Pesticides Could Stunt Growth of Clams and Oysters

Negative effects from one of the most widely used herbicides in the United States could cascade through the aquatic food chain and even reach seafood eaters, new research finds.

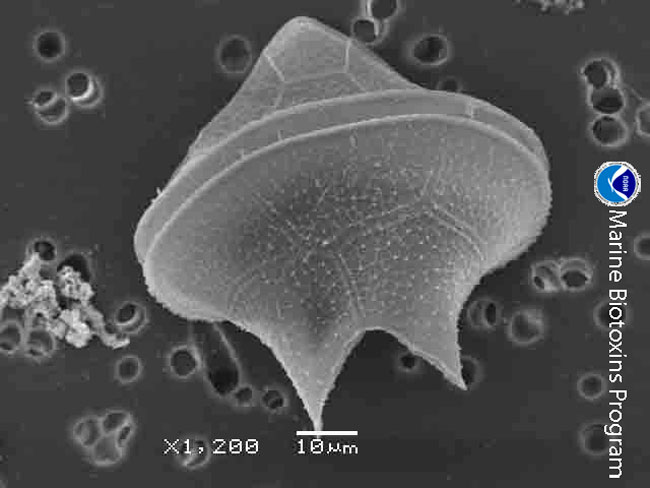

A group of researchers from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) found that exposure to the herbicide atrazine causes a significant decrease in the sizes of five species of algae--favorite foods for clams and oysters.

Farmers and landscape professionals rely on atrazine to inhibit growth and keep weedy grasses from taking over. The chemical blocks parts of photosynthesis, the process by which green plants use the sun's energy to turn water and carbon dioxide into nutrients for growth.

When atrazine runs off land and into rivers and estuaries, it can also block the food-making process in free-floating algae called phytoplankton. In the new study, the science team exposed algae to atrazine concentrations typical in estuarine environments. In most of the species tested, the amount of light energy transformed into protein growth plummeted.

Food empty of protein could lead to hungry and atrophied clams and oysters.

"Many aquatic animals such as clams and oysters rely on phytoplankton as a food source," said study team member Marie DeLorenzo, a NOAA research ecologist. "Disruption to the cellular composition of phytoplankton species may negatively affect nutritional levels of the plant, resulting in decreased growth rates for those animals that consume phytoplankton."

The scientists stress the importance of understanding the potential effects of a weed killer on non-target aquatic plants.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The research is published in the January issue of the journal Pesticide-Biochemistry and Physiology.?

- Top Ten Unexplained Phenomena

- Images: Endangered and Threatened Wildlife

- Marine Mammals Suffer Human Diseases

- New Data Show Global Warming Kills Marine Life

- Images: Under the Sea: Life in the Sanctuaries

Jeanna Bryner is managing editor of Scientific American. Previously she was editor in chief of Live Science and, prior to that, an editor at Scholastic's Science World magazine. Bryner has an English degree from Salisbury University, a master's degree in biogeochemistry and environmental sciences from the University of Maryland and a graduate science journalism degree from New York University. She has worked as a biologist in Florida, where she monitored wetlands and did field surveys for endangered species, including the gorgeous Florida Scrub Jay. She also received an ocean sciences journalism fellowship from the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. She is a firm believer that science is for everyone and that just about everything can be viewed through the lens of science.