What 11 Billion People Mean for Food Security

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Editor's note: By the end of this century, Earth may be home to 11 billion people, the United Nations has estimated, earlier than previously expected. As part of a week-long series, LiveScience is exploring what reaching this population milestone might mean for our planet, from our ability to feed that many people to our impact on the other species that call Earth home to our efforts to land on other planets. Check back here each day for the next installment.

Beetles, scorpions and other insects may not be found on most restaurant menus — at least in the Western world — but they may need to find a place in human diets, if society is to feed the world's booming population.

At least that's one solution, albeit an unconventional one, offered up in a 200-page-plus report released in May by the United Nations' Food and Agriculture Organization, in which the group outlined the potential of edible insects to help alleviate food insecurity in the present and future.

"To meet the food and nutrition challenges of today — there are nearly 1 billion chronically hungry people worldwide — and tomorrow, what we eat and how we produce it needs to be re-evaluated," the report reads. "We need to find new ways of growing food."

Although eating insects may sound like a strange prospect to some people, such broad-minded thinking may be necessary at a time when human population growth shows no signs of slowing down.

The world's population is projected to hit 11 billion by 2100, and exactly how the planet will feed this growing population is one of the biggest questions society faces in the coming years, experts say. The new 2100 population estimate, released in a new U.N. report in June, is 800 million more people than previously predicted by that time. Much of the increase is due to birthrates in Africa not falling as quickly as expected. [What 11 Billion People Mean for the Planet]

However, the world's future food security is not a simple matter of producing more food. Rather, food security relies upon a number of intertwining factors, including population size, climate change, food production, food utilization (for things like animal feed and biofuels) and prices, experts say. Humans also have to pay close attention to their use of the Earth's resources, or risk making the situation worse, according to the World Resource Institute, a nonprofit organization that aims to protect the Earth for current and future generations.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Experts agree the planet can definitely produce enough food for 11 billion people, but whether humans can do it sustainably, and whether consumers will ultimately be able to afford that food, are not guarantees. Feeding the growing population will likely require a number of different strategies — from creating new crop varieties and reducing food waste to, yes, eating insects — with efforts from governments, farmers, the private sector and consumers themselves.

"The world's facing a great balancing act," said Craig Hanson, director of the People & Ecosystems Program at WRI. "On the one hand, the world needs to feed more people," Hanson said. "At the same time, you want agriculture to continue to advance economic and social development. And we've got to reduce agriculture's impact on the environment." There's no easy way to meet all of those demands, Hanson added.

Challenges

To feed just 9 billion people (the estimated population in 2050) would require a 60 percent increase in the number of food calories available for human consumption, according to WRI, based in Washington, D.C. When taking into account food needed to feed livestock, the world needs to increase crop production by 103 percent, or 6,000 trillion calories per year, according to WRI, which released a series of reports this year about the world's food security future.

One obstacle to increasing food production will be climate change, which is predicted to reduce crop yields in certain parts of the world. A 2009 study published in the journal Science found that, in 2100, regions in the tropics and subtropics are very likely to experience unprecedentedly warm temperatures during the growing season, reducing crop yields in the tropics by 20 to 40 percent. About 3 billion people, or nearly half the world's population, live in the tropics and subtropics, and the population in these regions is growing faster than anywhere else, the researchers said.

Extreme weather events, such as heavy rains and flooding, as well as drastic changes in weather in a short period will also pose challenges for crop production, said Walter Falcon, deputy director of the Center on Food Security and the Environment at Stanford University.

Falcon pointed out that while U.S. agriculture was affected by drought in 2012 — the most extensive drought since the 1950s — farmers had to contend with the opposite, heavy rains, this year. Rains can prevent farmers from planting their crops at the optimal time, or prevent them from planting altogether in certain areas that are flooded, said Falcon, who owns a farm in Iowa that was hit by the drought.

Changes to the food supply — which can occur when crop production is reduced by extreme weather events or when countries designate a portion of food crops to be turned into fuel, like the United States does with 40 percent of its non-exported corn crop — can push up food prices and affect people's ability to afford food. Using corn to produce ethanol has caused corn prices to increase, Falcon said.

In the midst of last year's drought, corn prices rose 50 percent, to $8 a bushel. Because corn is also used for animal feed, an increase in corn prices can affect the cost of other foods. "Corn is kind of a linchpin commodity," Falcon said. Most experts don't think the United States will increase the amount of corn that goes to ethanol in the near future, but over the course of the century, that could change, Falcon said.

Improving trade cooperation

To continue to feed a growing population in light of the food shortages that are likely to occur with climate change, global crop production in the future will have to be much more coordinated than it is today, said Jason Clay, an expert in natural resources management at the World Wildlife Fund (WWF).

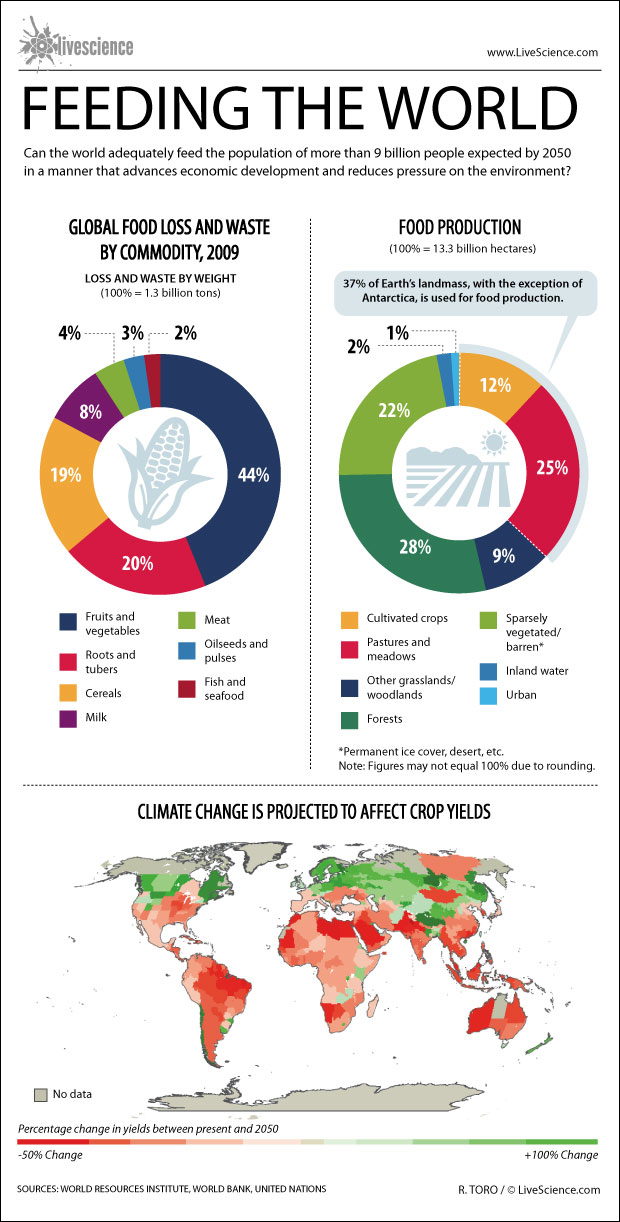

"We're going to have to work to make sure that we have a global food system that takes care of everybody," Clay said. Because extreme weather events may cause crop yields to be destroyed in certain parts of the world in a given year, such a system should be able to shift food from areas that have plenty to those that have less, Clay said. [Can the World Feed 11 Billion People? (Infographic)]

Falcon agreed. Currently, certain restrictions on trade exist that may prove problematic in the future, such as when countries ban exports if their crop production is down. The idea that each country should be self-sufficient in food production is not the answer, Falcon said.

"In a world of lots of [climate] variation, there is a lot of work to be done in getting trade flows straightened out," Falcon said.

Reduce food waste

Another strategy to help ensure food security in a world with so many hungry mouths to feed is to simply reduce food waste. One out of every four calories that's produced for human consumption today is lost or wasted, according to WRI. (Food loss refers to food that spoils, spills, etc., before it reaches the consumer, while food waste refers to food that is discarded by the consumer, either when it is still edible, or after it spoils due to negligence, according to WRI.) The average American household loses $1,600 a year on wasted food, Hanson said.

Some 56 percent of global food loss and waste occurs in the developed world — particularly in North America and Oceania, where about 1,500 calories are lost or wasted per person per day, WRI reported. In developed countries, the majority of food is wasted at the consumption stage, whereas in developing countries, most food loss occurs during production, handling and storage.

A number of changes could reduce food loss and waste around the world. For example, better storage facilities on farms in Africa — and even putting harvested crops in plastic storage bags — would reduce the amount of food that falls victim to pests there, Hanson said.

And using simple plastic crates — instead of bags and sacks — to transport food to market can reduce food damage, such as bruising and smashing, that would otherwise cause goods to be inedible. Introducing plastic crates to farmers in a town in Afghanistan — a $60,000 project sponsored by the nonprofit international development organization CNFA — reduced tomato losses from 50 percent to 5 percent, according to WRI.

At home, Americans can reduce the amount of food they throw away, perhaps by eating leftovers, or not preparing more food than they'll need for a given meal, Hanson said.

Americans also commonly have misperceptions about the meaning of labels with dates on foods, and may throw away food before it has really "gone bad," according to a WRI report. These labels, which typically read "sell-by," "best if used by" or "use-by," refer to the quality or flavor of the food, but not to food safety (whether the food would cause someone to be sick). "So while food that has passed its 'sell-by' date might be less desirable than newly purchased food, it is often still entirely safe to eat," WRI reported. Governments may be able to help by creating guidelines on what types of labels should appear on packages, and then explaining to consumers what the labels mean, according to WRI.

Eat differently

Even with less wasted food, the world could not support 11 billion people who eat the way Americans do today, said Jamais Cascio, a distinguished fellow at the Institute for the Future, a think tank in Palo Alto, Calif. Feeding 11 billion people would require a different diet, which may involve eating less meat, or consumers growing more of their own food, Cascio said.

Beef, in particular, is a very unsustainable food to eat, Cascio said. "If we get away from thinking that feeding 11 billion people means giving them all Big Macs and steak sandwiches, then we're at a better starting point," Cascio said. According to an analysis by Cascio, the greenhouse gas emissions generated by the production of cheeseburgers in the United States each year is about equal to the greenhouse gas emissions from 6.5 million to 19.6 million SUVs over a year (There are about 16 million SUVs on U.S. roads, Cascio said.) [6 Ways to Feed 11 Billion People]

Scientists have been working on developing cultured meat, or meat grown in a lab, Cascio said. Earlier this year, researchers in the Netherlands showcased their lab-grown burger, and allowed a taste test. However, right now, the cost is exorbitant (a single burger costs $325,000), and it does not taste exactly like meat (taste-testers said the burger was dry). But with future research, the price is likely to come down, and the product's taste could improve, Cascio said.

And don't forget the insects. Beetles, wasps, grasshoppers and other insects are very efficient at converting the food they eat into body mass, take up very little space and emit fewer greenhouse gases than livestock, according to the U.N.'s FAO report. Although eating insects comes with an "ick factor" for many Westerners, bugs are a part of the diet of about 2 billion people worldwide, according to the report.

Grow differently

Farmers could also focus on growing crops that provide the most calories while using the fewest resources, said Clay, of the WWF. Bananas and plantains are examples of crops that provide a lot of calories compared with the resources it takes to grow them, Clay said.For instance, 1 kilogram of bananas (2.2 lbs.) contains about 1,000 calories, and uses about 500 to 790 liters of water to grow. On the other hand, producing 1,000 calories of beef takes about 5,133 liters of water. (One kilogram of beef contains about 3,000 calories and requires about 15,400 liters of water to produce.)

In addition, crop production in certain parts of the world is not very efficient, Clay said. Efforts should be made to improve crop production in those areas, using the foods that are already grown and eaten by the people there, Clay said. Some native crops — such as pigeon peas and pulses in South Asia, and cowpeas and millet in Africa — have not yet benefited from plant-breeding techniques that could improve productivity, he said.

Innovations from scientists to come up with hardier crops, either through genetic engineering or traditional crop-breeding techniques, may also help protect against crop losses in the future due to extreme weather conditions, said Tim Thomas, an economist at the Washington, D.C.-based International Food Policy Research Institute, an international nonprofit organization that aims to find sustainable solutions for ending world hunger and poverty.

"You could picture developing varieties that are resilient to more than one shock," Thomas said, referring to varying weather and climate conditions, such as rains, flooding and heat.

Such a strategy would be similar to the one employed in the green revolution, in which research and development was used to increase crop production worldwide from the 1940s to 1970s.But this time, humans will have to work with the land they have, rather than bringing new land into production, Thomas said. Improving crop varieties will help use land more efficiently, he said.

"We need a new green revolution," Thomas said.

Follow Rachael Rettner @RachaelRettner. FollowLiveScience @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on LiveScience.

Rachael is a Live Science contributor, and was a former channel editor and senior writer for Live Science between 2010 and 2022. She has a master's degree in journalism from New York University's Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program. She also holds a B.S. in molecular biology and an M.S. in biology from the University of California, San Diego. Her work has appeared in Scienceline, The Washington Post and Scientific American.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus