6 weird animals that evolution came up with

These creatures have evolved unique appearances, impressive superpowers, and some strange habits.

1. Invisible frog

Most creatures hide their internal organs underneath multiple protective layers of skin, tissue and bone. But what if these layers were see-through?

Looking at a glass frog from above, you may not notice anything out of the ordinary. But if you were to flip it over, you would spy a tiny, fast-beating heart, a long, red vein, and a section of squirming intestines breaking down food. These amphibians have evolved to have extremely thin, translucent skin.

So why did these frogs evolve to be see-through? While these frogs' thin skin puts their entire internal anatomy on full display, when light shines on the frogs from above their silhouette becomes muddled to predators, according to a study published June 9 in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

These frogs live in the rainforests of Central and South America and spend much of their time perched on leaves. Because the frogs are surrounded by lush greenery, their vibrant-green topcoats are ideal for camouflage. Meanwhile, their more transparent legs blur the outlines of their bodies, making it tough for predators to recognize the frogs' shape, the study found.

Related: How many organs are in the human body?

2. Wasp-fig relationship

Unlikely relationships are often formed in the wild. For instance, fig wasps have found an unusual home inside figs. The fig "fruit" is actually a bundle of tiny flowers, called an inflorescence, which relies on fig wasps for pollination. In turn, the fleshy inflorescence provides a comfy and safe home for the wasps during their very short lives.

When female fig wasps hatch into the world, they are primed to "sniff out" receptive fig trees, or those whose flowers are ready for pollination, according to The Netherlands Entomological Society. Instinctively, the wasps search out the particular aroma emitted by female fig flowers, according to the U.S. Forest Service. Once they find a fig-in-need, the wasps dig their way into the soft, sweet flower through an opening at the end of the fig "fruit." The hole is so small that many wasps lose their wings and parts of their antennas. Once inside the fig, the female wasps are protected and out of sight, and they are able to lay their eggs. According to the Journal of Nematology, the wasps will not see the outside world ever again. The females die just 24 hours after laying their eggs.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

When the fig wasps hatch, the male hatchlings mate with the females, before digging escape routes out of the fig for the females. The male wasps spend their entire lives in the fig and die shortly after producing the tunnels.

This odd behavior has kept this wasp species alive for over 60 million years, according to an article published in 2005 in the journal Proceedings of the Royal Society B. Figs have these insects to thank for their continued existence, as their movement from one fig to another spreads their pollen.

3. Walking fish

Mexican walking fish (Ambystoma mexicanum), also called axolotls, are quirky creatures: Not only do these "fish" sport a protruding, spiky hairdo, they can also "walk." When they approach the bottom of a lake or canal, they pull out four legs from their sides to crawl around their swampy habitat in Mexico City.

Although they look like overdeveloped fish, they are actually amphibians. Often amphibians begin their lives equipped with gills so they can breathe underwater until they mature and lose their gills, ready for life on land. But axolotls keep their juvenile gills and remain in the water — a phenomenon called neoteny, according to an article in the journal Nature.

Never leaving the water, axolotls are found in the lakes of Xochimilco near Mexico City. Growing up to 12 inches (30 centimeters) long, they feed on small insects, worms, mollusks and crustaceans. Historically, these grinning creatures were at the top of the food chain, but invasive fish species — such as tilapia and carp fish, which eat baby axolotls — and pollution are now threatening their survival.

4. Pregnant males

Females don't always have to bear the brunt of pregnancy. According to Scientific American, for seahorses, pipefish and sea dragons — members of the Syngnathidae fish family — it's the males that get pregnant. Seahorses and pipefish carry their young inside brood pouches, supplying nutrients such as energy-rich fats through the pouch tissue, while sea dragons' eggs simply stick to the outside of the males’ tail.

This article is brought to you by How It Works.

How It Works is the action-packed magazine that's bursting with exciting information about the latest advances in science and technology, featuring everything you need to know about how the world around you — and the universe — works.

Is there any benefit to this arrangement? Because the females can focus solely on egg-making (leaving other baby-rearing roles to the males), seahorses can give birth in the morning and be pregnant again by the evening, according to National Geographic. This helps the species' numbers increase for a higher chance of survival.

With the males carrying the babies, the females are also less likely to be drained of energy. Usually, the females expend more energy producing eggs than the males do producing sperm, according to Oxford Academic. By transferring egg-carrying duties to males, the energy demand is shared more evenly.

5. Parasitic mates

Male and female anglerfish are so varied in appearance that you might think they were different species at first glance. The females are up to 60 times longer and half a million times heavier than their male partners; as such, when scientists first observed the males with the female anglerfish, they thought that they were looking at a mom and her young, according to an article published in a journal of the American Society of Ichthyologists and Herpetologists.

The most common images of anglerfish show the females. Found lurking mostly in the darkest depths of the Atlantic and Antarctic oceans, female anglerfish look like the stuff of nightmares: Light rods hang from their faces and terrifyingly large fangs protrude from their mouths.

But the arrival of the males makes everything even more peculiar. When mating, a male anglerfish acts like a parasite, according to New Scientist. Biting into the side of his chosen female, the tiny male fuses his body with hers so he can steal her nutrients by sucking out her blood. Since the male has no need to swim or see, his eyes, fins and some major organs begin to deteriorate. He gets everything he requires for little effort, while his only responsibilities are to provide reproductive cells when the time is right. At that time, the male and female release their sperm and eggs, respectively, into the water for fertilization, Live Science previously reported.

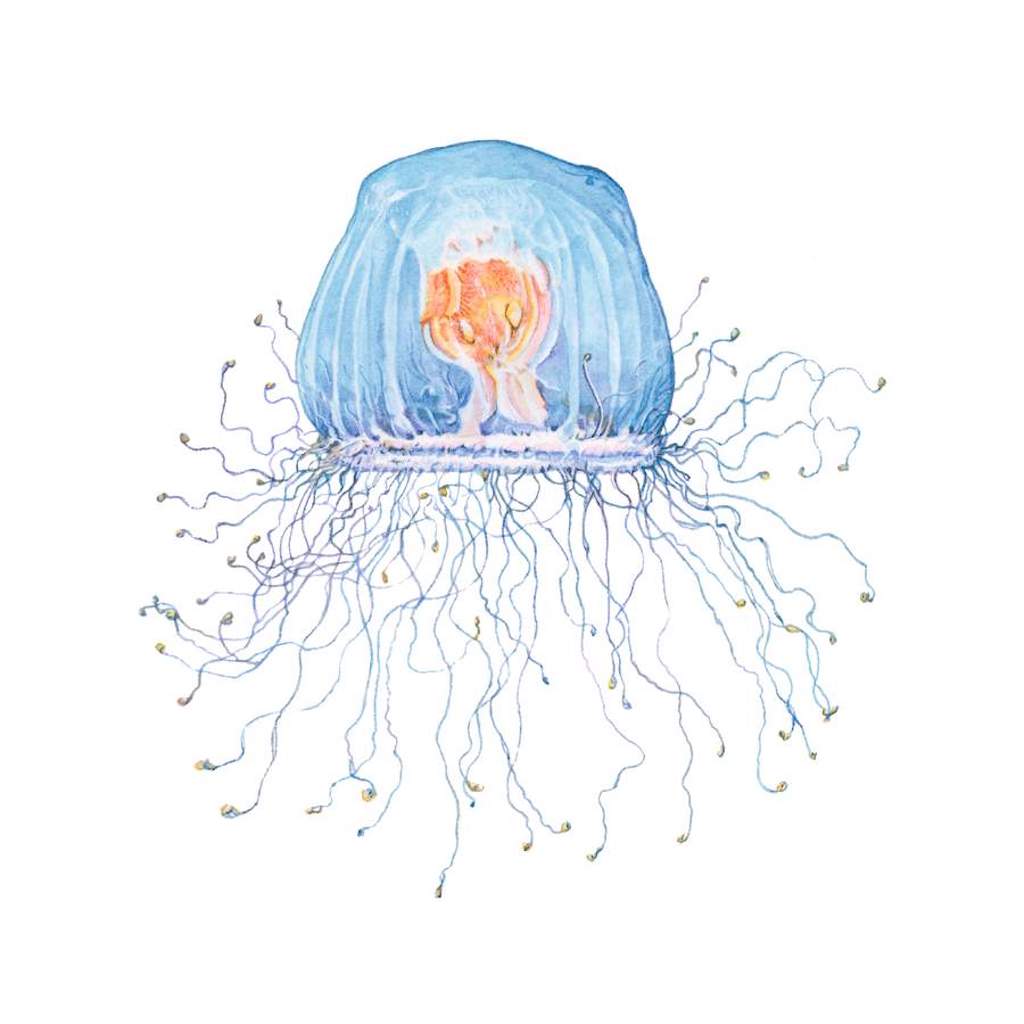

6. Immortal jellies

Do you ever wish you could jump back in time to when you were young and start life again? As time passes, our bodies are designed to grow, age and eventually die. However, not all species follow this cycle. Meet the immortal jellyfish, Turritopsis dohrnii.

When injured or in the face of starvation, this jellyfish can push the "reset" button, according to the American Museum of Natural History (AMNH). With that reset, the jellyfish adults reverts back to an earlier developmental stage, in this case a polyp. That new polyp then continues the life cycle and spawns lots of genetically identical medusas, or the tentacled creatures we call jellyfish. Scientists think the immortal jellyfish use a process called transdifferentiation to pull off this rejuvenating feat. In this process, an adult cell that has become specialized for a certain tissue can transform into a different kind of specialized cell, AMNH said.

At their largest, adults of this jellyfish are still less than 0.2 inches (5 millimeters) across. These jellyfish were first discovered in 1883 in the Mediterranean Sea, but they only gained the moniker of the immortal jellyfish in the mid-1990s. While a German student was studying them in a lab, he noticed the bizarre phenomenon. When the medusa stage of the jellyfish got stressed, it fell to the bottom of the holding jar and reverted straight into polyps, skipping any fertilization or larval stages, according to The Biologist, published by the Royal Society of Biology. The researchers liked it to "a butterfly transforming back into a caterpillar."

Next, researchers hope to figure out how the jellyfish accomplishes its everlasting life. "The genome of Turritopsis dohrnii is being investigated and decoding it will be the first step towards the search for an 'immortality switch,'" according to The Biologist.

The continuous cycle

Explore how these jellyfish reverse maturity to relive the cycle. Click the numbers below to learn more.

Ailsa is a staff writer for How It Works magazine, where she writes science, technology, history, space and environment features. Based in the U.K., she graduated from the University of Stirling with a BA (Hons) journalism degree. Previously, Ailsa has written for Cardiff Times magazine, Psychology Now and numerous science bookazines. Ailsa's interest in the environment also lies outside of writing, as she has worked alongside Operation Wallacea conducting rainforest and ocean conservation research.