Pluto Should Be a Planet and So Should Earth's Moon, New Study Claims

Sing along if you know the words: When the moon hits your eye, like a big pizza pie, that's a planet!

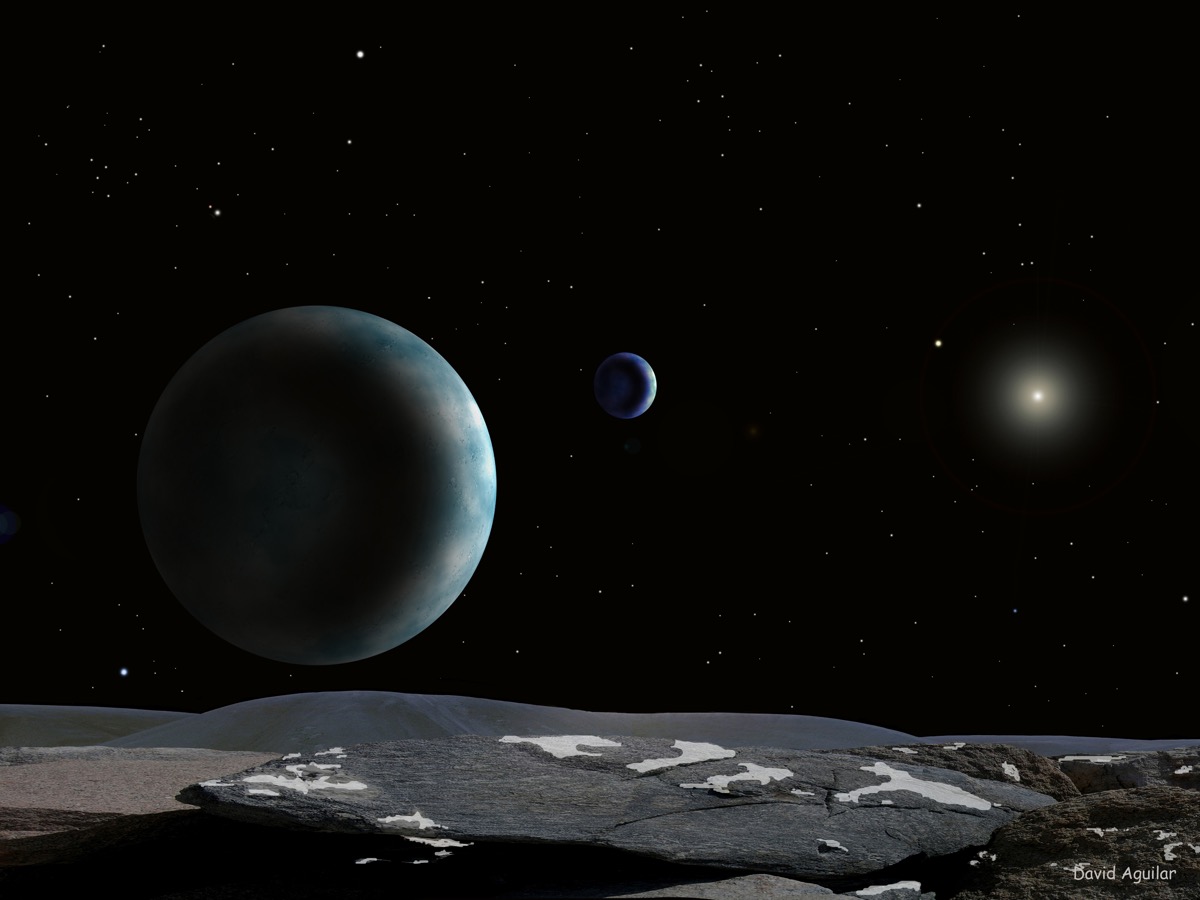

That's what ancient Greek stargazers thought, anyway. And according to a team of astronomers writing online Aug. 29 in the journal Icarus, maybe it's time we started thinking of Earth's trusty satellite — plus demoted dwarf planets like Pluto and Ceres — as a full-fledged planets once again.

That might sound odd, but it's well within the consensus established by centuries of scientific literature, the new study argues. The authors of that study scoured more than 200 years of scientific research to try to answer two simple questions: What makes a planet, according to the scientific community; and does that definition fall in line with the criteria that the International Astronomical Union (IAU) used in 2006 when they famously stripped Pluto of its planethood? [Top 10 Amazing Moon Facts]

The IAU's judgment on Pluto (and therefore all celestial bodies seeking planethood) does not speak for the scientific community, the authors determined.

"There are 120 examples I found of scientists in the recent published literature violating the IAU definition, calling something a planet even though the IAU definition says it's not a planet," lead study author Philip Metzger, a planetary scientist at the University of Central Florida, told NBCNews.com. "The reason planetary scientists do this is because the IAU definition is not useful for science."

What makes a planet?

After 76 years of textbook planet status, Pluto was demoted to a dwarf planet in 2006 when the IAU voted that the icy orb failed to meet a set of criteria established by decades of scientific literature.

To be a planet, they said, Pluto must: 1) Orbit the sun; 2) Be massive enough to it pull itself into a sphere shape under its own gravity; 3) "Clear its neighborhood" of debris and other celestial bodies, proving it has gravitational dominance in its corner of the solar system.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Pluto fails that third criterion. Because it orbits in the Kuiper Belt — a massive ring of asteroids and planetoids that stretches beyond the orbit of Neptune — Pluto is surrounded by thousands of other celestial bodies and hunks of debris, each exerting its own gravity. Pluto, then, is not the gravitationally dominant object in its neighborhood — and therefore, the IAU said, not a full-fledged planet.

According to Metzger and his colleagues, however, that third bit of the criterion is unnecessarily narrow — and not reflected in the consensus of past research. After looking at hundreds of published astronomy papers going back to the 1800s, the researchers found that, while most writers agreed that planets should be spherical and orbit the sun, the "clearing the neighborhood" rule appeared only in a single 1801 paper.

The researchers concluded that this Pluto-excluding rule is "arbitrary and not based on historical precedent," and should be therefore ignored when defining any present or future planet-size objects in our universe.

"When Galileo described the moons of Jupiter, he described them as planets," study co-author Kirby Runyon, a planetary geologist at the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory, told NBCNews.com. "So, the actual historical precedent is to consider round worlds that orbit other planets as planets, too. And we consider dwarf planets to be full-fledged planets."

By this revised standard Pluto is a planet. So is Earth's moon, and the moons of Jupiter and Saturn. That's a controversial view that has already garnered some astro-criticism — and the study authors are fine with that. If anyone disagrees with their assessment, the researchers wrote, it should be up to the consensus of scientific literature to change it, not a vote by a single authority like the IAU.

The study will be detailed in the February 2019 print issue of Icarus.

Originally published on Live Science.

Brandon is the space / physics editor at Live Science. With more than 20 years of editorial experience, his writing has appeared in The Washington Post, Reader's Digest, CBS.com, the Richard Dawkins Foundation website and other outlets. He holds a bachelor's degree in creative writing from the University of Arizona, with minors in journalism and media arts. His interests include black holes, asteroids and comets, and the search for extraterrestrial life.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus