Jupiter is shrinking and used to be twice as big, mind-boggling study reveals

Astronomers have calculated that the gas giant Jupiter used to be twice as big as it is now, based on the odd orbits of two of its many moons.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

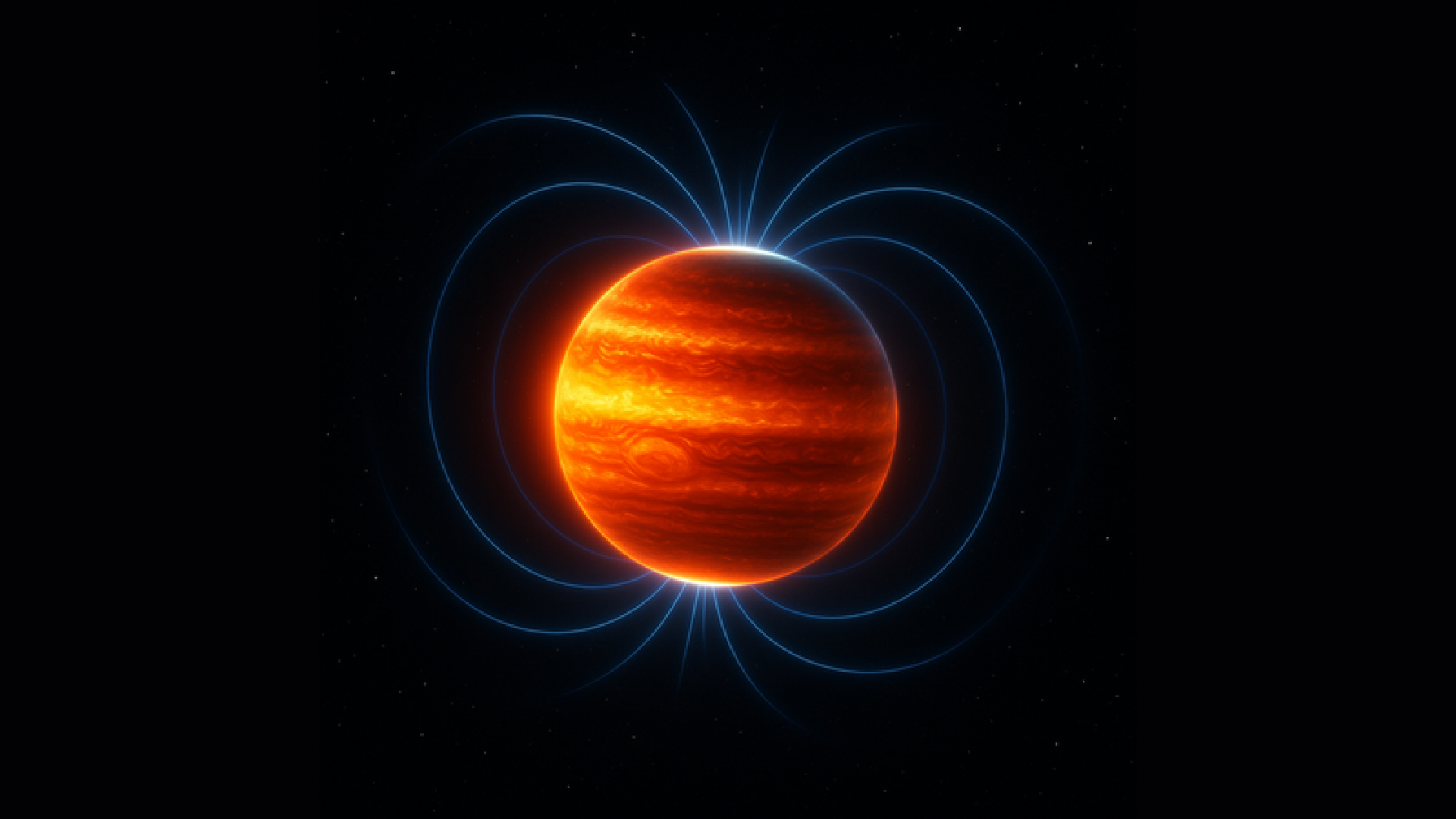

Jupiter, the solar system's largest planet, used to be even bigger, according to a new study.

The cloud of gas and dust from which the sun and planets formed dissipated around 4.5 billion years ago. At that time, Jupiter was at least twice its current size, and its magnetic field was about 50 times stronger, researchers found. The findings, which the team described in a study published May 20 in the journal Nature Astronomy, could help scientists develop a clearer picture of the early solar system.

"Our ultimate goal is to understand where we come from, and pinning down the early phases of planet formation is essential to solving the puzzle," study co-author Konstantin Batygin, a planetary scientist at Caltech, said in a statement. "This brings us closer to understanding how not only Jupiter but the entire solar system took shape."

Jupiter's immense gravity — along with the sun's — helped fashion the solar system, shaping the orbits of other planets and rocky bodies. But how the giant planet itself formed remains opaque.

To gain a better picture of Jupiter's early days, the researchers studied the present-day, slightly tilted orbits of two of Jupiter's moons, Amalthea and Thebe. The paths these moons chart are similar to what they were when they first formed, but the moons have been pulled slightly over time by their larger, volcanically active neighbor Io. By analyzing the discrepancies between the actual changes and those expected from Io's nudges, the researchers could work out Jupiter's original size.

When the solar nebula dissipated, marking the end of planet formation, Jupiter's radius would have been between two and 2.5 times its current size to give Amalthea and Thebe their current orbits, the scientists calculated. Over time, the planet has shrunk to its current size as its surface cools. Then, the team used the radius to calculate the strength of the planet's magnetic field, which would have been around 21 milliteslas — about 50 times stronger than its current value and 400 times stronger than Earth's.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"It's astonishing that even after 4.5 billion years, enough clues remain to let us reconstruct Jupiter's physical state at the dawn of its existence," study co-author Fred Adams, an astrophysicist at the University of Michigan, said in the statement.

The findings sharpen researchers' view of the solar system at a critical transition point in its history. The calculations also don't depend on how Jupiter formed — a process that's still not understood in detail — relying instead on directly observable quantities.

"What we've established here is a valuable benchmark," Batygin said in the statement. "A point from which we can more confidently reconstruct the evolution of our solar system."

Jupiter is currently shrinking by about 2 centimeters per year, according to Caltech. This is due to the Kelvin-Helmholtz mechanism — a process by which planets grow smaller as they cool. As Jupiter slowly cools, its internal pressure drops, causing the planet to steadily shrink. It's unclear when this process began.

Skyler Ware is a freelance science journalist covering chemistry, biology, paleontology and Earth science. She was a 2023 AAAS Mass Media Science and Engineering Fellow at Science News. Her work has also appeared in Science News Explores, ZME Science and Chembites, among others. Skyler has a Ph.D. in chemistry from Caltech.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus