Bowerbirds create stages that make them look bigger to potential partners. Fish and butterflies can flash what looks like a large, staring eye to intimidate predators or deflect attacks. Male peacock spiders raise their legs as part of a courtship ritual to make them seem much larger than they actually are.

These are just some of the strategies that help these animals survive and reproduce. They raise a fascinating question: Are animals fooled by optical illusions?

Researchers are finding that many of them do experience these perceptual quirks, though not always in the same way. "Illusions show that animals, as well as humans, can misinterpret visual information," Jennifer Kelley, an evolutionary biologist at the University of Western Australia, told Live Science in an email. "Information processing is expensive and costly, and since there is a limit on how much information can be obtained, brains take shortcuts."

Optical illusions are an important scientific tool because they reveal these shortcuts that brains use to turn raw sensory input into perceptions of reality. When something unexpected happens, scientists gain deeper insight into the rules that govern perception. If nonhuman animals are the subjects of these illusions, scientists can start to better understand how evolution has crafted similar rules to improve survival and aid reproduction.

Sign up for our weekly Life's Little Mysteries newsletter to get the latest mysteries before they appear online.

"Many animals use visual strategies such as size exaggeration or camouflage because perception is not about reproducing reality faithfully, but about survival," Maria Santacà, a researcher into animal behavior and cognition at the University of Vienna, told Live Science in an email.

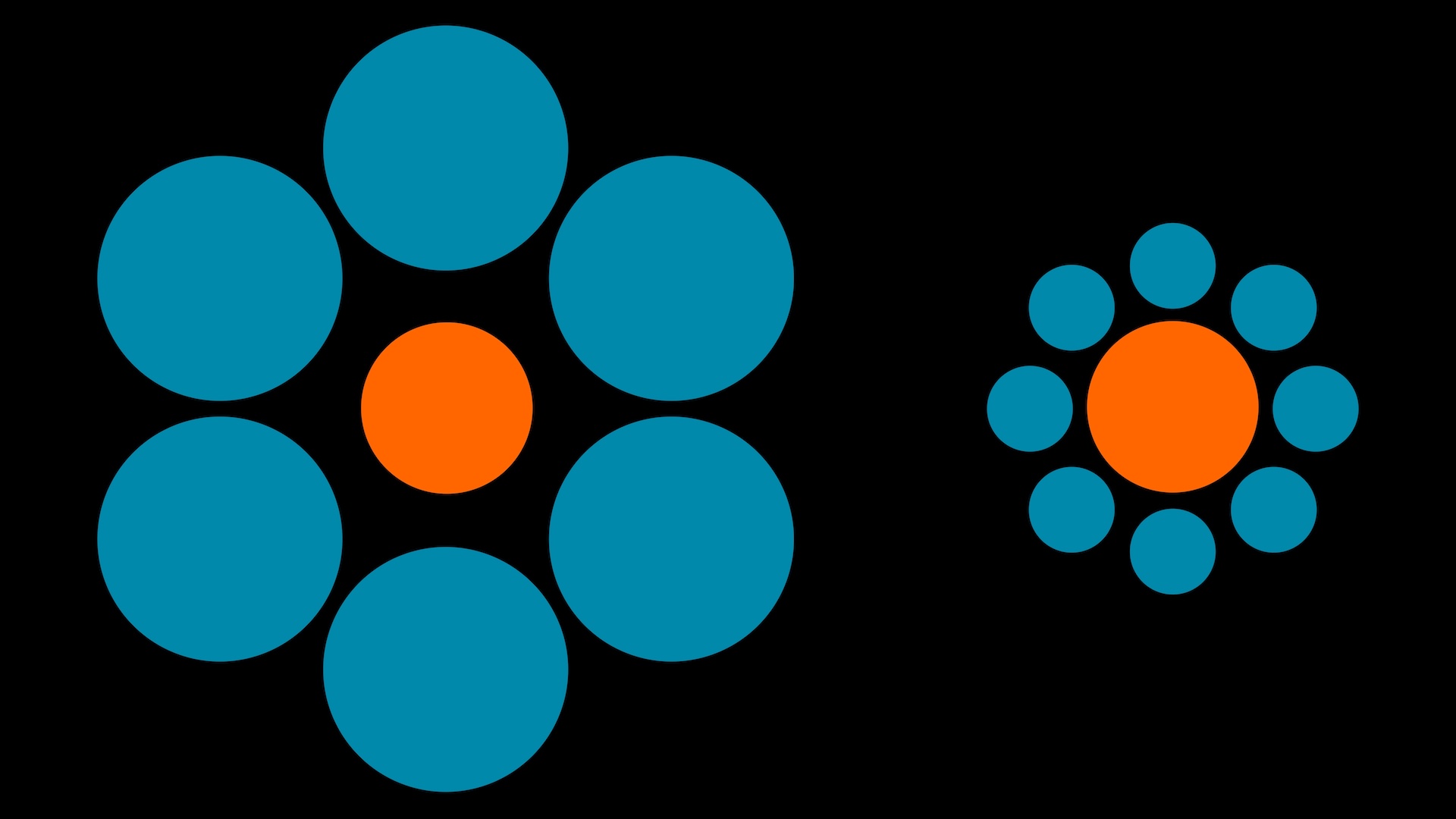

Size illusions are perhaps the best-known visual tricks. Humans fall for them all the time. A classic of the genre is the Ebbinghaus illusion, which shows how one circle surrounded by smaller circles looks a lot larger than the same circle surrounded by bigger circles.

Guppies fall for this illusion, too. Santacà was lead author on a 2025 study, which demonstrated that when a circle of food flakes was surrounded by smaller disks, the fish chose them more often, as if there were genuinely more food in the circle. Contrastingly, ring doves, when tested with the same setup using millet seeds, didn't consistently fall for the illusion.

The likely explanation lies in the two species' respective ecosystems, Santacà said. "Guppies live in dynamic underwater habitats with variable light and complex backgrounds, so their visual system emphasizes global processing, integrating the whole scene. Doves, by contrast, feed on small seeds against textured ground surfaces, which requires precise local discrimination. Their perception could therefore be optimized for detail rather than context, making them less prone to this particular illusion."

Context matters

It turns out that who an animal hangs around with can amplify these illusions. Female fiddler crabs prefer males with large claws, but attractiveness is relative. A male flanked by two smaller-clawed rivals is more attractive to a female than the same male surrounded by bigger neighbors. This context effect mirrors the Ebbinghaus illusion and suggests that males can boost their perceived appeal simply by courting near less-imposing neighbors.

"These strategies exploit the way visual systems interpret context, helping animals appear larger to rivals, smaller to predators." Santancà argued. "In nature, what matters is not to be seen accurately, but to be perceived in the most advantageous way."

Not all species follow the same script: Pigeons are subject to the Ebbinghaus effect, but in reverse, while baboons are completely unaffected by the illusion. Kelley argued that "this suggests that brains are wired differently across species, which is not surprising due to variations in physiology and because the information that is most relevant may differ among species."

Not only do animals perceive illusions, but some are masters of creating these tricks. "Males may not only use features of their body to appear large (and therefore more attractive) but may utilise and/or modify their physical or social environment to alter the female’s perception of size," Kelley said.

Male great bowerbirds, for instance, arrange pebbles from small to large along the floor of their bower (an area they build to impress females as part of a courtship ritual) to create a forced perspective illusion, a 2010 study found. Objects that are farther away should take up less room in the field of vision than closer objects of the same size do. From the female's perspective, the fact that this isn't true makes the bower look shorter and thus the male appear larger.

Others are tricked by illusions about their own bodies. Octopuses can be fooled by a version of the "rubber hand illusion," a trick long thought to be unique to humans. In experiments, researchers stroked a real octopus arm hidden from view and a visible fake octopus arm at the same time. When the fake arm was pinched, the octopus reacted as if its own arm had been attacked — changing color or pulling back. A similar experiment found that mice were also duped by this illusion. The fact that octopus and rodent nervous systems evolved completely separately from ours makes it all the more surprising that they should also be subject to the illusion.

Camouflage as illusion

Camouflage offers another example. Disruptive coloration uses high-contrast patches toward the edges of prey bodies to create false boundaries that confuse predators' edge-detection systems. Countershading — which is common in fish, reptiles and mammals — grades color from dark on top to light below. Because the sun comes from above, light bellies are thought to make prey harder to spot from below. Similarly, a 2013 study found that dark prey backs are thought to blend in better with darker ground or the depths of the ocean, which confuses predators that are hunting from above.

"Countershading is probably so widespread because it solves a very fundamental problem — how to avoid being detected by predators when directional light produces regions of brightness/darkness across the body," Kelley said.

In the same way the surroundings can distort size in the Ebbinghaus illusion, context also warps brightness and color. A gray patch looks darker against a pale background — a phenomenon called simultaneous brightness contrast. Similar effects occur for color. Insects, fish and birds all show these biases, which suggests a common mechanism for processing contrasting colors and shades. The illusion might be useful to courting males to help make themselves look brighter or for animals that change color to stand out from the background.

Illusions demonstrate that perception is not about perfect accuracy; it is about what works in a given environment. As Kelley told Live Science: "It’s always ultimately about survival and reproduction!"

For guppies, integrating context may help gauge rivals or mates in a flickering stream. For doves, precision trumps context when pecking seeds. When animals themselves deploy illusions, they exploit these neural shortcuts as survival strategies. The gap between reality and perception is a rich space for evolution to do some of its most creative work.

Kit Yates is a professor of mathematical biology and public engagement at the University of Bath in the U.K. He reports on mathematics and health stories, and was an Association of British Science Writers media fellow at Live Science during the summer of 2025.

His science journalism has won awards from the Royal Statistical Society and The Conversation, and has written two popular science books, The Math(s) of Life and Death and How to Expect the Unexpected.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus