Human eggs have special protection against certain types of aging, study hints

A new study suggests that the mitochondria in human egg cells don't accumulate DNA mutations with age, which sets them apart from other tissues in the body.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

A new study suggests that human egg cells may be protected against certain age-driven changes seen across the rest of the body.

The work, published Aug. 6 in the journal Science Advances, didn't explore how that protection works, but it did highlight a stark difference between the mitochondria — cellular powerhouses — found in adult women's blood and saliva and those carried in their eggs. Mitochondria carry their own special DNA, and as the body ages, that DNA mutates. But there seems to be an exception to this rule within the mitochondria in human egg cells.

Mutations in mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) aren't always harmful, but in some cases, they can cause diseases that affect the body's ability to make and use energy. These conditions can be life-threatening. There are no approved cures, and treatments typically focus on easing symptoms rather than on correcting the underlying issue. As such, it's important to understand whether the mitochondria in eggs pick up more mutations as they age, as that could raise the risk of such diseases in children.

This could potentially be a factor to consider in family planning. For instance, if the risk of disease-causing mitochondrial mutations were extremely high in older eggs, it might be an argument for freezing one's eggs at younger ages, study co-author Barbara Arbeithuber, a research group leader at Johannes Kepler University Linz in Austria, told Live Science in an email.

Still, mitochondria are not the only factor to consider in egg quality as it's known that egg cells decline in other ways as they age. And importantly, this new study "does not directly tell us anything on reproductive interventions, as those were not the focus of our work," Arbeithuber said.

"It is premature to apply these findings to clinical practice," said study co-author Kateryna Makova, a professor of biology at Penn State. "Our results should be replicated in a larger number of women and validated in other human populations," Makova told Live Science in an email.

Related: 8-year-old with rare, fatal disease shows dramatic improvement on experimental treatment

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Eggs partly "protected" from aging

Studies suggest that, at older ages, egg cells do pick up new mutations in their chromosomes, the DNA found in the cells' nucleus. There's evidence that older oocytes, or egg cells, are less able to repair DNA damage than younger oocytes are. Additionally, pregnancies that occur at maternal ages of 35 and older are associated with a higher rate of chromosomal abnormalities than pregnancies at younger ages. That's partly due to changes in the eggs that make them more likely to have an abnormal number of chromosomes when they reach maturity.

(Notably, advanced paternal age also drives up the rate of genetic abnormalities in offspring, so sperm cells — not just eggs — also contribute to that mutational burden.)

But while the effect of aging on chromosomal DNA in eggs and sperm is fairly well studied, scientists' understanding of what happens to the DNA in an egg's mitochondria as it ages is less clear.

"For human oocytes, previous reports were controversial," Arbeithuber said. The methods used to analyze DNA in those prior studies weren't accurate enough to pin down the true rate of mitochondrial mutations. Arbeithuber and her colleagues instead used an approach called duplex sequencing, which has a much lower error rate.

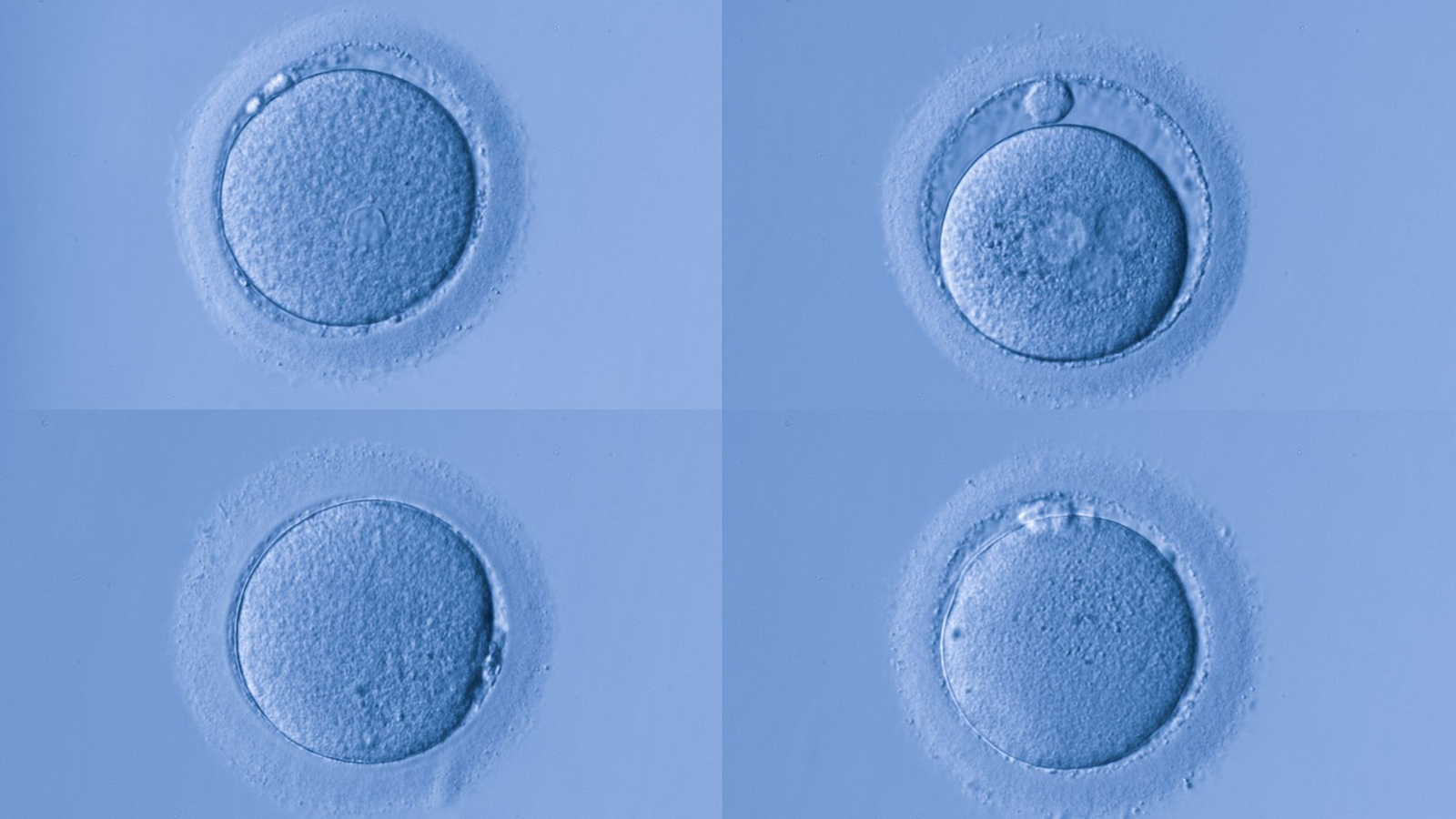

For the study, they recruited 22 women ages 20 to 42 who were undergoing in vitro fertilization (IVF). For each participant, they analyzed blood and saliva samples, as well as one to five oocytes. In total, they assessed 80 egg cells across the 22 women.

Across all of the blood, spit and egg samples, the eggs' mitochondria had 17- to 24-fold fewer mutations than those in the blood and saliva. And that comparatively low rate of mutations stayed steady. The number of mutations seen in blood increased the most across the age groups, followed by saliva, and there was no statistically significant increase in the number of mutations in the eggs.

When the team zoomed in on the few mutations that did appear in the eggs, they found that they were less likely to impact DNA previously tied to diseases than the mutations seen in blood and saliva.

"The good news is that, unlike what happens in other tissues of the body such as blood or saliva … human oocytes do not accumulate more mutations as women age, at least between 20 and 42," Filippo Zambelli, a lead consultant at the reproductive medicine service TRT Consultancy in Barcelona, Spain, told the Science Media Centre. "This suggests that mtDNA in oocytes is protected against aging and its potential negative impact on cellular function," said Zambelli, who was not involved in the research.

"Overall, this study is reassuring for people trying to conceive children at later ages, because, although chromosomal abnormalities increase with maternal age, at least they should not expect a higher level of mutations in their mtDNA," he said. Notably, though, this study included only 22 people, so the results bear confirmation in larger studies, he added.

Next steps

Prior to the new study, the same researchers had investigated mitochondrial mutations in mice and monkeys. In mice, they observed an increase in mtDNA mutations with age in both egg cells and other body tissues, like muscle. In monkeys, they found that mutations increased in eggs and other tissues until the primates reached about 9 years old — equivalent to roughly 27 years old in human years. At that point, the egg mutation rate plateaued while other body parts accumulated more and more DNA changes.

"It is possible that this is also the case in humans," Arbeithuber suggested, meaning it may be that eggs accumulate some mitochondrial mutations in earlier life and then stop at a certain point.

Their new study was somewhat limited in that they obtained eggs from people undergoing IVF, so "we were restricted by the age of individuals who consult such a clinic," she added. In the future, it could be interesting to analyze eggs from younger age groups and across generations, from mothers to children, she said.

At this point, the researchers don't know how mitochondrial DNA in eggs remains preserved over time while other tissues mutate. "This is an open question," Arbeithuber said. In their paper, the team proposed that there may be a process that helps to eliminate harmful mutations from the oocyte DNA, but more research will be needed to confirm this idea.

This article is for informational purposes only and is not meant to offer medical advice.

Nicoletta Lanese is the health channel editor at Live Science and was previously a news editor and staff writer at the site. She holds a graduate certificate in science communication from UC Santa Cruz and degrees in neuroscience and dance from the University of Florida. Her work has appeared in The Scientist, Science News, the Mercury News, Mongabay and Stanford Medicine Magazine, among other outlets. Based in NYC, she also remains heavily involved in dance and performs in local choreographers' work.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus