What Is Electrical Engineering?

Electrical engineering is one of the newer branches of engineering, and dates back to the late 19th century. It is the branch of engineering that deals with the technology of electricity. Electrical engineers work on a wide range of components, devices and systems, from tiny microchips to huge power station generators.

Early experiments with electricity included primitive batteries and static charges. However, the actual design, construction and manufacturing of useful devices and systems began with the implementation of Michael Faraday's Law of Induction, which essentially states that the voltage in a circuit is proportional to the rate of change in the magnetic field through the circuit. This law applies to the basic principles of the electric generator, the electric motor and the transformer. The advent of the modern age is marked by the introduction of electricity to homes, businesses and industry, all of which were made possible by electrical engineers.

Some of the most prominent pioneers in electrical engineering include Thomas Edison (electric light bulb), George Westinghouse (alternating current), Nikola Tesla (induction motor), Guglielmo Marconi (radio) and Philo T. Farnsworth (television). These innovators turned ideas and concepts about electricity into practical devices and systems that ushered in the modern age.

Since its early beginnings, the field of electrical engineering has grown and branched out into a number of specialized categories, including power generation and transmission systems, motors, batteries and control systems. Electrical engineering also includes electronics, which has itself branched into an even greater number of subcategories, such as radio frequency (RF) systems, telecommunications, remote sensing, signal processing, digital circuits, instrumentation, audio, video and optoelectronics.

The field of electronics was born with the invention of the thermionic valve diode vacuum tube in 1904 by John Ambrose Fleming. The vacuum tube basically acts as a current amplifier by outputting a multiple of its input current. It was the foundation of all electronics, including radios, television and radar, until the mid-20th century. It was largely supplanted by the transistor, which was developed in 1947 at AT&T's Bell Laboratories by William Shockley, John Bardeen and Walter Brattain, for which they received the 1956 Nobel Prize in physics.

What does an electrical engineer do?

"Electrical engineers design, develop, test and supervise the manufacturing of electrical equipment, such as electric motors, radar and navigation systems, communications systems and power generation equipment, states the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. "Electronics engineers design and develop electronic equipment, such as broadcast and communications systems — from portable music players to global positioning systems (GPS)."

If it's a practical, real-world device that produces, conducts or uses electricity, in all likelihood, it was designed by an electrical engineer. Additionally, engineers may conduct or write the specifications for destructive or nondestructive testing of the performance, reliability and long-term durability of devices and components.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

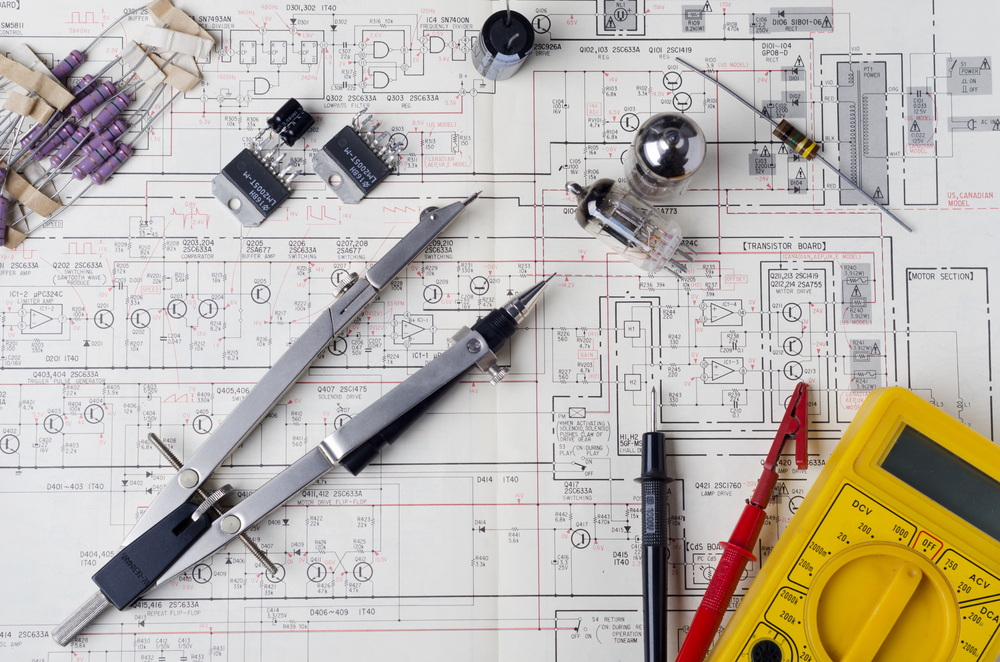

Today’s electrical engineers design electrical devices and systems using basic components such as conductors, coils, magnets, batteries, switches, resistors, capacitors, inductors, diodes and transistors. Nearly all electrical and electronic devices, from the generators at an electric power plant to the microprocessors in your phone, use these few basic components.

Critical skills needed in electrical engineering include an in-depth understanding of electrical and electronic theory, mathematics and materials. This knowledge allows engineers to design circuits to perform specific functions and meet requirements for safety, reliability and energy efficiency, and to predict how they will behave, before a hardware design is implemented. Sometimes, though, circuits are constructed on "breadboards," or prototype circuit boards made on computer numeric controlled (CNC) machines for testing before they are put into production.

Electrical engineers are increasingly relying on computer-aided design (CAD) systems to create schematics and lay out circuits. They also use computers to simulate how electrical devices and systems will function. Computer simulations can be used to model a national power grid or a microprocessor; therefore, proficiency with computers is essential for electrical engineers. In addition to speeding up the process of drafting schematics, printed circuit board (PCB) layouts and blueprints for electrical and electronic devices, CAD systems allow for quick and easy modifications of designs and rapid prototyping using CNC machines. A comprehensive list of necessary skills and abilities for electrical and electronics engineers can be found at MyMajors.com.

Electrical engineering jobs and salaries

Electrical and electronics engineers work primarily in research and development industries, engineering services firms, manufacturing and the federal government, according to the BLS. They generally work indoors, in offices, but they may have to visit sites to observe a problem or a piece of complex equipment, the BLS says.

Manufacturing industries that employ electrical engineers include automotive, marine, railroad, aerospace, defense, consumer electronics, commercial construction, lighting, computers and components, telecommunications and traffic control. Government institutions that employ electrical engineers include transportation departments, national laboratories and the military.

Most electrical engineering jobs require at least a bachelor's degree in engineering. Many employers, particularly those that offer engineering consulting services, also require state certification as a Professional Engineer. Additionally, many employers require certification from the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE) or the Institution of Engineering and Technology (IET). A master's degree is often required for promotion to management, and ongoing education and training are needed to keep up with advances in technology, testing equipment, computer hardware and software, and government regulations.

As of July 2014, the salary range for a newly graduated electrical engineer with a bachelor's degree is $55,570 to $73,908, according to Salary.com. The range for a mid-level engineer with a master's degree and five to 10 years of experience is $$74,007 to $108,640, and the range for a senior engineer with a master's or doctorate and more than 15 years of experience is $97,434 to $138,296. Many experienced engineers with advanced degrees are promoted to management positions or start their own businesses where they can earn even more.

The future of electrical engineering

Employment of electrical and electronics engineers is projected to grow by 4 percent between now and 2022, because of these professionals' "versatility in developing and applying emerging technologies," the BLS says.

The applications for these emerging technologies include studying red electrical flashes, called sprites, which hover above some thunderstorms. Victor Pasko, an electrical engineer at Penn State, and his colleagues have developed a model for how the strange lightning evolves and disappears.

Another electrical engineer, Andrea Alù, of the University of Texas at Austin, is studying sound waves and has developed a one-way sound machine. "I can listen to you, but you cannot detect me back; you cannot hear my presence," Alù told LiveScience in a 2014 article.

And Michel Maharbiz, an electrical engineer at the University of California, Berkeley, is exploring ways to communicate with the brain wirelessly.

The BLS states, "The rapid pace of technological innovation and development will likely drive demand for electrical and electronics engineers in research and development, an area in which engineering expertise will be needed to develop distribution systems related to new technologies."

Additional resources

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus