Where We Store What We See

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Scientists have pinned down the region of the brain that encodes the category or meaning of visual information.

The ability to take a piece of information through our senses, assign meaning to it and categorize it helps people make sense of the world around them and behave accordingly. Because of this, when a chair is seen by the eyes, it's deemed appropriate for sitting on.

"You're not born knowing about categories or things like chairs or tables or telephones," said lead author David Freedman, a postdoctoral research fellow in neurobiology at Harvard Medical School. "Instead those develop through learning."

Monkey see

Freedman was interested in how learning gives people the ability to recognize things they see around them. And how the brain changes to encode that new information as a result of that learning.

He and colleagues trained a group of monkeys to play a computer game in which they recognized dozens of visual patterns in one of two categories.

"Once they were trained, we monitored the activity of individual neurons while they were playing," Freedman told LiveScience.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

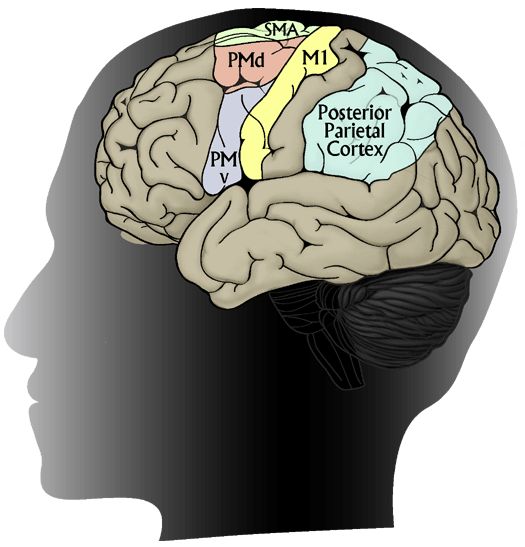

Activity in the parietal cortex, the area around the middle of the brain right around the top of the head, was completely reorganized as a result of training. The parietal neurons mirrored the monkeys' decisions about which of the two categories each visual pattern belonged to.

Learning and experience also changed how the parietal cortex represented categories.

Retraining

Over the course of few weeks, the monkeys were retrained to group the same visual patterns into two new categories. Parietal cortex activity was completely reorganized as a result of this retraining and encoded the visual patterns according to the newly learned categories, the researchers reported in the advanced online version of the journal Nature this week.

"The activity didn't just encode what those visual patterns looked like," Freedman said. "Instead, the activity encoded what those patterns actually meant or what category those patterns belonged to."

One motivation for conducting this research is to benefit those with neurological diseases such as Alzheimer's and schizophrenia.

"Once we understand how the brain does that in normal people, people that don't have brain disorders and diseases, then we'll be a step closer to understanding what's going wrong in people that have these kinds of problems," Freedman explained.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus