Archaeopteryx: The Transitional Fossil

Paleontologists view Archaeopteryx as a transitional fossil between dinosaurs and modern birds. With its blend of avian and reptilian features, it was long viewed as the earliest known bird. Discovered in 1860 in Germany, it's sometimes referred to as Urvogel, the German word for "original bird" or "first bird." Recent discoveries, however, have displaced Archaeopteryx from its lofty title.

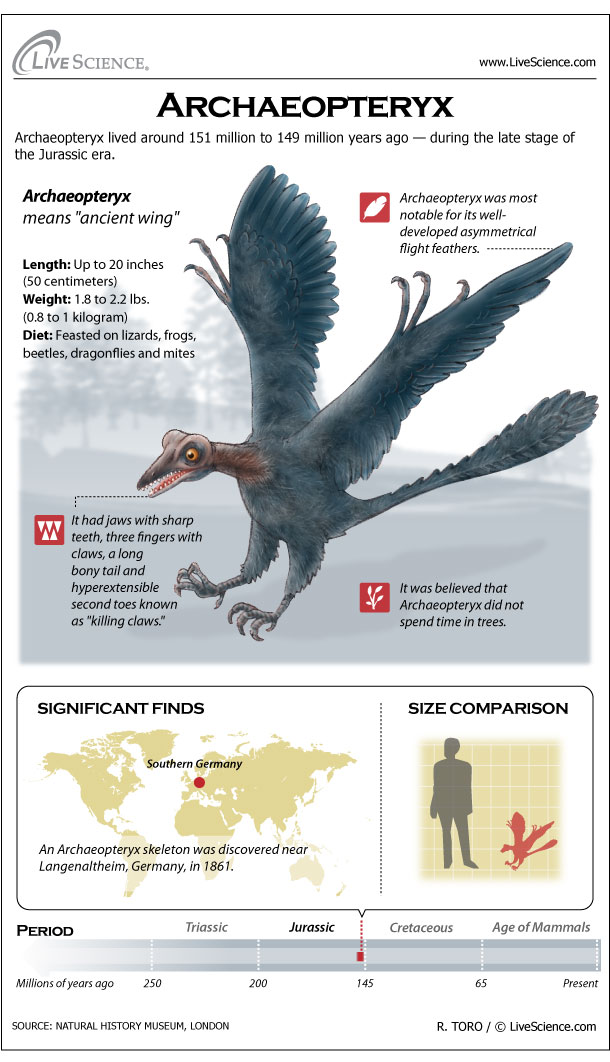

Archaeopteryx is a combination of two ancient Greek words: archaīos, meaning "ancient," and ptéryx, meaning "feather" or "wing." There are two species of Archaeopteryx: A. lithographica and A. siemensii.

Archaeopteryx lived around 150 million years ago — during the early Tithonian stage in the late Jurassic Period — in what is now Bavaria, southern Germany. At the time, Europe was an archipelago and was much closer to the equator than it is today, with latitude similar to Florida, providing this basal bird, or "stem-bird," with a fairly warm — though likely dry — climate.

Could it fly?

Weighing in at 1.8 lbs. to 2.2 lbs. (0.8 to 1 kilogram), Archaeopteryx was about the size of the common raven (Corvus corax), according to a 2009 article in the journal PLOS ONE. It had broad wings with rounded ends and a tail that was long for its body length, which was up to 20 inches (50 centimeters) in total.

Various specimens of Archaeopteryx showed that it had flight and tail feathers, and the well-preserved "Berlin Specimen" showed the animal also had body plumage that included well-developed "trouser" feathers on the legs. Its body plumage was down-like and fluffy like those of the feathered theropod Sinosauropteryx, and may have even been "hair-like proto-feathers" that resemble the fur on mammals, according to a 2004 article in the journal Comptes Rendus Palevol.

Interestingly, the Archaeopteryx specimens found thus far lack any feathering on the upper neck and head, which may be a result of the preservation process.

Based on its wings and feathers, scientists believe Archaeopteryx likely had some aerodynamic abilities.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"The contour feathers in the wing and on the side of the tails of Archaeopteryx have an asymmetric shape, which is usually related to a higher aerodynamic performance," Christian Foth, a paleontologist at the University of Fribourg in Switzerland, told Live Science. "Thus, it is very likely that Archaeopteryx could fly, but it is hard to judge if it was a flapper or a glider."

Archaeopteryx had a primitive shoulder girdle that likely limited its flapping abilities, but it also probably lived in areas without big trees for gliding, and its claw structure suggests it probably didn't climb often or perch on trees. "Therefore, we think that it could perform a simple flapping flight over a very short distance, maybe in relation to hunting or escape behavior," Foth said.

A 2018 study published in the journal Nature Communications also found evidence that Archaeopteryx could fly, although not like any bird alive today does. The researchers used synchrotron microtomography — a tool that uses radiation to make magnified, 3D digital reconstructions of an object — to study the Jurassic creature's fossils. Even though Archaeopteryx didn't have the same features in its shoulders that help modern birds fly, its wings looked like those of modern birds that fly, they found.

"Data analysis furthermore demonstrated that the bones of Archaeopteryx plot closest to those of birds like pheasants that occasionally use active flight to cross barriers or dodge predators, but not to those of gliding and soaring forms such as many birds of prey and some seabirds that are optimized for enduring flight," study co-researcher Emmanuel de Margerie, a researcher at The National Center for Scientific Research (CNRS) in Toulouse, France, said in a statement.

Given that Archaeopteryx is the oldest flying member of the avialan lineage on record, it's likely that "active dinosaurian flight had evolved even earlier," study co-researcher Stanislav Bureš, a researcher at Palacký University in the Czech Republic.

Other research, presented at the 2016 Society of Vertebrate Paleontology meeting in Salt Lake City, found that Archaeopteryx would have been able to fly without running first on the ground, Live Science reported.

In a 2011 study published in the journal Nature Communications, scientists determined that Archaeopteryx's feathers were black. But a new analysis, which was published in 2013 in the Journal of Analytical Atomic Spectrometry and used different methods, suggests the Archaeopteryx's flight feathers had a different coloration, possibly being light (or white) with black tips.

On the other hand, plumage studies of bird-like theropods (predatory dinosaurs) and basal birds suggest the animals had complex color and iridescent patterns, which conceivably were also present in Archaeopteryx. "This indicates that these dinosaurs and basal birds probably already used their plumage for signaling (in relation to species recognition [and] mating) like modern birds," Foth said. "Furthermore, color could be important for camouflage."

In 2014, Foth and his colleagues analyzed the plumage of a new skeletal specimen (the 11th specimen, which is privately owned and yet to be named) and compared it with those of bird-like theropods and other basal birds. Their analysis, published in the journal Nature, showed that contour feathers (outermost feathers that are important for flight) were already present in flightless dinosaurs and that the plumage within different body regions varied widely between species — these findings suggests contour feathers likely initially evolved for brooding, camouflage and display instead of flight.

"In Archaeopteryx, the contour feathers of [the wings] and tail got an additional, aerodynamic function, but secondarily," Foth said.

Despite some of its avian features, Archaeopteryx had more in common with small bird-like theropods (particularly dromaeosaurids and troodontids) than modern birds. These features included jaws with sharp teeth, three fingers with claws, a long bony tail, hyperextensible second toes ("killing claws") and various other skeletal characteristics.

What did Archaeopteryx eat?

Not much is known about Archaeopteryx's diet. However, it was a carnivore and may have eaten small reptiles, amphibians, mammals, and insects.

It likely seized small prey with just its jaws, and may have used its claws to help pin larger prey.

Fossil finds

Archaeopteryx was first discovered in 1860 or 1861, when a solitary feather was unearthed from limestone deposits near Solnhofen, Germany. This feather, however, may have come from another, undiscovered proto-bird.

In 1861, the first Archaeopteryx skeleton, which was missing most of its head and neck, was unearthed near Langenaltheim, Germany. As a form of payment, it was given to a doctor, who later sold it to the London Natural History Museum. The discovery coincided with the publication of Darwin's "On the Origin of Species," and the specimen, dubbed the London Specimen, seemed to confirm his theories.

Archaeopteryx has since become central to the understanding of evolution.

The most complete skeleton, the Berlin Specimen, was discovered in 1874 or 1875 near Eichstatt, Germany by farmer Jakob Niemeyer, who sold it in 1876 to innkeeper Johann Dörr. Through various transactions, the fossil, which is the first found to have an intact head, eventually wound up being in the Humboldt Museum fur Naturkunde, where it still resides.

Other specimens include, among others, the Maxberg Specimen, Eichstätt Specimen, and Haarlem Specimen, which was originally classified as a Pterodactylus species.

The 12th and last Archaeopteryx specimen to be found was discovered in 2010 and announced in 2014, but hasn't yet been scientifically described.

Dethroned as first bird

Recent discoveries from China, Mongolia and Argentina have shaken up what paleontologists knew about the relationship between stem-birds and bird-like theropods.

In 2011, scientists uncovered a fossil in Liaoning, China, whose combination of features unexpectedly suggested Archaeopteryx was actually just a relative of the lineage that ultimately gave rise to birds

When the researchers analyzed features of the new specimen, Xiaotingia zhengi, and Archaeopteryx, they concluded that both animals belonged to the dinosaur group Deinonychosauria — bird-like theropods, which includes Velociraptor and Microraptor — instead of the stem-bird group Avialae.

The analysis, published in Nature, also suggested the earliest known avialan is a pigeon-size feathered creature known as Epidexipteryx hui, recently discovered in Inner Mongolia, China.

However, subsequent analyses (including Foth's 2014 study) of Archaeopteryx, Xiaotingia and other creatures, such as Aurornis and Anchiornis, have restored Archaeopteryx to its Avialae roots.

"Here, Archaeopteryx turned out to be a basal bird, again," Foth said. "Interestingly, we also found Anchiornis and Xiaotingia on the stem-bird branch, even more basal than Archaeopteryx. Per definition, these guys would [now] be the oldest representatives of stem-birds, but Archaeopteryx would be the first definitely fightable representative."

Additional reporting by Live Science Contributor Kim Ann Zimmermann and Live Science Senior Writer Laura Geggel.

Related pages

More dinosaurs

- Allosaurus: Facts About the 'Different Lizard'

- Ankylosaurus: Facts About the Armored Dinosaur

- Apatosaurus: Facts About the 'Deceptive Lizard'

- Brachiosaurus: Facts About the Giraffe-like Dinosaur

- Diplodocus: Facts About the Longest Dinosaur

- Giganotosaurus: Facts about the 'Giant Southern Lizard'

- Pterodactyl, Pteranodon & Other Flying 'Dinosaurs'

- Spinosaurus: The Largest Carnivorous Dinosaur

- Stegosaurus: Bony Plates & Tiny Brain

- Triceratops: Facts about the Three-horned Dinosaur

- Tyrannosaurus Rex: Facts about T. Rex, King of the Dinosaurs

- Velociraptor: Facts about the 'Speedy Thief'

Time periods

Precambrian: Facts About the Beginning of Time

Paleozoic Era: Facts & Information

- Cambrian Period: Facts & Information

- Silurian Period Facts: Climate, Animals & Plants

- Devonian Period: Climate, Animals & Plants

- Permian Period: Climate, Animals & Plants

Mesozoic Era: Age of the Dinosaurs

- Triassic Period Facts: Climate, Animals & Plants

- Jurassic Period Facts

- Cretaceous Period: Facts About Animals, Plants & Climate

Cenozoic Era: Facts About Climate, Animals & Plants

Additional resources

- University of California Museum of Paleontology: Archaeopteryx: An Early Bird

- UK Natural History Museum: Archaeopteryx fossil