What Are the Odds You'll Get Struck by the Falling ROSAT Satellite?

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

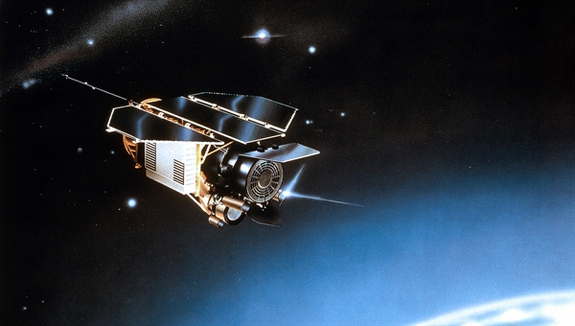

Not long after re-emerging en masse from our underground bunkers and panic rooms, having successfully avoided being squashed by a falling NASA satellite on Sept. 24, humanity has learned that the sky is falling yet again. Another huge piece of space debris, a 2.6-ton, defunct German telescope called the Roentgen Satellite (ROSAT), will crash back to Earth Saturday or Sunday (Oct. 22 or 23), and the chances it will hit someone are even greater this time around.

The odds are 1-in-2,000 that a chunk of ROSAT will strike a person. For the UARS satellite that fell into the southern Pacific Ocean in September, the odds were 1-in-3,200. According to Heiner Klinkrad, head of the European Space Agency's Orbital Debris Office, ROSAT poses a higher risk than UARS because more of its mass is expected to survive atmospheric re-entry and reach Earth's surface. [Photos: Germany's ROSAT Satellite Falling to Earth]

"The fact that the ROSAT re-entry risk estimate is higher than for UARS lies in the surviving mass, which, percentage-wise, is considerably higher for ROSAT than for UARS, and hence, the net mass reaching ground is higher for ROSAT than for UARS," Klinkrad told Life's Little Mysteries. "This is due to the ROSAT internal mirror assembly that is very resistant to [heat] during re-entry."

Typically, when a satellite crashes to Earth, only 20 to 40 percent of its mass survives; the rest burns up from heat generated by friction between the satellite and particles in the atmosphere, Klinkrad said. Because ROSAT's mirrors ? which collected X-rays and extreme ultraviolet light emitted by celestial objects ? resist heat, they reduce the percentage of the spacecraft that will burn up, and over half of the spacecraft's mass, about 1.7 tons of it, is expected to reach the surface. [If a Satellite Falls On Your Home, Who Pays for Repairs? ]

According to scientists in NASA's orbital debris office at Johnson Space Center in Houston, calculating the risk of space debris hitting someone requires first working out how much debris makes landfall. Analysts then make a grid of how the human population is distributed around the globe. Oceans, deserts and the North and South poles are largely devoid of people, for example, whereas coastlines are brimming with them. In short, the analysts must figure out which patches of Earth have people standing on them.

Throwing in a few more minor details, such as the latitudes over which satellites spend most of their time orbiting ? ROSAT will most likely fall between 53 degrees north and 53 degrees south latitudes ? the scientists calculate how likely it is that a piece of space junk will strike the ground where a person happens to be. This time around, the odds are 1-in-2,000, and there's a one-in-several-trillion chance that not only will a person get hit, but that person will be you.

Two dead satellites have crashed to Earth in as many months, after years of gradually getting dragged down to lower and lower orbits. More will re-enter the atmosphere in the future. With this in mind, you may be interested to know the overall risk of getting struck in a given year, or in your lifetime.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"The annual risk of a single person to be severely injured by a re-entering piece of space debris is about 1 in 100 billion, Klinkrad said. In the course of a 75-year lifetime, then, the odds of getting injured by space junk would be a little less than 1 in 1 billion. If this sounds scary, it probably shouldn't. By comparison, "the annual risk that a single person gets struck by a lightning is about a factor 60,000 higher, and the risk of a serious injury from a motor vehicle accident is about 27 million times higher than the risk associated with re-entry events."

- When Space Attacks: The 6 Craziest Meteor Impacts

- Will We Be Able to Deflect an Earthbound Asteroid?

- Spherical Flames and Invisible Burps: 6 Every Day Things that Happen Strangely in Space

Follow Natalie Wolchover on Twitter @nattyover. Follow Life's Little Mysteries on Twitter @llmysteries, then join us on Facebook.

Natalie Wolchover was a staff writer for Live Science from 2010 to 2012 and is currently a senior physics writer and editor for Quanta Magazine. She holds a bachelor's degree in physics from Tufts University and has studied physics at the University of California, Berkeley. Along with the staff of Quanta, Wolchover won the 2022 Pulitzer Prize for explanatory writing for her work on the building of the James Webb Space Telescope. Her work has also appeared in the The Best American Science and Nature Writing and The Best Writing on Mathematics, Nature, The New Yorker and Popular Science. She was the 2016 winner of the Evert Clark/Seth Payne Award, an annual prize for young science journalists, as well as the winner of the 2017 Science Communication Award for the American Institute of Physics.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus