New Sea Dragon Species Flaunts Ruby-Red Skin

For the first time in 150 years, researchers have found a new species of sea dragon, a marine creature with "unusual red coloration," according to a new study.

Scientists discovered the new species, Phyllopteryx dewysea, while they were studying ways to protect the two known species of sea dragons — the orange-tinted leafy sea dragon and the yellow-and-purple common sea dragon — both of which are native to Australian waters. During their work at the Western Australian Museum, they came across a pregnant male sea dragon, carrying dozens of babies, with ruby-red coloring. The sea dragon had been caught in 2007, off the remote Recherche Archipelago near Australia's southern coast.

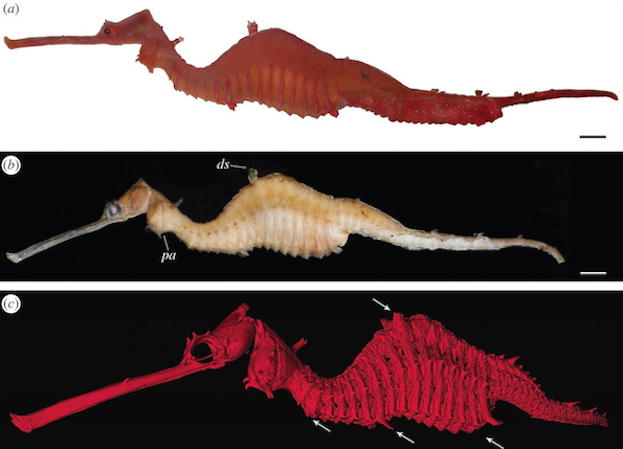

With its vibrant body color, pink vertical bars on each of its 18 trunk segments and light markings on its snout, the flashy 9.4-inch-long (24 centimeters) sea dragon looked different from the two known species, the researchers said. (Sea dragons are marine creatures related to sea horses, but they have a longer snout and a longer tail that doesn't curl.) [Top 10 Beasts and Dragons: How Reality Made Myth]

A more thorough visual inspection and a genetic analysis explained why they looked different: The ruby-red sea dragon was an entirely distinct species, the researchers found. Moreover, a genetic analysis showed that P. dewysea's mitochondrial DNA (the DNA passed down by mothers) was 7.4 percent different from that of the common sea dragon (Phyllopteryx taeniolatus) and 13.1 percent different from that of the leafy sea dragon (Phycodurus eques).

"We're now in a golden age of taxonomy, and these powerful DNA tools are making it possible for more new species than ever to be discovered," Greg Rouse, one of the study's researchers and a professor of marine biology at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography at the University of California, San Diego, said in a statement. "This latest finding provides further proof of the value of scientific collections and museum holdings."

The researchers also used computer tomography (CT) to scan the new sea dragon with 5,000 X-ray slices. Using the slices, they created a rotating 3D model of P. dewysea.

Unlike its sea dragon relatives, P. dewysea lives in deep waters off the southern coast of Australia. The deepest record for the common sea dragon is 108 feet (33 meters), but researchers found the new sea dragon at depths of 236 feet (72 m). Its unusually deep habitat may explain why scientists haven't noticed it until now, the researchers said."We could then see several features of the skeleton that were distinct from the other two species, corroborating the genetic evidence, said Scripps graduate student Josefin Stiller.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

What's more, the sea dragon's red coloring could serve as camouflage in the ocean's deep, dark waters, they said.

Since the new species was identified, Nerida Wilson, a marine biologist at the Western Australian Museum, looked for more ruby sea dragon specimens. She found one that had washed ashore at Perth in 1919, and located two others in the Australian National Fish Collection.

"It has been 150 years since the last sea dragon was described, and all this time, we thought that there were only two species," Wilson said. "Suddenly, there is a third species! If we can overlook such a charismatic new species for so long, we definitely have many more exciting discoveries awaiting us in the oceans."

The study was published today (Feb. 18) in the journal Royal Society Open Science.

Follow Laura Geggel on Twitter @LauraGeggel. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Laura is the managing editor at Live Science. She also runs the archaeology section and the Life's Little Mysteries series. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.