10 Ways the Earth Changed Forever in 2019

Nothing stays the same.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Most of the time, the ground beneath our feet feels permanent. Landscapes, oceans, mountain ranges — all seem enduring compared to the human lifespan. But the Earth can change quickly and dramatically at times. The past year saw some of those moments, from wildfires that rewrote ecosystems to earthquakes that rearranged topography in an instant. Here are some of 2019's most enduring changes on Earth.

The Amazon burns

The 2019 fire season in the Amazon basin saw mind-boggling infernos tear through the largest rainforest on the planet. According to the Brazilian Institute for Space Research (INPE), the rate of fires in Brazil and the Amazon was 80% higher in 2019 than in the year before. Smoke from the fires in August turned São Paulo day into an ashy night. The fires were set by humans in attempts to clear underbrush and make way for agriculture, but drought conditions led to many of these blazes spreading out of control.

The burn scars joined with human logging to accelerate the loss of the Amazon rainforest. According to INPE, deforestation in Brazil spiked by 278% in July 2019, a loss of 870 square miles (2,253 square kilometers) of vegetation in that month alone.

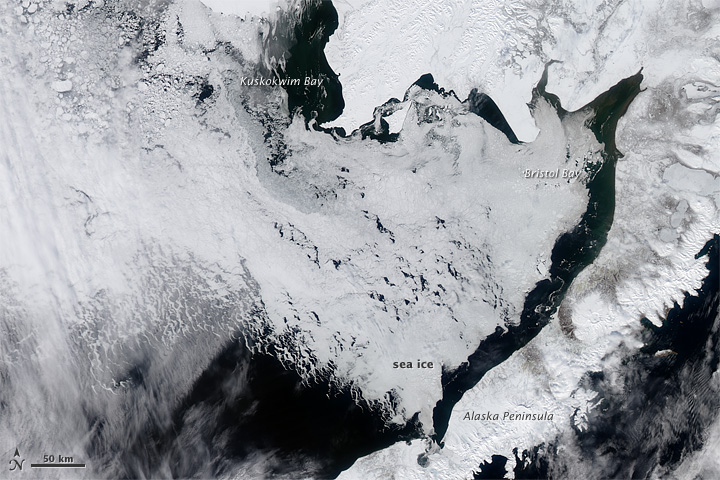

Arctic sea ice thinned

In the continuation of another sobering trend, 2019 saw Arctic sea ice continue to dwindle. Increasingly, ice-free seas are the future in the high latitudes, according to Arctic ice models. This year, this new normal asserted itself in the Bering Sea, which became almost ice-free by April. In the past, sea ice hit its maximum in April and persisted until the melt started around May.

Meanwhile, researchers found this year that the Arctic's oldest, thickest sea ice — which typically persists for more than five years — has been vanishing twice as fast as young sea ice. Researchers estimate that Arctic sea ice may disappear seasonally by 2044. The past year made it clear that the change is well underway.

A deadly landslide in Jayapura

In March, relentless rains turned steep hillsides in Indonesia's Papua region into rivers of mud and debris. More than 100 people were killed and almost as many went missing when landslides tore through villages. Flash floods drove thousands of residents from their homes, according to the Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies. The rain fell over steep slopes in the region's Cyclops Mountains, many of which have been deforested for agriculture; the resulting flooding and landslides left deep scars on the slopes and contaminated reservoirs used for drinking water.

Peru rocked by earthquake

At 2:41 a.m. local time on May 26, a magnitude-8.0 earthquake struck near the small town of Yurimaguas, Peru. The death toll was limited to one, thanks to the quake's remote location and deep origin point in the Earth's crust. But the quake also released the energy equivalent of 6,270,000 tons of TNT, permanently altering the landscape. Banks crumbed on the Huallaga River, landslides tore through hillside vegetation and roads cracked.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

A volcano rumbled to life

The Raikoke volcano, a remote mountain on the archipelago of volcanic peaks between Russia's Kamchatka peninsula and Japan's Hokkaido Island, had been quiet since 1924 — until this year. On June 22, Raikoke blew its top, sending a mushroom-shaped cloud of ash 43,000 feet (13 kilometers) into the atmosphere.

The remoteness of the eruption meant that it seriously affected only air travel, forcing planes to divert to avoid the ash cloud. But an employee on a cruise ship that came close to the island the day after the eruption was able to photograph the sudden change in the once-sleepy volcano. The slopes of the mountain were covered with inches of thick, light ash, and flows of ash and debris many feet thick had traveled down the volcano's flanks, according to the Smithsonian Institution's Global Volcanism Program. The island's vegetation was smothered in the ash.

Earthquake Island vanished

As quickly as it arrived in 2013, Pakistan's "Earthquake Island" disappeared in 2019.

Earthquake Island was produced during a 7.7-magnitude earthquake that killed more than 800 people in southwestern Pakistan in September 2013. As the Arabian tectonic plate and the Eurasian plate ground together, buried mud shot toward the surface, carrying rocks and boulders with it. The resulting island protruded 65 feet (20 m) above the ocean surface, and measured 295 feet (90 m) wide and 130 feet (40 m) long.

This year, erosion wiped away all but a few sediment traces of Earthquake Island. NASA researchers say that this short life span is common for islands produced by "mud volcanoes," the term for deep mud and rock being ejected through fissures in the crust.

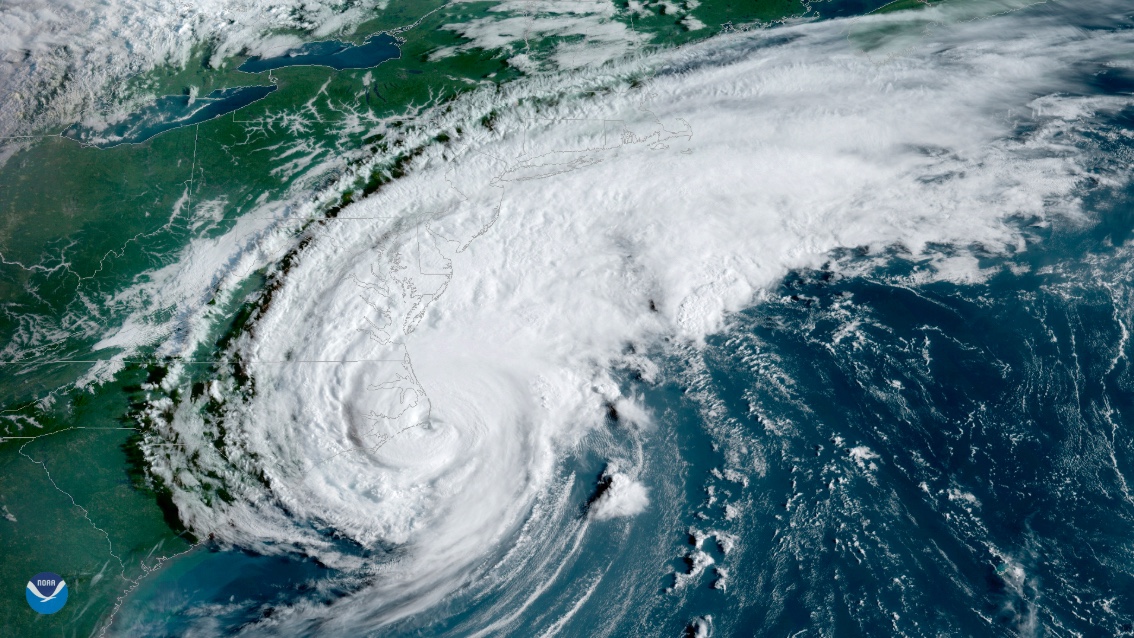

Dorian devastated the Bahamas

On Sept. 1, 2019, Hurricane Dorian rolled over the Bahamas as a slow-moving Category 5 storm, subjecting the Abacos Islands and Grand Bahama Island to hours of heavy rains and winds topping out at 185 miles per hour (295 km/h). On Sept. 3, as the storm moved away, 60% of Grand Bahama Island was underwater, according to satellite imagery captured by the Finnish firm ICEYE SAR Satellite Constellation.

The hurricane devastated the human infrastructure on the islands and killed dozens of people. The storm also damaged much of the Bahama's natural ecosystem, tearing up trees and threatening wildlife that relies on the islands' ecology. Scientists worry that the disturbance may have killed the last Bahama nuthatches (Sitta pusilla insulari) in the world. These small birds, which are found only on Grand Bahama, were down to just a few individuals after Hurricane Matthew hit the island in 2016. It's unconfirmed if any of the birds made it through Hurricane Dorian, but the monster storm and saltwater flooding hit the birds' forest habitat hard, leading to fears that Dorian was the nail in the coffin for this rare and endangered species.

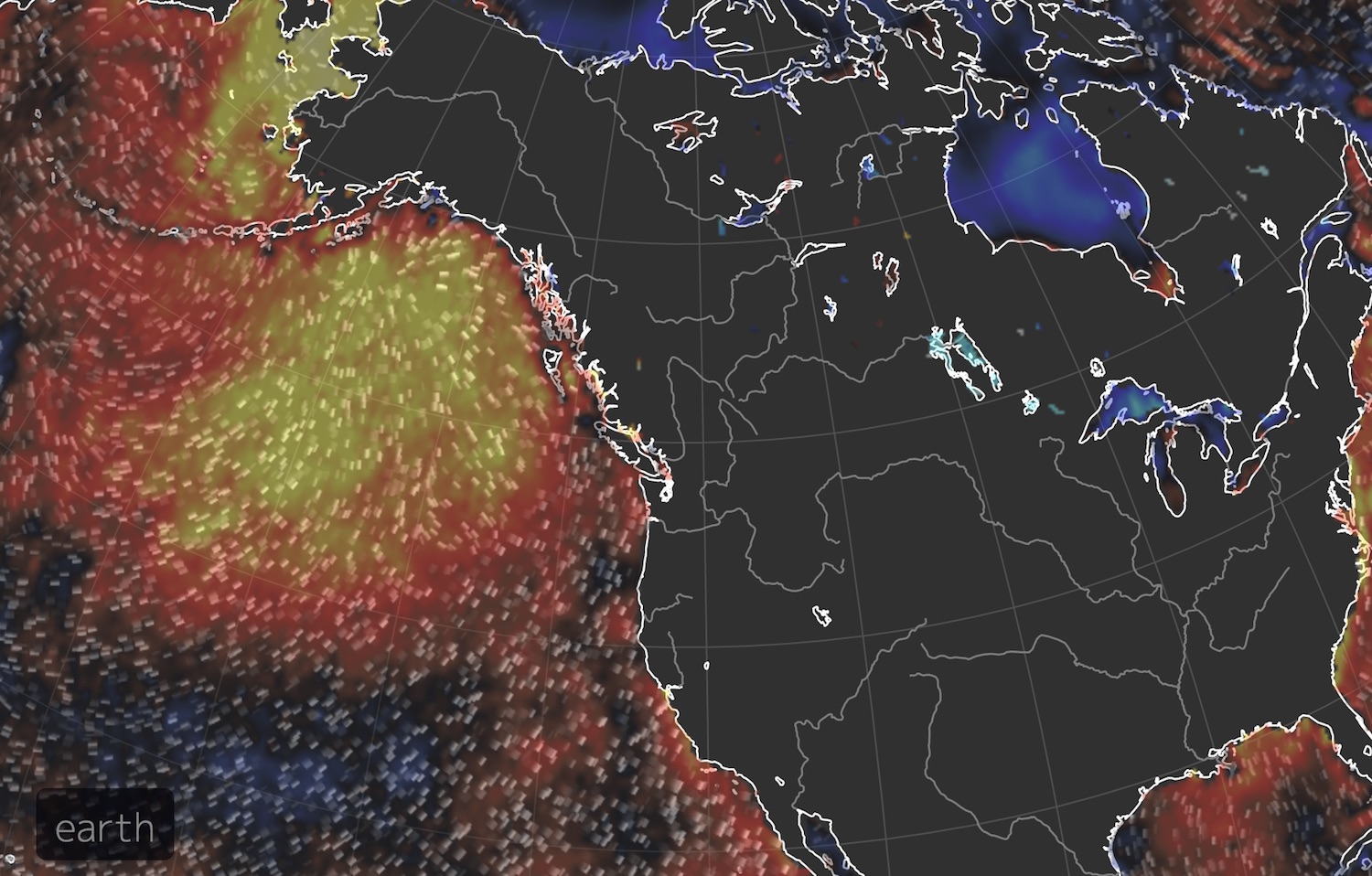

The Pacific got warmer

As the Atlantic reeled from Dorian, the Pacific experienced a marine heatwave of unusual significance. The event in the Pacific was a near-repeat of "The Blob," a huge expanse of unusually warm water that persisted off the U.S. west coast from 2013 to 2016. According to the California Current Marine Heatwave Tracker, the 2019 version of the blob was nearly as large and warm as the previous event, which affected salmon and other marine life. Sea-surface temperatures in the blob were 5.4 degrees Fahrenheit (3 degrees Celsius) hotter than average.

These heat waves are, by definition, transitory events, not permanent increases in sea temperature. But scientists are increasingly worried that these heat events will become the new normal. "We learned with 'the Blob' and similar events worldwide that what used to be unexpected is becoming more common," Cisco Werner, director of scientific programs at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, said in a NOAA news piece released in September.

Antarctica lost a tooth

Better late than never? An iceberg that scientists expected to crack off Antarctica by 2015 finally made its move in September.

The chunk of ice 632 square miles (1,636 square kilometers) in size rifted from the icy continent on Sept. 26;.it broke off the Amery Ice Shelf in East Antarctica. That ice formation seems to calve large 'bergs every 60 to 70 years, scientists reported.

Despite the change in Antarctica's coastline, the iceberg was already floating, so its calving did not affect sea levels. However, ice loss in Antarctica is accelerating — scientists estimate that the continent has lost 3 trillion tons in the last 25 years, translating to 0.3 inches (8 millimeters) of sea-level rise.

The atmosphere got more carbon-rich

Perhaps the most far-reaching change to the planet in 2019 was the continued pumping of carbon into the oceans and atmosphere, which hit a record high this year.

According to a report by the Global Carbon Project, human activity — from agriculture to transportation to industry — emitted approximately 43.1 billion tons of carbon in 2019. That makes 2019 a record-setter, breaking the previous high set in 2018. Excess carbon in the atmosphere remains there for decades to centuries, so the emissions released in 2019 will reverberate far into the future. According to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), without a rapid reduction of greenhouse gas emissions, the atmosphere is expected to warm 5.4 F (3 C) above pre-industrial levels by 2100.

- The 10 Strangest Animal Stories of 2019

- 16 Times Antarctica Revealed Its Awesomeness in 2019

- 10 Times Nature Was Totally Metal in 2019

Originally published on Live Science.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus