'Textbooks will need to be updated': Jupiter is smaller and flatter than we thought, Juno spacecraft reveals

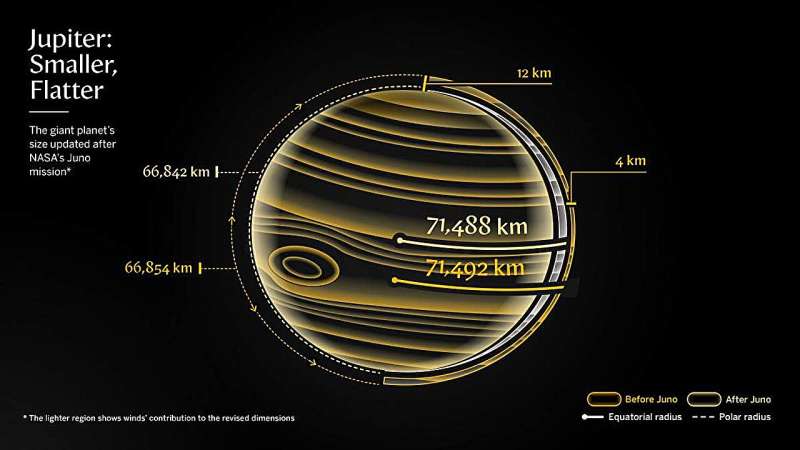

Jupiter is smaller and flatter than scientists previously thought, new measurements of the gas giant reveal.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Jupiter is slightly smaller and flatter than scientists thought for decades, a new study finds.

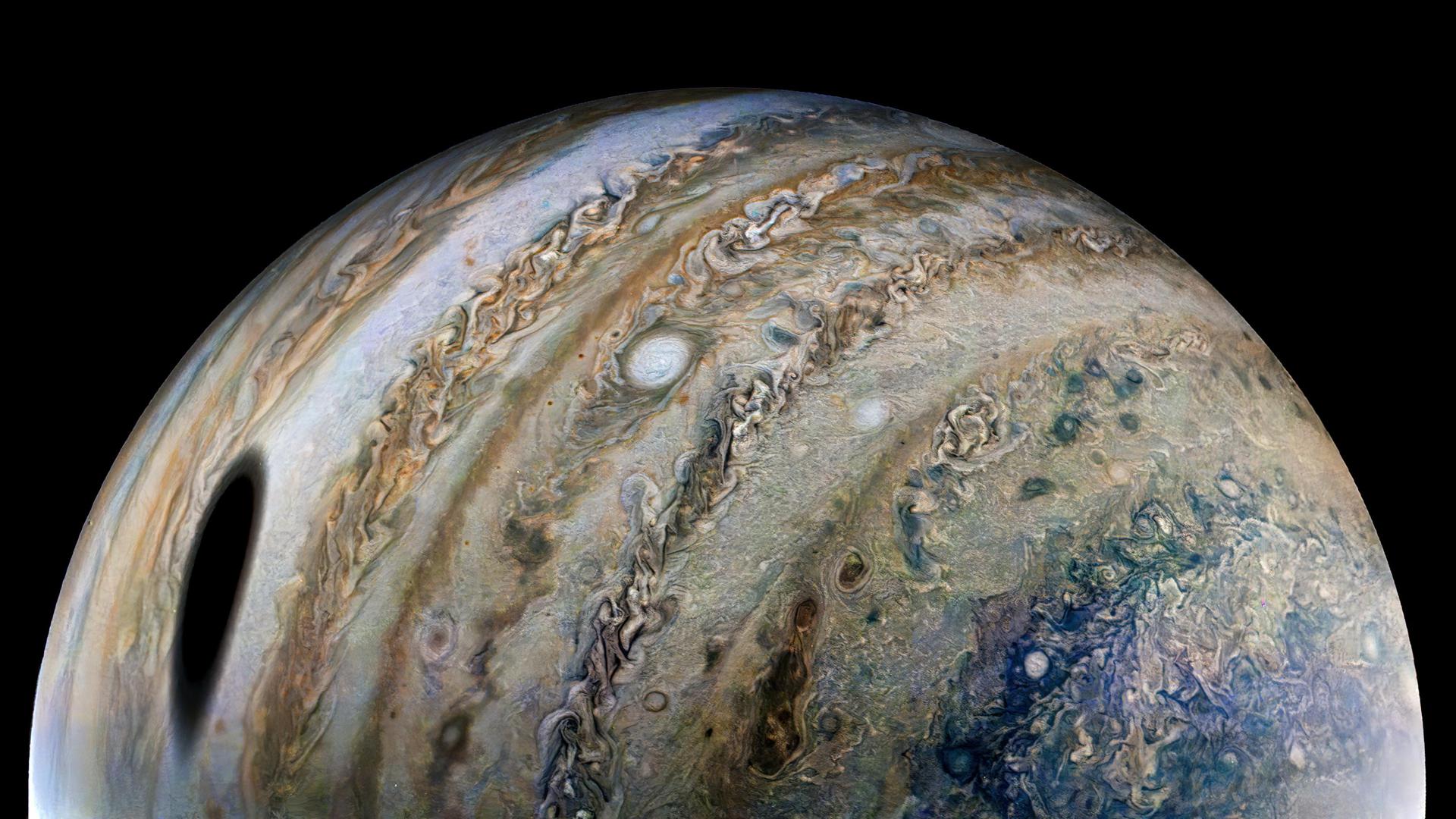

Researchers used radio data from the Juno spacecraft to refine measurements of the solar system's largest planet. Although the differences between the current and previous measurements are small, they are improving models of Jupiter's interior and of other gas giants like it outside the solar system, the team reported Feb. 2 in the journal Nature Astronomy.

"Textbooks will need to be updated," study co-author Yohai Kaspi, a planetary scientist at the Weizmann Institute of Science in Israel, said in a statement. "The size of Jupiter hasn't changed, of course, but the way we measure it has."

Article continues belowUntil now, scientists' understanding of Jupiter's size and shape have been based on six measurements performed by the Voyager 1 and 2 and Pioneer 10 and 11 missions. Those measurements, which have since been adopted as standard, were performed around 50 years ago using radio beams, according to the statement.

But the Juno mission, which has been gathering data on Jupiter and its moons since it arrived at the gas giant in 2016, has collected much more of this radio data in the past two years. With that additional data, researchers have now refined measurements of Jupiter's size down to about 1,300 feet (400 meters) in each direction.

"Just by knowing the distance to Jupiter and watching how it rotates, it's possible to figure out its size and shape," Kaspi said. "But making really accurate measurements calls for more sophisticated methods."

Bending light

In the new study, the scientists tracked how the radio signals from Juno back to Earth bent as they passed through Jupiter's atmosphere, before cutting out when the planet blocked the signal entirely. Those measurements allowed the team to account for Jupiter's winds, which slightly alter the shape of the gaseous planet. Then, they used that information to make precise calculations of the planet's shape and size.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

With the new data, the team calculated that the planet's radius from its pole to its center is 41,534 miles (66,842 km) — 7.5 miles (12 km) smaller than previous measurements. The newly calculated radius at the equator is 44,421 miles (71,488 km) — 2.5 miles (4 km) smaller than previously thought.

"These few kilometers matter," study co-author Eli Galanti, an expert on gas giants at the Weizmann Institute of Science, said in the statement. "Shifting the radius by just a little lets our models of Jupiter's interior fit both the gravity data and atmospheric measurements much better."

The updated measurements will improve our understanding of Jupiter's interior, as well as help scientists interpret data from gas giants beyond the solar system, the researchers wrote in the study.

"This research helps us understand how planets form and evolve," Kaspi said in the statement. "Jupiter was likely the first planet to form in the solar system, and by studying what's happening inside it, we get closer to understanding how the solar system, and planets like ours, came to be."

Galanti, E., Smirnova, M., Ziv, M., Fonsetti, M., Caruso, A., Buccino, D. R., Hubbard, W. B., Militzer, B., Bolton, S. J., Guillot, T., Helled, R., Levin, S. M., Parisi, M., Park, R. S., Steffes, P., Tortora, P., Withers, P., Zannoni, M., & Kaspi, Y. (2026). The size and shape of Jupiter. Nature. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41550-026-02777-x

Skyler Ware is a freelance science journalist covering chemistry, biology, paleontology and Earth science. She was a 2023 AAAS Mass Media Science and Engineering Fellow at Science News. Her work has also appeared in Science News Explores, ZME Science and Chembites, among others. Skyler has a Ph.D. in chemistry from Caltech.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus