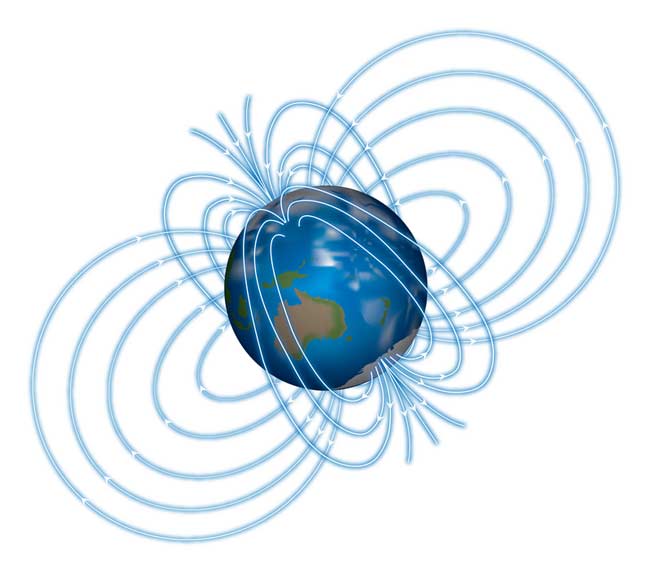

16. The pole flip-flops

In fact, over the past 20 million years, our planet has settled into a pattern of a pole reversal about every 200,000 to 300,000 years, according to the journal Nature. As of 2012, however, it has been more than twice that long since the last reversal.

These reversals aren't split-second flips, and instead occur over hundreds or thousands of years. During this lengthy stint, the magnetic poles start to wander away from the region around the spin poles (the axis around which our planet spins), and eventually end up switched around, according to Cornell University astronomers.

17. There's a tie for tallest mountain

The title for tallest mountain goes to either Mount Everest or Mauna Kea. The summit of Mount Everest is higher above sea level than the summit of any other mountain, extending some 29,029 feet (8,848 meters) high, according to the Indian Journal of History of Science. However, when measured from its true base to summit, Mauna Kea takes the prize, measuring a length of about 56,000 feet (17,170 m), according to the USGS.

Here are some of Mauna Kea's detailed measurements, according to the Hawaii Center for Volcanology: The highest point is 13,680 ft (4,170 m) above sea level; the flanks of Mauna Loa continue another 16,400 ft (5,000 m) below sea level to the seafloor; and the volcano's central portion has depressed the seafloor another 26,000 ft (8,000 m) in the shape of an inverted cone, reflecting the profile of the volcano above it.

18. Earth once had two moons?

Earth may once have had two moons, according to Space.com. A teensy second moon — spanning about 750 miles (1,200 km) wide — may have orbited Earth before it catastrophically slammed into the other one. This titanic clash may explain why the two sides of the surviving lunar satellite are so different from each other, said scientists in the Aug. 4, 2011, issue of the journal Nature.

19. We may still have a second moon?

Some scientists claim Earth still has two moons. According to researchers reporting in the Dec. 20, 2011, issue of the planetary science journal ICARUS, a space rock at least 3.3-feet (1-meter) wide orbits Earth at any given time. They're not always the same rock, but rather an ever-changing cast of "temporary moons," say the scientists.

Their theoretical model posits that our planet's gravity captures asteroids as they pass near us on their way around the sun; when one of these space rocks gets drawn in, it typically makes three irregularly shaped swings around Earth, staying with us for about nine months before hurtling on its way.

20. Rocks can walk

Rocks can walk on Earth, at least they do at the pancake-flat lakebed called Racetrack Playa in Death Valley. There, a perfect storm can move rocks sometimes weighing tens or hundreds of pounds. Most likely, ice-encrusted rocks get inundated by meltwater from the hills above the playa, according to NASA researchers. When everything's nice and slick, a stiff breeze kicks up and moves the rock.

21. People have climbed Everest without oxygen

On May 8, 1978, climbers Reinhold Messner and Peter Habeler became the first to summit Everest without the aid of oxygen, according to the journal Respiratory Physiology and Neurobiology. Messner described his feelings upon reaching the top like this: "I am nothing more than a single narrow gasping lung, floating over the mists and summits."

22. Mid-ocean ridge is the longest mountain chain

To find the world's longest mountain range you'd have to look down, way down. It is called the mid-ocean ridge, and the underwater chain of volcanoes spans some 40,389 miles (65,000 km), according to NOAA. It rises an average of 18,000 feet (5.5 kilometers) above the bottom of the sea.

As lava erupts from the seafloor it creates more crust, adding to the mountain chain, which stretches around the globe.

23. Coral reefs are the largest living structures

Coral reefs support the most species per unit area of any of the planet's ecosystems, rivaling rain forests. And while they are made up of tiny coral polyps, together coral reefs are the largest living structures on Earth — a community of connected organisms — with some visible even from space, according to NOAA.

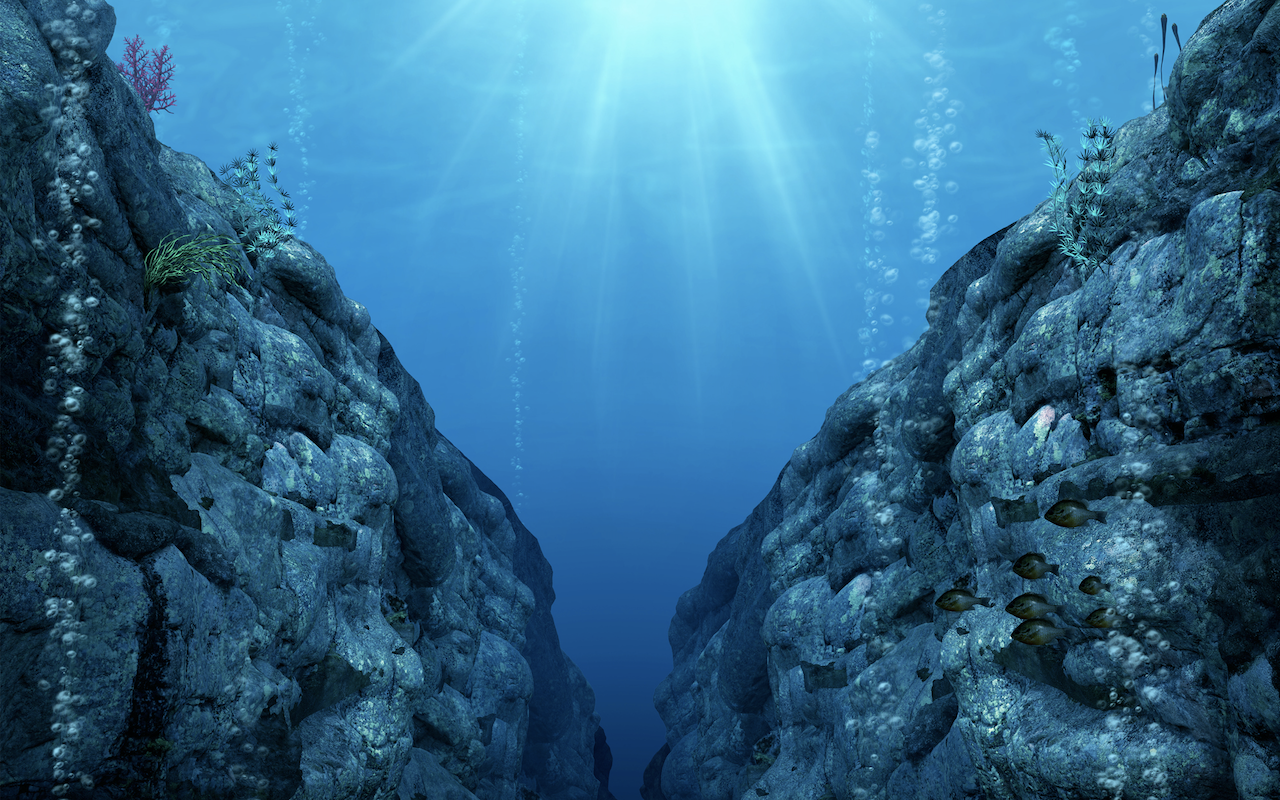

24. The Mariana Trench is the deepest spot

How low can you go? According to NOAA, the deepest point on the ocean floor is 36,200 feet (11,033 meters) below sea level in the Mariana Trench. The lowest point on Earth not covered by ocean is 8,382 feet (2,555) meters below sea level, but good luck walking there: That spot is in the Bentley Subglacial Trench in Antarctica, buried under lots and lots of ice.

25. The Dead Sea is the lowest point on land

The lowest point on land, however, is relatively accessible. It's the Dead Sea between Jordan, Israel and the West Bank, according to the European Space Agency (ESA). The surface of this super-salty lake is 1,400 feet (427 m) below sea level.

26. Lakes can explode

In Cameroon and on the border of Rwanda and the Democratic Republic of the Congo there are three deadly lakes: Nyos, Monoun and Kivu. All three are crater lakes that sit above volcanic earth. Magma below the surface releases carbon dioxide into the lakes, resulting in a deep, carbon dioxide-rich layer right above the lakebed. That carbon dioxide can be released in an explosion, asphyxiating any passersby, according to Nature.

27. We're losing fresh water

As the climate changes, glaciers are retreating and contributing to rising sea levels. It turns out that one particular glacier range is contributing a whopping 10 percent of all the meltwater in the world. That honor belongs to the Canadian Arctic, which lost a volume equivalent to 75 percent of Lake Erie between 2004 and 2009.

28. Glaciers are melting fast

Humans leave our mark on the planet in all sorts of weird ways. For example, nuclear tests in the 1950s threw a dusting of radioactivity into the atmosphere. According to the American Geophysical Union, those radioactive particles eventually fell as rain and snow, and some of that precipitation got trapped in glaciers, where it forms a little "you are here" layer for scientists trying to date the age of glacial ice.

Some glaciers are melting so fast, however, that this half-century of history is gone.

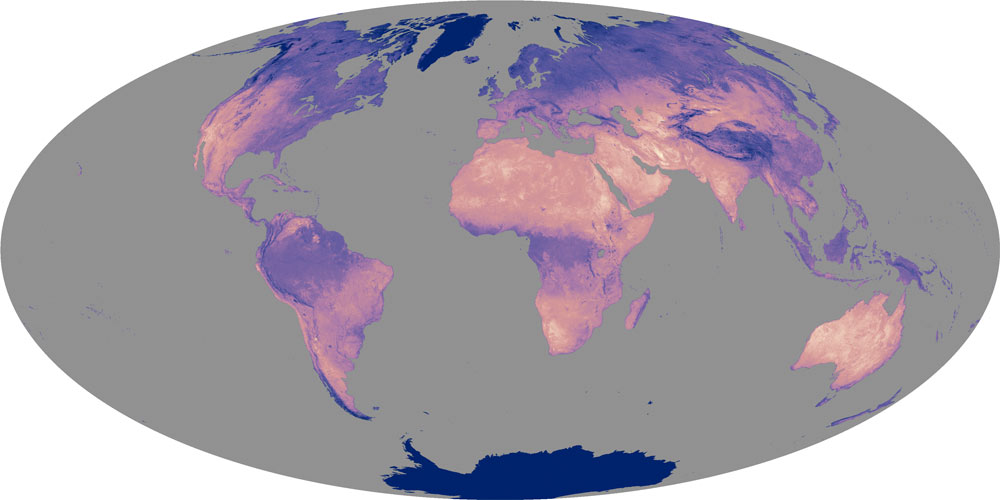

29. Earth used to be purple

It used to be purple … well, life on early Earth may have been just as purple as it is green today, suspects Shil DasSarma, a microbial geneticist at the University of Maryland. Ancient microbes, he said, might have used a molecule other than chlorophyll to harness the sun's rays, one that gave the organisms a violet hue, he suggests.

DasSarma thinks chlorophyll appeared after another light-sensitive molecule called retinal was already present on early Earth. Retinal, today found in the plum-colored membrane of a photosynthetic microbe called halobacteria, absorbs green light and reflects back red and violet light, the combination of which appears purple. The idea may explain why even though the sun transmits most of its energy in the green part of the visible spectrum, chlorophyll absorbs mainly blue and red wavelengths.

30. The planet is electric

Thunder and lightning reveal our planet's fiercer side. A single stroke of lightning can heat the air to around 54,000 degrees Fahrenheit (30,000 degrees Celsius), according to the book Energy by Don Herweck, causing the air to expand rapidly. That ballooning air creates a shock wave and ultimately a boom, better known as thunder.

Bonus fact: Did you know there are about 6,000 lightning flashes around the Earth every minute?

31. Earth is covered in seas

The oceans cover some 70 percent of Earth's surface, according to NOAA, yet humans have only explored or mapped about 20 percent, meaning most of the planet's vast seas have never been seen.

Some 300 million years ago, there was just one continent, a massive supercontinent called Pangaea. This means there was just one giant sea, called Panthalassa.

32. The planet is filled with riches

And these vast seas are rich, holding more than 20 million tons of gold, according to Forbes. But don't grab your mining hat just yet, the metal is so dilute that each liter of seawater contains, on average, about 13 billionths of a gram of gold. Undissolved gold is also tucked away in rocks on the seafloor, and though there's no efficient way of getting at that precious metal, according to NOAA, if we could extract all of it, each person on Earth could have 9 pounds of the shiny stuff.

33. Earth is covered with cosmic dust

Every day our planet is sprinkled with fairy dust … or dust from the heavens. On a daily basis, about 100 tons of interplanetary material (mostly in the form of dust) drifts down to the Earth's surface, according to Astronomy magazine. The tiniest particles are released by comets as their ices vaporize near the sun.

34. We trek around a star

The Earth is approximately 93 million miles (150 million kilometers) from the sun, according to Space.com. At this distance, it takes about 8 minutes and 19 seconds for sunlight to reach our planet.

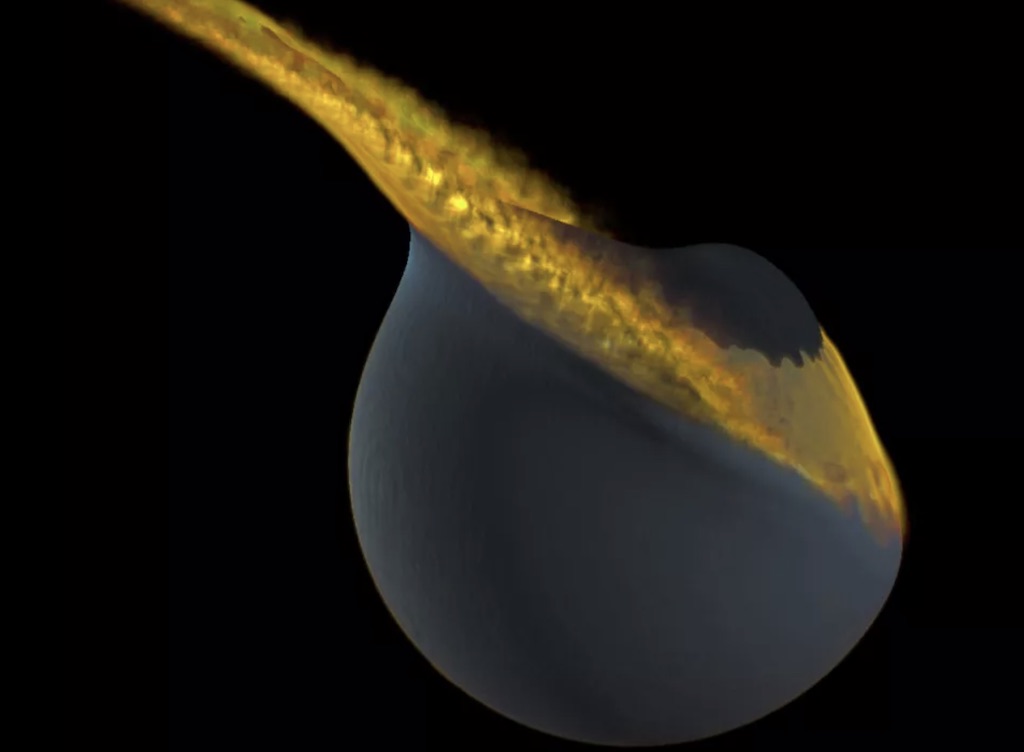

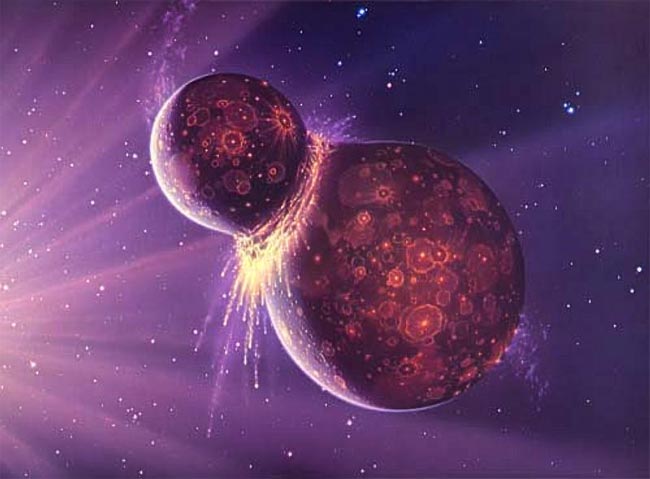

35. Something once collided with the moon

Many researchers think some large object crashed into Earth long ago, and the resulting debris coalesced to form our moon. It is unclear though if that colliding object was a planet, asteroid or comet, with some scientists thinking a Mars-size hypothetical world named Theia was the instigator.

36. There was once a supercontinent

The Earth's continents are thought to have collided to become supercontinents and broken apart again several times in Earth's 4.5 billion year history. The most recent supercontinent was Pangaea, which began to break apart about 200 million years ago; the landmasses that comprised Pangaea eventually wandered into the current configuration of continents.

37. Shifting rocks created mountains

While the shifting slabs of rocks called tectonic plates are unseen to us, some of their effects are monumental. Take the Himalayas, which stretch 1,800 miles (2,900 km) along the border between India and Tibet, according to NASA. This immense mountain range began to form between 40 million and 50 million years ago, when India and Eurasia, driven by plate movement, collided. The tectonic crash led to the jagged Himalayan peaks, according to USGS.

38. Kilauea is not the most active volcano

Kilauea is historically regarded as the most active volcano. But, while Hawaii's Kilauea volcano does pop its top rather frequently, it's not Earth's most active erupter. One that is more active iso the Stromboli Volcano, off the west coast of southern Italy, which has been erupting nearly continuously for over 2,000 years, according to the U.S. Geological Survey. Its spectacular incandescent explosions have earned it the moniker "Lighthouse of the Mediterranean."

39. There was a super-colossal eruption

The largest volcanic eruption recorded by humans occurred in April 1815, the peak of the explosion of Mount Tambora, according to NOAA. The eruption ranked 7 (or "super-colossal") on the Volcanic Explosivity Index (VEI), which goes from 1 to 8 and is somewhat akin to the magnitude scale for earthquakes.

The explosion is said to have been so loud it was heard on Sumatra Island, more than 1,200 miles (1,930 km) away, Live Science previously reported. The death toll from the eruption was estimated at 71,000 people, and clouds of heavy ash descended on many far-away islands.

40. Our coastlines are crowded

Coastlines cover about 20 percent of U.S. land area (not including Alaska), and are home to almost 40 percent of the U.S. population, according to NOAA.

41. The Pacific Ocean is the biggest basin

The Pacific Ocean is by far Earth's largest ocean basin, covering an area of about 63 million square miles (163 million square kilometers) and containing more than half of the free water on Earth, according to NOAA. It's so big that all of the world's continents could fit into the Pacific basin.

42. Trees breathe in oxygen

When we think about big life, whales and elephants come to mind. But try on this tree for size: The General Sherman giant sequoia is the largest known stem tree by volume on the planet. The trunk of the tree contains slightly more than 52,500 cubic feet (1,486.6 cubic meters) of material.

43. A huge fungus is the largest living thing

If you want to pinpoint the biggest organism on the planet, though, your best bet might be a really huge fungus. In 1992, scientists reporting in Nature revealed to the world a Armillaria, or honey mushroom, fungal organism that spans 2,200 acres in Oregon. There’s a slight chance that the offshoots of this mega-fungus aren't clones, but are simply closely related, but we’re in awe either way.

44. This bat is the world's smallest mammal

On the other end of the spectrum, there are plenty of teeny-tiny organisms on Earth, all the way down to single-cell life. But let's focus on something a little more cuddly: the Kitti's hog-nosed bat, also known as the bumblebee bat.

This vulnerable species found in southeast Asia is only about 1 inch (29-33 millimeters) long and weighs only 0.071 ounces (2 grams), putting it in the running with Etruscan shrews– which are lighter but longer– for the world's smallest mammal, according to the Guinness World Records.

45. Tokyo is the most populated city

Don't like crowds? Stay away from Tokyo. This city in Japan is the most densely populated in the world. According to the 2021 World Population Review, , 37,435,191 people live there.

46. Greenland has the most open space

Lovers of solitude might try Greenland on for size. This nation boasts the least population density of any on Earth. As of 2016, 55,847 people lived in 836,330 square miles (2,180,000 square kilometers), according to ScienceNordic. Most of the settlements in Greenland are clustered on the coast, however, so this low population density is somewhat misleading.

47. The Atacama is the driest place on Earth

The driest non-polar desert on Earth is the Atacama Desert of Chile and Peru, according to the journal Antonie van Leeuwenhoek. In the center of this desert, there are places where rain has never been recorded.

48. Roald Amundsen was first to reach the South Pole

Speaking of deserts, the first person to successfully traverse the desert of Antarctica to reach the South Pole was Norwegian Roald Amundsen, according to Royal Museums Greenwich (RMG). He and four other men used sleds pulled by dogs to make it to the Pole. Amundsen would later attribute his success to careful planning.

49. There are other Earth-like planets

There are almost surely more planets like ours. Space scientists have found evidence of Earth-like planets orbiting distant stars, including an alien planet called Kepler 22-b circling in the habitable zone of a star much like ours.

However, Earth is the only planet in the known universe that is confirmed to host life, so whether any of these planets will harbor life is an open question.

50. The skies dazzle with dancing lights

Auroras occur when charged particles from the sun are funneled toward Earth by the planet's magnetic field and collide with the upper atmosphere near the poles, according to RMG. They are more active when the sun's activity peaks during its 11-year solar weather cycle, according to Space.com.

The southern lights, also called aurora australis, are seen less often than aurora borealis, the northern lights, because few people brave Antarctica's dark, freezing winters.

Additional resources

For ten facts about the Earth in space, visit the NASA Science website. Additionally, you can hear about what rivers can tell us about Earth’s history in this TED Talk from geoscientist Liz Hajek.

Bibliography

"On the barometer as an indicator of the earth's rotation and the sun's distance". The London, Edinburgh, and Dublin Philosophical Magazine and Journal of Science (2009).

"Lunar Rocks". Encyclopedia of Physical Science and Technology, Third Edition (2003).

"Constraints on deep moonquake focal mechanisms through analyses of tidal stress". Journal of Geophysical Research E: Planets (2009).

"Regular stalagmites: The theory behind their shape". Acta Carsologica (2008).

"The role of the Earth's mantle in controlling the frequency of geomagnetic reversals". Nature (1999).

"Trigonometrical Survey of India and Naming of Peak XV as Mt. Everest" Indian Journal of History of Science, 50.4 (2015).

"How important is V̇O2max when climbing Mt. Everest (8,849 m)?". Respiratory Physiology & Neurobiology (2022).

"Energy". Herweck, D (2009).

"The fungus Armillaria bulbosa is among the largest and oldest living organisms". Nature (1992).

"Introducing the Atacama Desert". Antonie van Leeuwenhoek (2018).

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus