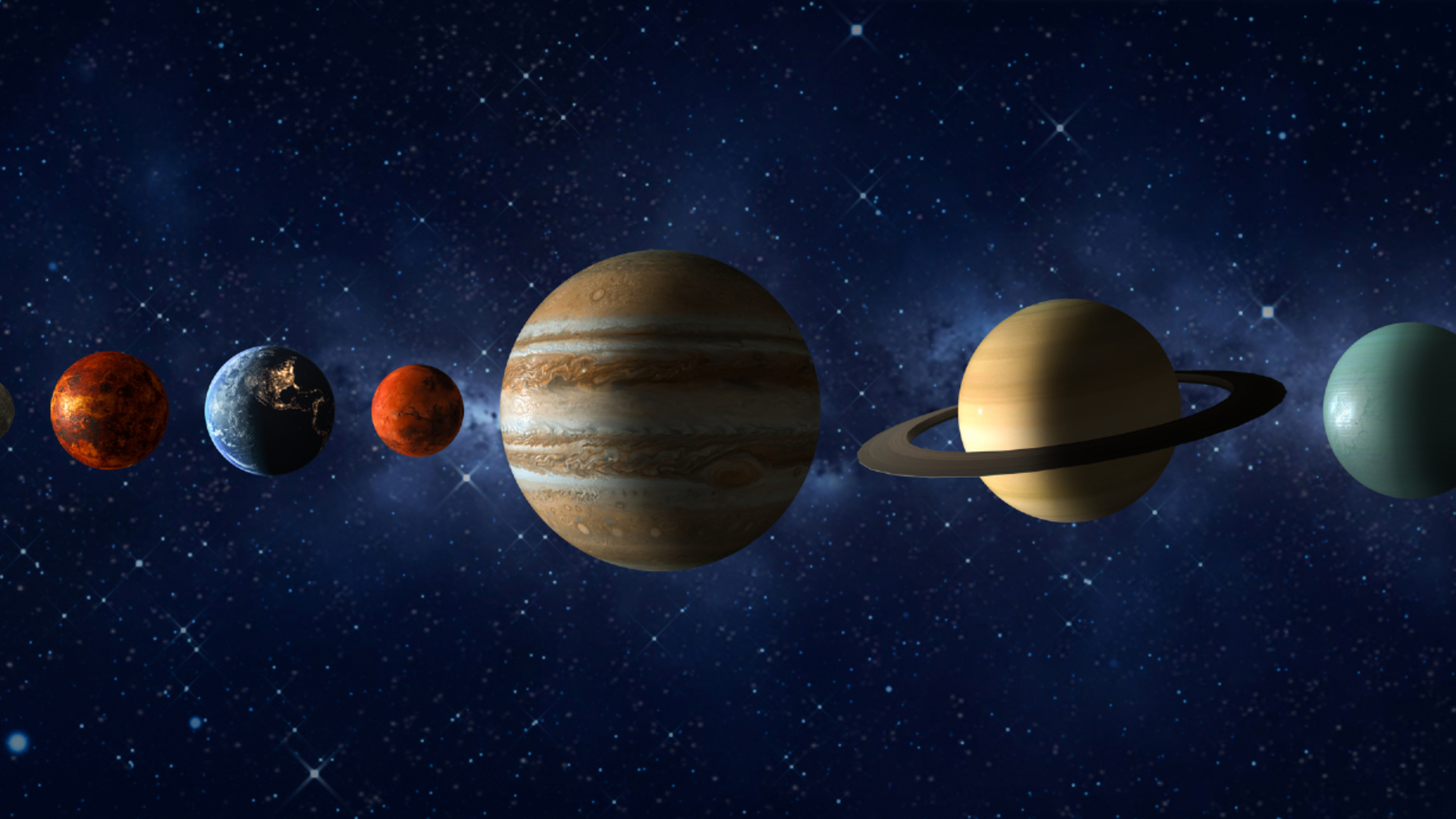

Rare 'planetary parade' will return to the evening sky this week — but you'll have to look at exactly the right time

Six planets will shine together in the evening sky on Feb. 28. Here's how to get the best view before they disappear.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

A planetary parade is about to bring six of Earth's neighbors into the night sky at once — but it won't be easy to see.

If you can find an unobstructed view due west and clear skies on Saturday, Feb. 28, you may see the two inner planets, Venus and Mercury, close to Saturn, with Neptune, Uranus and Jupiter also in the night sky, according to NASA.

The window will be tight, with Venus, Mercury, Saturn and Neptune appearing only briefly after sunset. Venus, Mercury and Saturn should all be visible to the naked eye, though a pair of stargazing binoculars may be helpful. Venus and Mercury will be closest to the horizon during twilight, with Saturn above.

Neptune will be right next to Saturn, but a 6-inch (15 centimeters) skywatching telescope will be required to get a good view of Neptune (and, in twilight, even that's unlikely). These four planets will be in the sky about half an hour after sunset and remain so for around 45 minutes.

Once you've observed Venus, Mercury, Saturn and Neptune, look high in the south for Jupiter in the constellation Gemini. It will shine very brightly, so it should be easy to find. The three stars of Orion's Belt will be roughly halfway between the other four planets and Jupiter. The giant planet will also appear as a steady, whitish light that doesn't twinkle as stars do.

Uranus, the Pleiades and a total lunar eclipse

The seventh planet, Uranus, will also be in the night sky, but it will be best seen with binoculars or a small telescope. To find it, use Orion's Belt again, following its three stars — Alnitak, Alnilam and Mintaka — upward, until you get to the shimmering sight of the Pleiades open cluster (also called "The Seven Sisters" or M45). Uranus will be just below the Pleiades, in the constellation Taurus.

As a bonus, on Feb. 28, the moon will also be in the night sky alongside another famous star cluster. About 92%-illuminated, the waxing gibbous moon will move close to the Beehive Cluster (also called M44 and NGC 2632), a bright cluster of around 1,000 stars that's about 577 light-years from the solar system.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

As the planetary parade fades, something arguably more spectacular takes its place: a total lunar eclipse on March 3 as the full "Worm Moon" passes through Earth's dark shadow. During this event, also dubbed a "blood moon," the lunar surface will turn a reddish-copper color for 58 minutes, with the best views of the entire eclipse sequence from the western U.S. (including Alaska and Hawaii), the Pacific islands, New Zealand, Australia and East Asia.

Jamie Carter is a Cardiff, U.K.-based freelance science journalist and a regular contributor to Live Science. He is the author of A Stargazing Program For Beginners and co-author of The Eclipse Effect, and leads international stargazing and eclipse-chasing tours. His work appears regularly in Space.com, Forbes, New Scientist, BBC Sky at Night, Sky & Telescope, and other major science and astronomy publications. He is also the editor of WhenIsTheNextEclipse.com.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus