Only certain types of brain-training exercises reduce dementia risk, large trial reveals

A large, 20-year trial showed that speedy cognitive exercises could reduce the risk of Alzheimer's disease and other types of dementia. The question is, could these tasks be adapted into video games?

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Brain-training exercises may reduce the risk of dementia if they involve speedy thinking, whereas exercises involving memorization or reasoning have no effect on dementia risk, a two-decade-long trial suggests.

The finding could prompt researchers to design video games to help preserve users' cognitive function as they get older, some experts say.

As people age, their probability of developing Alzheimer's disease or another form of dementia increases, and these conditions affect nearly half of people in their 80s and 90s, Art Kramer, a psychologist at Northeastern University who was not involved with the new study, told Live Science. There is currently no cure for these disorders, but researchers are exploring interventions to reduce the risk of dementia. Some available drugs can help slow cognitive decline in early stages of the disease, but they're far from silver bullets.

Article continues belowNow, a trial that began in the late 1990s is pointing to non-pharmaceutical interventions that might help ward off dementia.

Weeks of training meant years of protection

At the study's start, 2,021 participants ages 65 and older enrolled in the long-term randomized controlled trial, whose results were published Feb. 9 in the journal Alzheimer's & Dementia. These participants were split into four groups. One group performed speed-training exercises, which required them to divide their attention between two tasks at once. The other three groups completed memorization exercises in which they used mnemonics; reasoning exercises that involved spotting patterns and using them to solve problems; or no cognitive exercises at all, as a point of comparison.

Participants in the three training groups completed up to 10 60- to 75-minute-long sessions over five or six weeks. Some participants also returned for up to four 75-minute-long "booster" sessions one to three years later.

Twenty years after the study began, the trial runners determined that only the speed-training exercises were linked to a reduced risk of Alzheimer’s disease and dementia. The effect was more pronounced in the booster group.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"If you were in the speed training group and you had the booster sessions, you had a 25% lower risk of having a diagnosis of dementia [by the end of the trial]," said study co-author Marilyn Albert, a neuroscientist at John Hopkins University. By comparison, dementia was just as common in the other two training groups as it was in the comparison group, suggesting the memory and reasoning tasks had no protective effect.

The trial results raise the question as to whether speed-training cognitive exercises, including certain brain-training video games or apps, could help guard against dementia.

"There are hundreds of those that exist in the marketplace" and claim to be designed to boost brain health, Kramer said. "When these things get commercial, sometimes people make claims that go beyond the data, so you always worry about that," he cautioned. But still, he argued that these games could theoretically achieve a similar effect to the speed-training cognitive exercises tested in the trial.

Albert, meanwhile, is hesitant to suggest that video games could recapitulate the effects seen in this study.

"Speed-of-processing training isn't a whole lot of fun. It's hard," she told Live Science. She argued that the most important factor of the speed-training exercises, which may be missing from video games, was that they were adaptive. They involved looking for objects in the center and at the edges of a computer screen to find two that match; the exercise would refresh faster and with more objects as performance improved.

This adaptation wasn't an element of the memory and reasoning exercises, which may explain why those didn't lead to a significantly reduced risk of dementia, Albert said.

One strength of the trial was that it included a large group of participants, a quarter of whom belonged to minority groups. "People who are Black or Hispanic have a higher risk of dementia," Albert said, arguing that their representation in the study may make the results more generalizable.

The next step is to investigate whether the exercises prompted any specific brain changes that delayed neurodegeneration.

"We need to understand the mechanisms, because if we did, then we could better design the interventions," Albert said. Kramer suggested following up with MRI scans to see how cognitive exercises alter brain anatomy in human participants.

He noted that scientists can train lab animals, such as rodents, to perform similar training exercises. "And then you can do things that are a bit more invasive," he added, such as changing the lab mice's genetic makeup to understand what genetic factors are at play.

In the meantime, scientists already know of other lifestyle factors that are tied to a lower risk of Alzheimer's disease and other forms of dementia, Albert noted. These include engaging in regular physical activity and maintaining blood pressure within the normal range. Someday, perhaps brain-training exercises will also become a common method to stave off dementia — especially since, in the trial, it took only a few weeks of training to protect the participants for 20 years, Albert said.

This article is for informational purposes only and is not meant to offer medical advice.

Coe, N. B., Miller, K. E., Sun, C., Taggert, E., Gross, A. L., Jones, R. N., Felix, C., Albert, M. S., Rebok, G. W., Marsiske, M., Ball, K. K., & Willis, S. L. (2026). Impact of cognitive training on claims‐based diagnosed dementia over 20 years: Evidence from the active study. Alzheimer’s & Dementia: Translational Research & Clinical Interventions, 12(1). https://doi.org/10.1002/trc2.70197

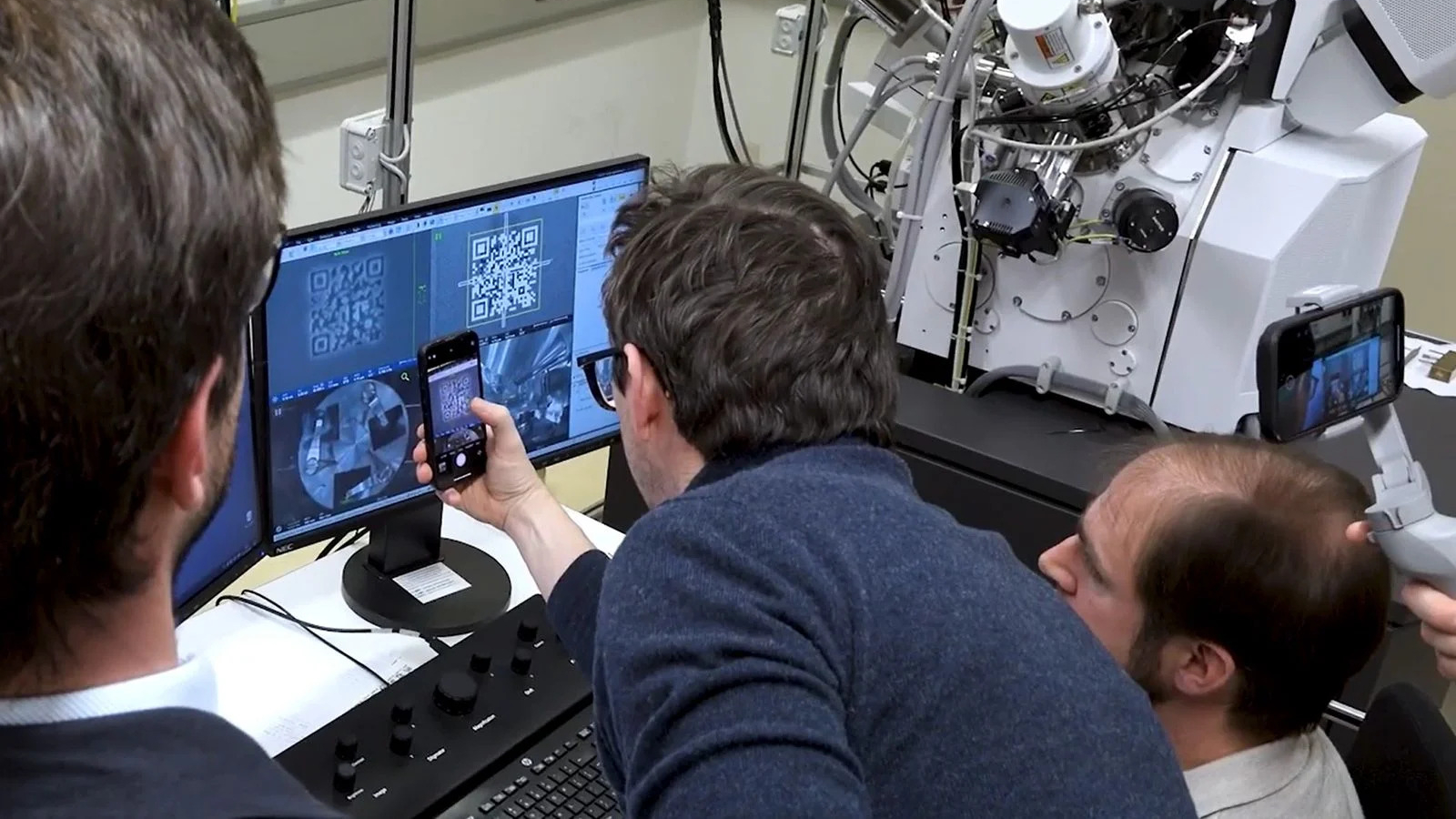

Kamal Nahas is a freelance contributor based in Oxford, U.K. His work has appeared in New Scientist, Science and The Scientist, among other outlets, and he mainly covers research on evolution, health and technology. He holds a PhD in pathology from the University of Cambridge and a master's degree in immunology from the University of Oxford. He currently works as a microscopist at the Diamond Light Source, the U.K.'s synchrotron. When he's not writing, you can find him hunting for fossils on the Jurassic Coast.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus