Could Dinosaurs Fly?

Some dinosaurs may not have been restricted to life on the ground and instead could have launched into the air for quick flights, researchers have found.

As long as the creature's wing size, weight and muscles met certain criteria, it could likely fly. But these feathery creatures would be no match for today's birds, which can fly long distances.

"They probably could not sustain flight for long or go very far," said study lead researcher Michael Habib, an assistant professor of cell and neurobiology at the University of Southern California. [Images: Dinosaurs That Learned to Fly]

Feathery dimensions

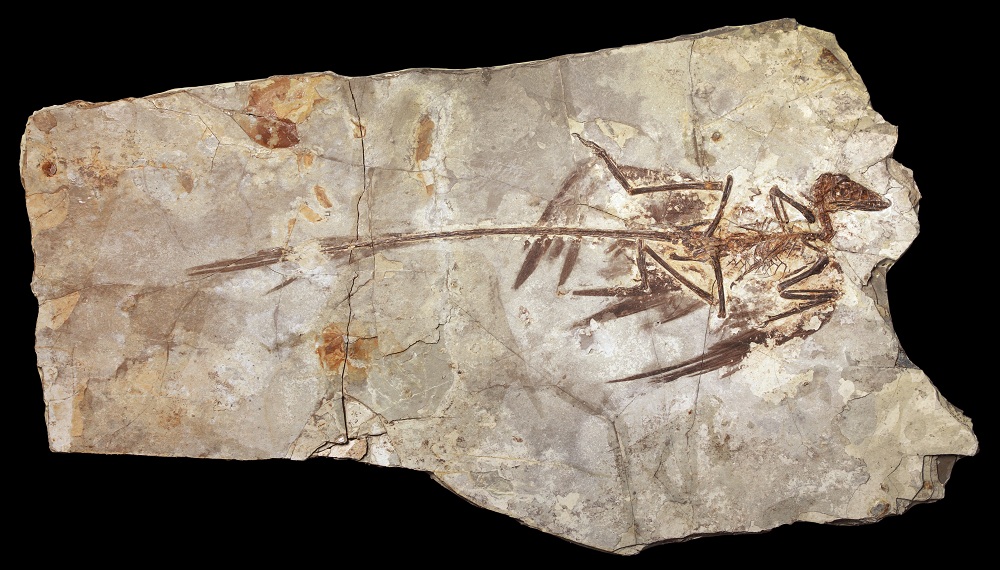

Birds are the descendants of theropods — dinosaurs that walked on two legs and mostly ate meat, including Velociraptor and Tyrannosaurus rex. Many small theropods sported feathered arms, as did early birds that lived during the dinosaur age, Habib said. But despite the vast fossil record, it was unclear whether these creatures could fly, he said.

To investigate, Habib and his colleagues examined 51 fossilized specimens from 37 bird-like dinosaurs and early bird genuses (also known as genera) that lived before the asteroid smashed into Earth 65.5 million years ago.

The analysis revealed that the bird-like dinosaurs Microraptor, Rahonavis (which is sometimes referred to as an early bird), and five avian genuses — Archaeopteryx, Sapeornis, Jeholornis, Eoconfuciusornis and Confuciusornis — would have been able to launch from the ground (without running) and initiate flight.

The researchers also looked at fossils representing different stages of life to see if molting and egg retention would have affected takeoff and flight.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"Of the [latter] two, molting shows the most significant effects," the researchers wrote in their abstract. "Reducing the wing area via molting would make takeoff in Microraptor difficult, though not impossible."

Flying metrics

Powerful leg muscles, big wings and a relatively small body size were instrumental for takeoff and flight in ancient birds and bird-like dinosaurs, but big flight muscles were not as critical, Habib said.

Body weight and wing size figure into a metric called "wing loading," or the ratio of body mass to wing area, the researchers found.

"In living, flying birds, for every 2.5 grams of body mass, you need at least 1 square centimeter of wing [0.6 ounces of mass per square inches of wing]," in order to both lift off the ground and remain airborne for any time, Habib told Live Science. High-speed flying birds must be lighter — probably closer to 2 grams per square centimeters (0.5 ounces per square inch of wing area), he said.

Moreover, leg muscles helped with takeoff, as did flight muscles, though to a lesser extent, Habib said.

"You don't need a lot of flight muscle [for liftoff and flight]," he said. "You need a lot of flight muscle to do the really acrobatic, really sophisticated stuff, like if you're going to take off from the ground and launch straight up." But a bird-like dinosaur or early bird didn't need extraordinarily powerful flight muscles to flap up to reach a tree branch, he said.

"So much more power comes from the hind limb to begin with," Habib said. "The flight muscle power really only comes into play at the end of that, in terms of how steeply you can take off or how far you can fly." [Photos: Birds Evolved from Dinosaurs, Museum Exhibit Shows]

No trees needed

In addition, the researchers found that it's unlikely that birds began flying by falling out of trees, he said.

"No flying animal alive today actually takes off that way," Habib said. "Not one."

He explained that neither animals nor planes launch by falling. "The reason is pretty simple: From a physics standpoint, that would be a really awful way to take off, because you're accelerating one gravity down [which is is 9.8 meters per second squared, or about 32 feet per second squared], and you want to be accelerating two, preferably three gravity up," Habib said.

However, it's impossible to say for certain whether trees were part of early flight, he said.

"What we can say is that you don't have to have trees involved," he said.

The study, which has yet to be published in a peer-reviewed journal, was presented in October at the 2016 Society of Vertebrate Paleontology meeting in Salt Lake City.

Original article on Live Science.

Laura is the managing editor at Live Science. She also runs the archaeology section and the Life's Little Mysteries series. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus