Science news this week: 'Anti-aging' magic mushrooms and record-breaking internet speeds

July 19, 2025: Our weekly roundup of the latest science in the news, as well as a few fascinating articles to keep you entertained over the weekend.

Kicking off with the most massive black hole merger ever detected, it's been a pretty explosive week for science news.

On Earth, a giant, lava-spewing fissure opened up along Iceland's Sundhnúkur crater row on Wednesday (July 16) following an earthquake swarm in the region. The eruption spread to a second fissure, with the larger fissure measuring around 1.5 miles (2.4 kilometers) long and the smaller one coming in at about 1,600 feet (500 m).

This week, geologists have also revealed that large-scale volcanic eruptions on Earth's surface may be driven by enormous underground "BLOBS".

Elsewhere in our solar system, the sun has had a particularly active week, sending out a series of giant plasma plumes, including one dubbed "The Beast." The projection of plasma stretched more than 100,000 miles (165,000 km) across — that’s 13 times the width of our planet.

Fastest internet record

Japan sets new internet speed record — it's 4 million times faster than average US broadband speeds

Researchers in Japan have set a new world record for the fastest internet speed using a new form of optical fibers, capable of transmitting over 125,000 gigabytes of data per second over 1,120 miles (1,802 km). That's about 4 million times the average broadband speed in the U.S. and more than twice the previous world record set in 2024.

Data traffic volumes worldwide are expected to grow significantly in the coming years, and new high-capacity optical communication systems like this will be required to meet the increased demand.

Discover more technology news

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

—Penny-sized laser could help driverless cars see the world so much clearer

Life's little mysteries

What's Earth's lowest point on land?

When we talk about mountains and other tall geological structures, we usually compare their height against sea level. For example, Mount Everest, the tallest mountain on Earth, towers more than 29,000 feet (8,800 m) above sea level. But can land ever go below sea level? And what is the lowest point on land?

—If you enjoyed this, sign up for our Life's Little Mysteries newsletter

Anti-aging magic mushrooms

'I was floored by the data': Psilocybin shows anti-aging properties in early study

Psilocybin is the main psychoactive ingredient in magic mushrooms. It may also, in small quantities, have a range of therapeutic potentials, with studies showing promising results in treating anxiety, depression and neurodegenerative disorders like Alzheimer's disease. Now, scientists have found that psilocybin may also delay cellular aging.

By looking at isolated human cells in a lab, scientists found that the drug extended the cells' lifespan by up to 57%, depending on the dosage given. Meanwhile, the drug was shown to increase the lifespan of aging mice and improve their fur quality, in a transformation that the researchers described as "dramatic."

"I was floored by the data," Louise Hecker, study senior author and an associate professor at Baylor College of Medicine in Houston, told Live Science.

Discover more health news

—Scientists grow mini amniotic sacs in the lab using stem cells

—A single MRI can reveal how quickly you're aging, scientists claim

Also in science news this week

—The 'gender gap' in math is not innate — something about school drives it

—Watch first-of-its-kind robot elephant go bowling

—Scientists discover long-lost giant rivers that flowed across Antarctica up to 80 million years ago

Science spotlight

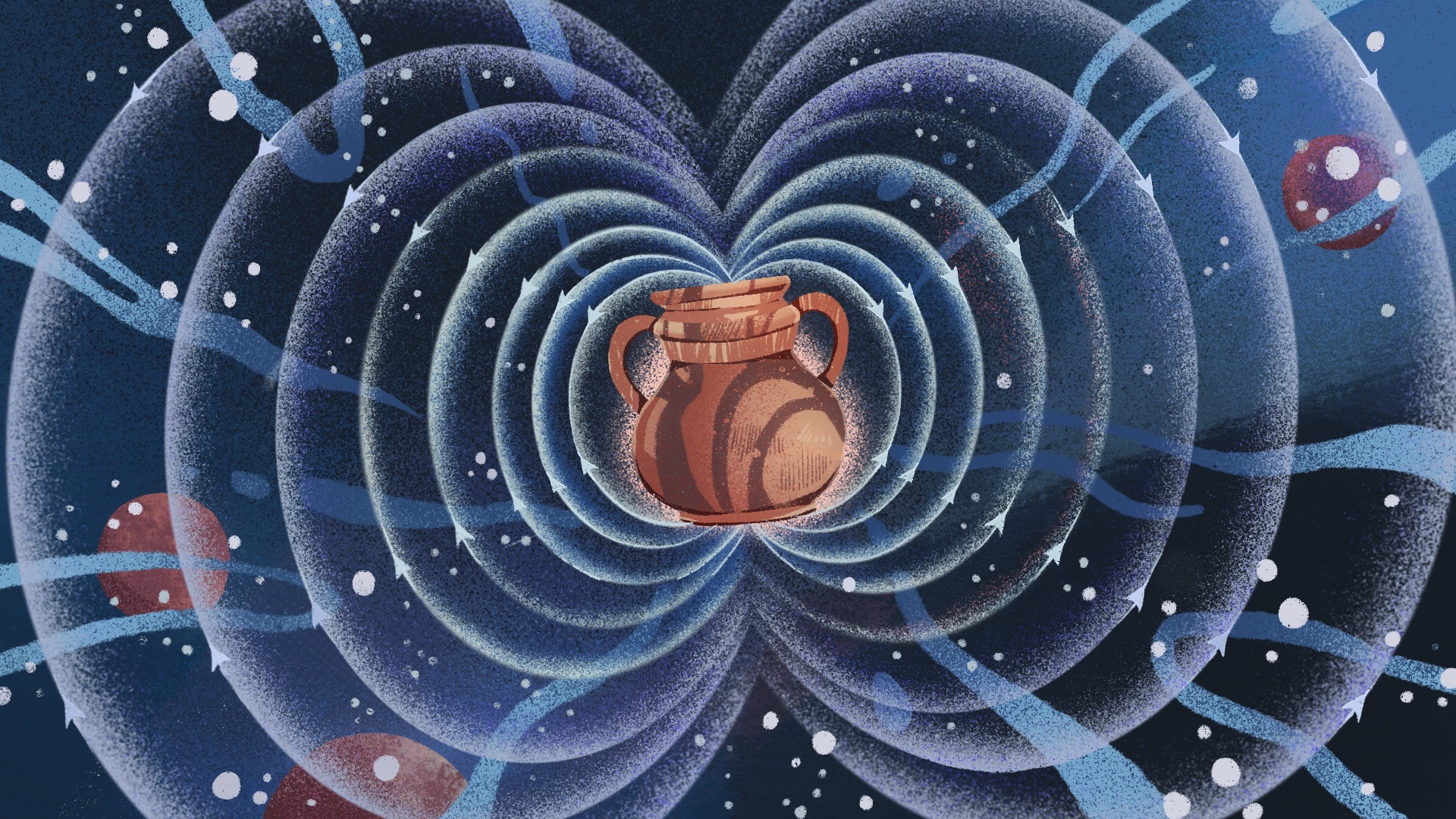

Earth's magnetic field is weakening — magnetic crystals from lost civilizations could hold the key to understanding why

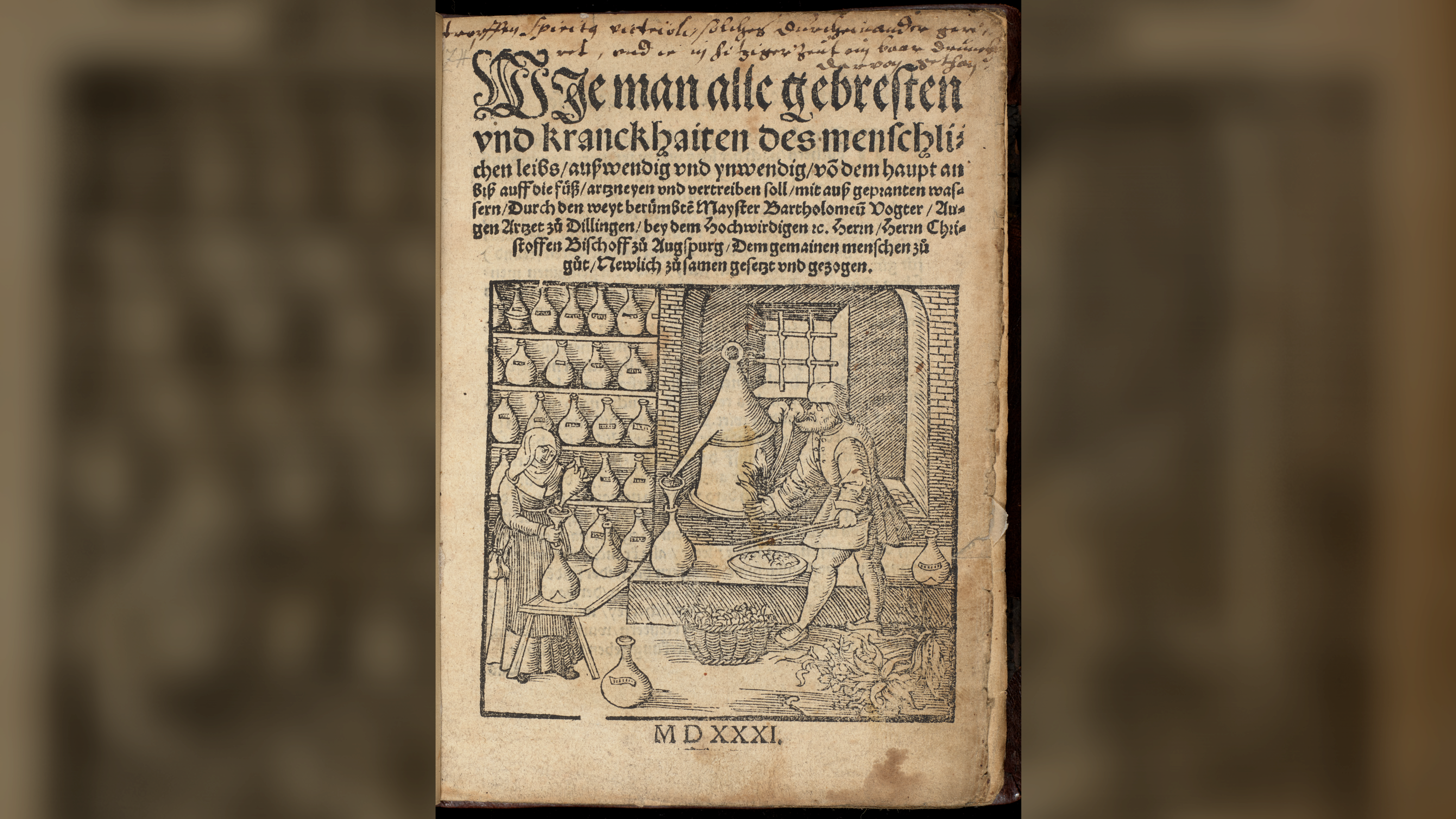

In 2008, archaeologist Erez Ben-Yosef from Tel Aviv University accidentally discovered the strongest magnetic field anomaly ever found after unearthing a piece of Iron Age "trash." On examination, the hunk of copper slag — a waste byproduct of forging metals — recorded an intense spike in Earth's magnetic field around 3,000 years ago; so intense that existing geological models were not able to explain it.

After collecting more archaeological samples from around the area in southern Jordan, Ben-Yosef and geologist Ron Shaar from the Hebrew University of Jerusalem were able to confirm intense surges in the Earth's magnetic field, emanating from the Middle East, from around 1100 to 550 B.C.

So what do these findings tell us about Earth's mysterious magnetic field, and how can it be used to make predictions about the field in the future?

Something for the weekend

If you're looking for something a little longer to read over the weekend, here are some of the best long reads, book excerpts and interviews published this week.

—Why giant moa — a bird that once towered over humans — are even harder to de-extinct than dire wolves [Analysis]

—The choice of sperm is 'entirely up to the egg' — so why does the myth of 'racing sperm' persist? [Book extract]

—Why is color blindness so much more common in men than in women? [Query]

And something for the skywatchers:

Science in motion

Do sloths fart? Cute new video finally settles age old question

For years, scientists had assumed that sloths don't fart — believing that the methane produced by their slow digestive system was simply absorbed into their bloodstreams and breathed out through their mouths. That was until researchers caught a baby sloth tooting on camera.

The video, shared by zoologist and presenter Lucy Cooke and wildlife veterinarian Andrés Sáenz Bräutigam on Instagram on Tuesday (July 15), shows a baby Hoffman's two-toed sloth (Choloepus hoffmanni) letting rip in a bucket of water.

"Yes, sloths do fart. And I may have just witnessed the first documented case," Cooke said.

Follow Live Science on social media

Want more science news? Follow our Live Science WhatsApp Channel for the latest discoveries as they happen. It's the best way to get our expert reporting on the go, but if you don't use WhatsApp, we're also on Facebook, X (formerly Twitter), Flipboard, Instagram, TikTok, Bluesky and LinkedIn.

Pandora is the trending news editor at Live Science. She is also a science presenter and previously worked as Senior Science and Health Reporter at Newsweek. Pandora holds a Biological Sciences degree from the University of Oxford, where she specialised in biochemistry and molecular biology.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus