Can brainless animals think?

Even without brains, creatures like jellyfish and sea anemones can learn from experience.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

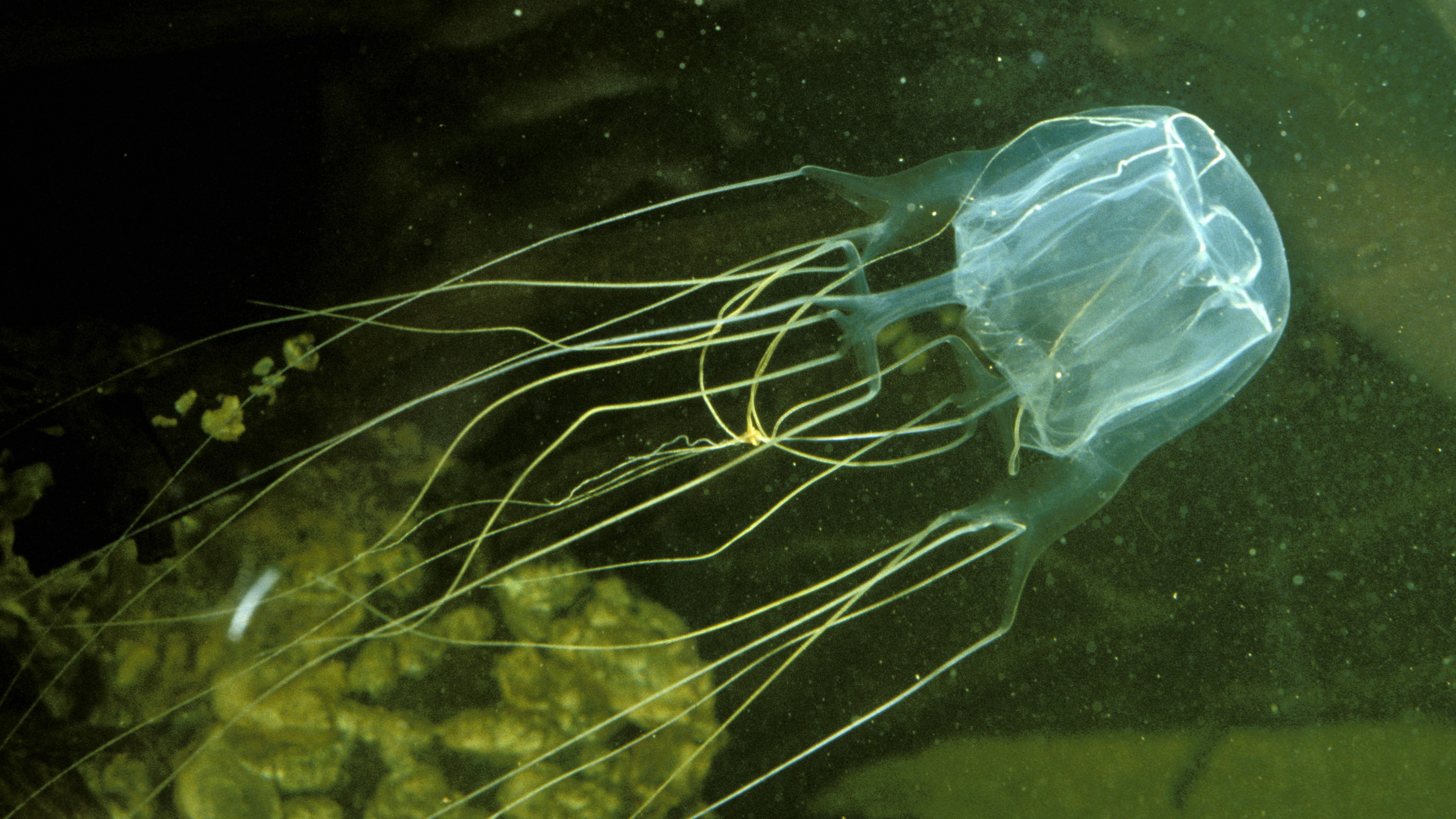

Creatures like sea stars, jellyfish, sea urchins and sea anemones don't have brains, yet they can capture prey, sense danger and react to their surroundings.

So does that mean brainless animals can think?

"Brainless does not necessarily mean neuron-less," Simon Sprecher, a professor of neurobiology at the University of Fribourg in Switzerland, told Live Science in an email. Apart from marine sponges and the blob-like placozoans, all animals have neurons, he said.

Creatures like jellyfish, sea anemones and hydras possess diffuse nerve nets — webs of interconnected neurons distributed throughout the body and tentacles, said Tamar Lotan, head of the Cnidarian Developmental Biology and Molecular Ecology Lab at the University of Haifa in Israel.

"The nerve net can process sensory input and generate organized motor responses (e.g., swimming, contraction, feeding, and stinging), effectively performing information integration without a brain," she told Live Science in an email.

Sign up for our weekly Life's Little Mysteries newsletter to get the latest mysteries before they appear online.

This simple setup can support surprisingly advanced behavior. Sprecher's team showed that the starlet sea anemone (Nematostella vectensis) can form associative memories — learning to link two unrelated stimuli. In the experiment, the researchers trained sea anemones to associate a harmless flash of light with a mild shock. Eventually, the light alone made them retract.

Another experiment showed that sea anemones can learn to recognize genetically identical neighbors after repeated encounters and curb their usual territorial aggression. The fact that anemones change their behavior toward genetically identical neighbors suggests they can distinguish between "self" and "non-self".

A study led by Jan Bielecki, a neurobiologist at Kiel University in Germany, showed that box jellyfish can associate visual cues with the physical sensation of bumping into objects, helping them navigate around obstacles more effectively.

"It is my core belief that learning can be achieved by single neurons," Bielecki told Live Science in an email.

So if animals with nerve nets instead of brains can remember and learn from experience, does that mean they can think?

"This is a tricky question to answer," Sprecher said. The definition of 'thinking' depends on the field. Psychologists, biologists and neuroscientists define 'thinking' differently, Bielecki noted.

Additionally, "thinking is too vague a concept," Bielecki said. Scientists study things like decision-making, pattern recognition, associative learning, memory formation and inductive reasoning. Each has their own, much narrower definition.

Ken Cheng, a professor of animal behavior at Macquarie University in Australia, noted that scientists tend to use the word "cognition" instead of "thinking."

"Scientists shy away from the term 'thinking' because thinking, to most of us, means something running through the head, and we don't have a good way to verify that in another animal or nonanimal species," Cheng told Live Science. Even "cognition" does not have an agreed-upon definition, he said, but "in the broadest sense, cognition is information processing — using information from the world, including the world inside an organism, to do things."

If thinking is that broad sense of cognition, then all life-forms think, Cheng said. This includes animals like marine sponges and placozoans, which process information about their surroundings to keep themselves alive. But when it comes to "advanced cognition," which goes beyond basic learning, however, scientists aren't sure whether brainless animals can think, Cheng said.

Basic cognition can be regarded as any change in behavior that goes beyond reflexes, Sprecher said. By that definition, brainless animals do show cognition. "However, more advanced types of cognitive abilities might require consciousness or self-awareness," he said.

Lotan pointed out that cnidarians (an animal family that includes jellyfish, sea anemones and many other marine invertebrates), which evolved more than 700 million years ago, continue to thrive while many animals with brains have long disappeared.

"This resilience suggests that they possess a unique adaptive system enabling them to endure and flourish through extreme environmental changes over geological timescales — despite lacking a brain," she said. Their neurons allow them to sense and interpret their surroundings, "perhaps representing a rudimentary form of thinking."

Brain quiz: Test your knowledge of the most complex organ in the body

Clarissa Brincat is a freelance writer specializing in health and medical research. After completing an MSc in chemistry, she realized she would rather write about science than do it. She learned how to edit scientific papers in a stint as a chemistry copyeditor, before moving on to a medical writer role at a healthcare company. Writing for doctors and experts has its rewards, but Clarissa wanted to communicate with a wider audience, which naturally led her to freelance health and science writing. Her work has also appeared in Medscape, HealthCentral and Medical News Today.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus