Apatosaurus: Facts About the 'Deceptive Lizard'

While some people outside the scientific community still refer to Apatosaurus as Brontosaurus, the name Brontosaurus was actually the result of a fossil mix-up.

American paleontologist Othniel C. Marsh named one of his fossil discoveries — an incomplete set of the remains of a juvenile dinosaur — Apatosaurus ajax in 1877. Two years later, in 1879, he discovered another sauropod (dinosaurs best known for their incredibly long necks) specimen that was larger and more complete. Marsh believed the new find represented an entirely different genus of dinosaur, and decided to name it Brontosaurus excelsus.

In 1903, paleontologist Elmer Riggs re-examined Marsh's fossils and concluded that they were similar enough to belong to the same genus (most paleontologists today support his conclusions). According to naming conventions, the older name takes precedence, meaning that Brontosaurus excelsus should actually be Apatosaurus excelsus. However, Riggs published his examination in a relatively obscure journal, so his findings were largely unknown to people at the time. Additionally, by this time, the name Brontosaurus had gained a lot of public exposure by various non-scientific places, such as the Sinclair oil company, which used the animal as its logo, according to paleontologist Michael Taylor.

Today, Brontosaurus is still a well-known moniker and remained in popular use until a few decades ago. The Flintstones' pet dinosaur, Dino, was described as a Brontosaurus. Fred Flintstone was also known to eat Bronto-burgers. The U.S. Postal Service even used the name in 1989 when it issued a series of dinosaur stamps, contending that the name was more familiar to the general public than Apatosaurus, according to the New York Times.

And still, the naming controversy continues. A 2015 study suggested that there are enough differences between two Apatosaurus specimens that one of them should be in a different genus and reclassified Brontosaurus.

Anatomy of a giant

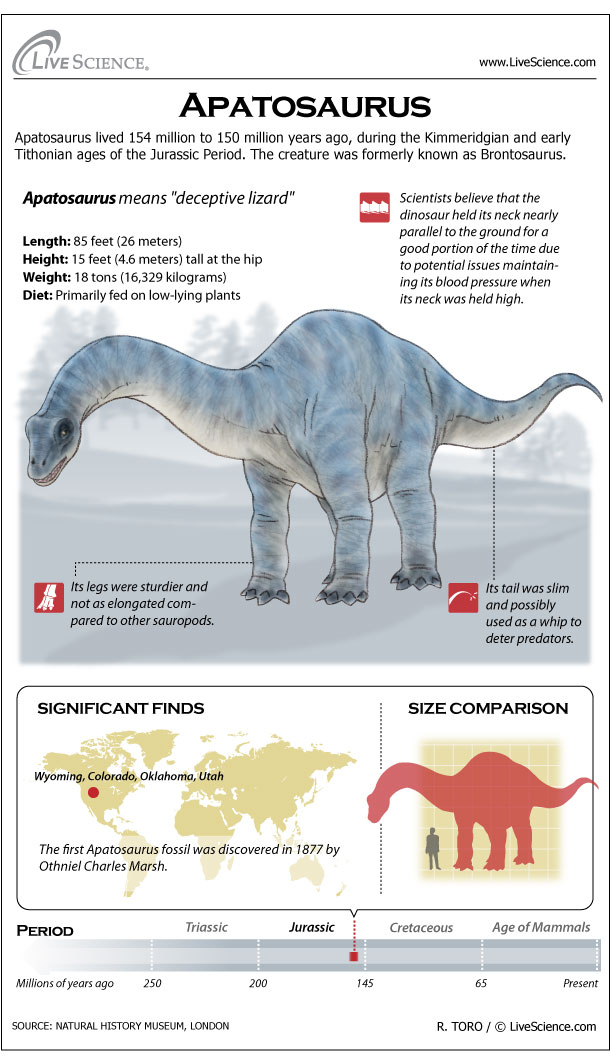

Apatosaurus was an herbivorous sauropod dinosaur that lived from about 155.7 to 150.8 million years ago, during the Kimmeridgian and early Tithonian ages of the Jurassic Period. The term Apatosaurus comes from the Greek words apate/apatelos, meaning "deceptive," and sauro, meaning "lizard." Marsh gave it this name because some of its bones resembled those of some mosasaurs, a type of large aquatic reptile.

It's believed to be one of the biggest land animals to have roamed the Earth. Fossils of A. louisae (the largest known Apatosaurus species) suggest the dinosaur reached 68.9 to 74.8 feet (21 to 22.8 meters) in length. In the past, Apatosaurus was estimated to weigh up to 39 tons (35 metric tons, or 35,000 kilograms), but modern modeling techniques puts its average weight closer to 19.8 tons (18 metric tons), according to a 2009 study in the Journal of Zoology.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

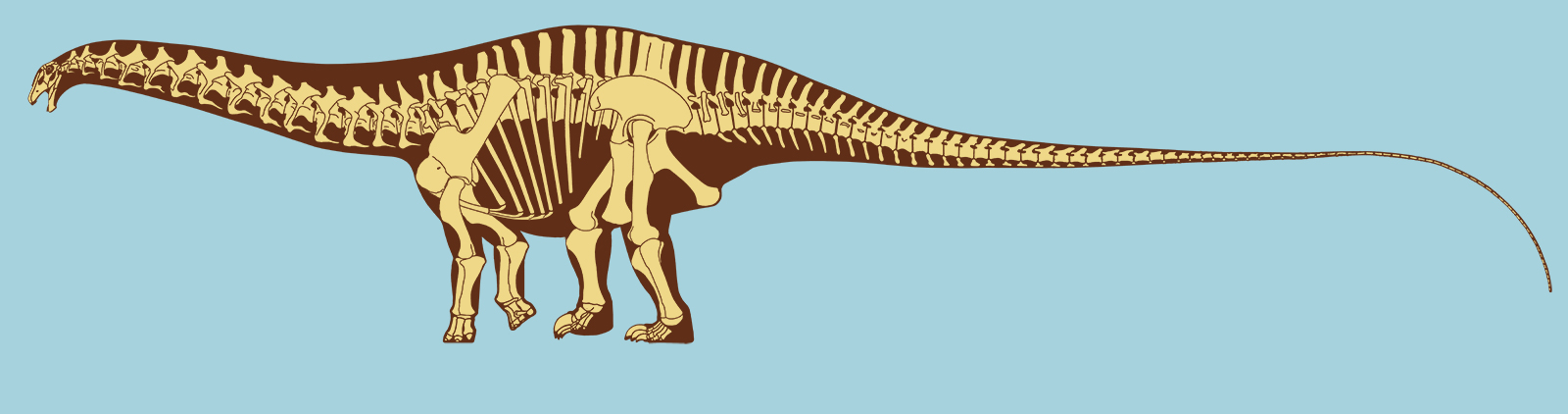

Like other sauropods, the vertebrae were made up of paired spines, producing a very wide and thick neck. But its neck was not as heavy as it might have been, thanks to a system of air sacs that kept it relatively light for its size.

The neck posture and neck flexibility of Apatosaurus and other sauropods is highly debated. Computer models in the 1990s suggested that Apatosaurus had little neck flexibility and probably held its head horizontally (it wouldn’t have been able to eat from the tops of trees and then bend its head all the way down to the ground to drink water). But based on comparisons with animals alive today, Apatosaurus may have held its head high with a swan-like S-curve to its flexible neck, a 2009 study in the journal Acta Palaeontologica Polonica argued.

However, a 2013 study in the journal PLOS ONE looked at the neck flexibility of ostriches (the closest long-neck sauropod relative), and concluded that previous neck-flexibility models, which don't take into account the effect of soft tissues, cannot truly estimate the flexibility of sauropod necks — what this means for the actual posture and flexibility of Apatosaurus necks is unclear.

Apatosaurus had legs that were sturdier and not as elongated as other sauropods, such as Brachiosaurus, and its hind limbs were larger than its forelimbs. Like most sauropods, Apatosaurus had only a single large claw on each forelimb, with the first three toes on the hind limb possessing claws.

Its tail was long and unusually slim, resembling a bullwhip. A computer model detailed in a 1997 Discover magazine article found that the crack of the tail tip would have produced a "cannonlike boom" heard for miles. However, the slender tip of Apatosaurus' tail would probably be unable to hurt any predators, negating its use as a weapon.

Apatosaurus, like its close relative Supersaurus, had unusually tall spines on its vertebrae, which make up more than half the height of the individual bones.

The vertebral spines rapidly decrease in height the farther they are from the hips, giving the tail its slender shape.

Apatosaurus had a skull that was rather small for its body size. It contained chisel-like teeth, suited to an herbivorous diet.

What did Apatosaurus eat?

It's believed that Apatosaurus primarily fed on low-lying plants, but its long neck may have enabled this sauropod to eat soft leaves on higher trees, if its neck was flexible enough. Apatosaurus likely swallowed large chunks of plants without chewing and ingested stones to help with digestion. Like other large sauropods, Apatosaurus probably had to eat up to 400 kilograms (880 pounds) of food every day to survive, according to a 2008 study in the Proceeding of the Royal Society B.

In the early 2000s, some scientists suggested Apatosaurus and other large sauropods got to be so huge because of their food supply. That is, their food was so low in nitrogen — which is necessary for protein formation and energy — that they had to eat a lot of it to survive, increasing their body size. Subsequent research, which analyzed the total energy in modern plants, discarded this idea.

"But the idea isn't based on energy, it's based on carbon-to-nitrogen ratios," Wilkinson told LiveScience. In a 2012 study in the journal Functional Ecology, Wilkinson and his colleagues took another look at the theory, and concluded that it shouldn't be written off just yet. "Our key point is that the idea is still a contender. "

However, some research suggests other factors may have been more important in driving up sauropods' body sizes, such as swallowing large amounts of food without chewing.

Dinosaur farts

Like the big herbivores of today, Apatosaurus probably relied on gut microbes to help them digest plant matter, resulting in the production of the greenhouse gas methane. In a 2012 study in the journal Current Biology, researchers calculated that Apatosaurus and other sauropods produced about 520 million tons of methane per year, which is not so different from the amount of methane currently produced by both natural and manmade sources.

"They produced enough methane to have a minor but measurable effect on the global climate," said study lead researcher David Wilkinson, a biologist at Liverpool John Moores University in the United Kingdom. "In theory, they could have produced enough methane to play a role in sustaining the warm climate of the Mesozoic era."

Fossil finds

Apatosaurus fossils have been unearthed in Nine Mile Quarry and Bone Cabin Quarry in Wyoming as well as in areas of Colorado, Oklahoma and Utah.

Apatosaurus louisae was named by William Holland in 1915 in honor of Louise Carnegie, wife of Andrew Carnegie who funded field research to find complete dinosaur skeletons in the American West. Apatosaurus louisae is known from one nearly complete skeleton, which was found in Utah.

In 2008, footprints of a juvenile Apatosaurus were found in Quarry Five in Morrison, Colo. Discovered by Matthew Mossbrucker, these footprints indicated that juveniles could run on their hind legs, according to Smithsonian Magazine.

In 2013, Mossbrucker identified the first A. ajax snout ever discovered, which may help paleontologists better understand how the dinosaur is related to other sauropods.

Additional reporting by Kim Ann Zimmermann, Live Science Contributor

Related pages

More dinosaurs

- Allosaurus: Facts About the 'Different Lizard'

- Ankylosaurus: Facts About the Armored Dinosaur

- Archaeopteryx: Facts about the Transitional Fossil

- Brachiosaurus: Facts About the Giraffe-like Dinosaur

- Diplodocus: Facts About the Longest Dinosaur

- Giganotosaurus: Facts about the 'Giant Southern Lizard'

- Pterodactyl, Pteranodon & Other Flying 'Dinosaurs'

- Spinosaurus: The Largest Carnivorous Dinosaur

- Stegosaurus: Bony Plates & Tiny Brain

- Triceratops: Facts about the Three-horned Dinosaur

- Tyrannosaurus Rex: Facts about T. Rex, King of the Dinosaurs

- Velociraptor: Facts about the 'Speedy Thief'

Time periods

Precambrian: Facts About the Beginning of Time

Paleozoic Era: Facts & Information

- Cambrian Period: Facts & Information

- Silurian Period Facts: Climate, Animals & Plants

- Devonian Period: Climate, Animals & Plants

- Permian Period: Climate, Animals & Plants

Mesozoic Era: Age of the Dinosaurs

- Triassic Period Facts: Climate, Animals & Plants

- Jurassic Period Facts

- Cretaceous Period: Facts About Animals, Plants & Climate

Cenozoic Era: Facts About Climate, Animals & Plants

Additional resources

- Apatosaurus louisae was the first specimen found at Dinosaur National Monument.

- The Yale Peabody Museum of Natural History features the mounted skeleton that O.C. Marsh used to describe the genus Brontosaurus.

- A mounted Apatosaurus skeleton is the focal point of the American Museum of Natural History's collection.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus