Newfound Eye Cells Sense Night and Day

Sometimes a discovery is right in front of your eyes. Scientists found a new class of cells in the eye that are sensitive to light responsible for regulating the body's circadian clock.

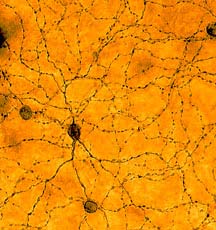

The eye's retina contains light receptors known as cones and rods. These receptors receive light, convert it to chemical energy, and activate the nerves that send messages to the brain. They were thought to be the only photoreceptors in the retina of the eye.

"When we began to do our work, we knew there might have been a missing photoreceptor,” said David Berson, professor of neuroscience at Brown University.

"We asked ourselves if there is a third class, and the answer turned out to be yes.”

The discovery was made with mice, whose eyes are thought to function similarly to humans. It was recently published in the journal Neuron.

Inside the Eye

Three-year effort

Berson's suspicion about the unknown photoreceptor class came from the knowledge that blind mice still adjusted their circadian clocks to day and night. Three years ago, Berson and his team discovered a complimentary system in the eye with photosensitive retinal cells. The full capability of the cells was not apparent, however.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

These cells, numbering about 2,000 in the eye, send electrical messages to the brain, which constricts the pupil and gives the brain information about circadian rhythms.

They are called intrinsically photosensitive retinal ganglion cells, or ipRGCs.

"Until now, we didn't know if these cells were adaptive to lighting conditions,” said Kwoon Wong, a postdoctoral research fellow in the Berson lab and the lead author of the Neuron paper. "Now we know that they are. Compared with rods and cones, they're glacially slow and they don't adjust their sensitivity as completely.”

Whereas rods and cones rapidly communicate changes in brightness and are responsible for coloring our world, the new class of cells send signals about overall brightness, somewhat like the light meter of a camera, telling the brain when it is night and when it is day.

"What's peculiar about these cells is that [unlike the rods and the cones] they are output cells, meaning they communicate directly with the brain,” Berson explained. "Rods and cones on the other hand communicate only with other retinal cells and have to go through two or three levels before they communicate with the brain.”

Better understanding

This new understanding of how the eye works may be helpful in those who are blind and have degenerated rods and cones.

"Certain people who are blind and have no conscious perception of light may still have components of a functioning visual system,” Berson told LiveScience. "This new recognition suggests being careful about procedures such as removing an eye [when deemed ineffective].”

The work also helps in understanding how biological clocks work with the rising and setting of the sun and the mechanisms involved in recovery from jetlag.

Berson and his colleagues are now hot on the question of how these cells work.

"We have this well in hand for rod and cone photoreceptors; now we have to do it all over again for this new class of photoreceptors,” Berson said. "We also need to find out how these cells interact with one another.”

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus