Reptiles evolved earlier than we thought, newly discovered claw-mark fossils suggest

New fossilized tracks made by an ancient reptile indicate that these animals evolved tens of millions of years sooner than scientists first thought.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Reptiles as we know them today may have evolved about 30 million years earlier than we initially assumed, new footprints reveal.

According to a study published Wednesday (May 14) in the journal Nature, fossilized tracks found in Australia may have been left by the clawed feet of a small reptile-like creature about 350 million years ago, during the Carboniferous period.

This new discovery would push back the evolution of these animals by roughly 30 million years, as early reptiles were previously thought to have evolved around 320 million years ago.

"Once we identified this, we realised this is the oldest evidence in the world of reptile-like animals walking around on land — and it pushes their evolution back by 35-to-40 million years older than the previous records in the Northern Hemisphere," study co-author John Long, a strategic professor of palaeontology at Flinders University in Australia, said in a statement.

"The implications of this discovery for the early evolution of tetrapods are profound."

Modern reptiles, along with birds and mammals, are part of a group of animals known as amniotes, which are defined as tetrapod vertebrates (four-limbed animals with backbones) that lay eggs equipped with a protective membrane that surrounds the embryo. This so-called amnion allows eggs to be laid on land, freeing early land animals from dependency on water for reproduction. This is in contrast to amphibians, which rely on moist environments to reproduce.

Related: Which animal species has existed the longest?

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Amniotes evolved from amphibian-like ancestors, with the earliest amniote body fossils being dated to the late Carboniferous Period, which spanned from approximately 359 to 299 million years ago. These early amniotes, which were small, lizard-like creatures, then diversified into two groups: synapsids and sauropsids, which evolved into the earliest ancestors of mammals and reptiles, respectively.

Based on the fossil record, amniotes were thought to have evolved around 320 million years ago. However, this new discovery of clawed amniote footprints in Australia from 350 million years ago throws these estimations hugely off.

"I'm stunned," study co-author Per Ahlberg, a professor of paleontology at Uppsala University, said in a statement. "A single track-bearing slab, which one person can lift, calls into question everything we thought we knew about when modern tetrapods evolved."

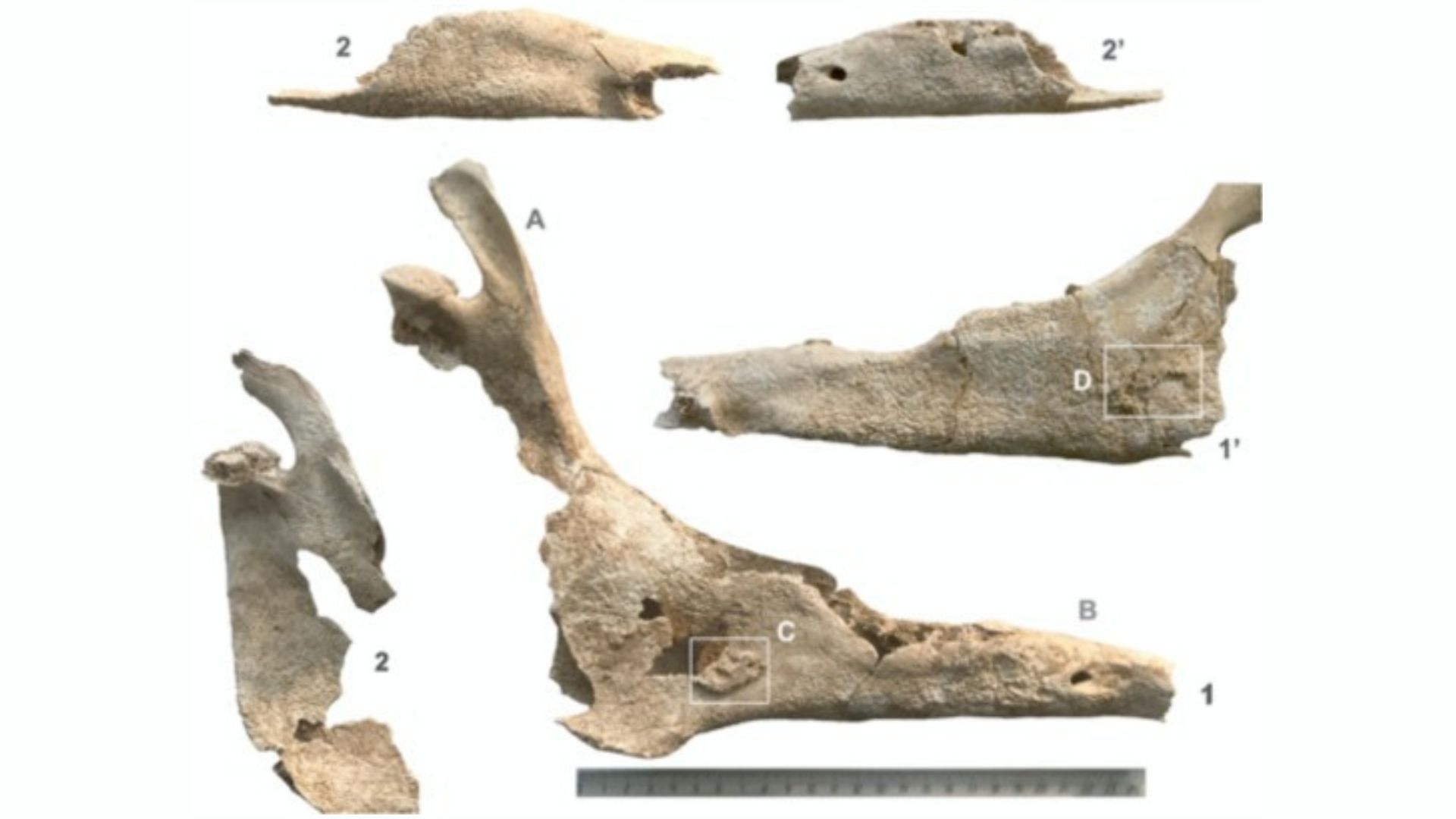

These footprints were discovered on a 20-inch (50cm) rock slab by two amateur palaeontologists in the Snowy Plains Formation in Australia's Victoria, which dates back to 350 million years ago. The footprints appeared to have been made by a creature with clawed feet and long toes, likely an early sauropsid, meaning that reptiles may have been around much earlier than we assumed.

"Claws are present in all early amniotes, but almost never in other groups of tetrapods," Ahlberg said. "The combination of the claw scratches and the shape of the feet suggests that the track maker was a primitive reptile."

These footprints are the earliest clawed prints ever discovered.

"When I saw this specimen for the first time, I was very surprised," study co-author Grzegorz Niedźwiedzki, a researcher at Uppsala University, said in the statement.

Pushing back the tree of reptilian evolution, the researchers concluded that reptiles may have actually evolved towards the end of the Devonian period, when primitive fish-like creatures like Tiktaalik roamed the land.

"It's all about the relative length of different branches in the tree," Ahlberg said. "In a family tree based on DNA data from living animals, branches will have different lengths reflecting the number of genetic changes along each branch segment. This does not depend on fossils, so it's really helpful for studying phases of evolution with a poor fossil record."

Niedźwiedzki added: "The most interesting discoveries are yet to come and that there is still much to be found in the field. These footprints from Australia are just one example of this."

Jess Thomson is a freelance journalist. She previously worked as a science reporter for Newsweek, and has also written for publications including VICE, The Guardian, The Cut, and Inverse. Jess holds a Biological Sciences degree from the University of Oxford, where she specialised in animal behavior and ecology.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus