There's a new blood test for Alzheimer's. Here's everything you need to know about it.

In patients showing cognitive decline, a new blood test for Alzheimer's is expected to make diagnosis more convenient, accessible and inexpensive than other existing tests.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) recently cleared a blood test that detects signs of Alzheimer's disease in the brain, according to multiple studies. This is the first-ever blood test available for this common form of dementia.

Here's how the new blood test works and why it could be useful to patients.

Why do we need a blood test for Alzheimer's?

Alzheimer's disease is on the rise, in part because the age group most prone to dementia is growing larger. In the U.S., an estimated 7.2 million Americans ages 65 and older are living with Alzheimer's dementia in 2025. The percentage of affected people increases with age: About 5% of people ages 65 to 74 have Alzheimer's, compared with more than 33% of people ages 85 and older.

At the point when a doctor has verified that a patient has cognitive decline, the blood test can be used in place of standard tests to see if they likely have Alzheimer's. Previously, gold-standard methods of diagnosing Alzheimer's have been more invasive and expensive, involving positron emission tomography (PET) scans, which use radioactive substances; and lumbar punctures, (also called spinal taps) during which a clinician uses a needle to sample spinal fluid from the low back. Clinicians also sometimes use MRIs or CT scans to rule out other causes of cognitive decline.

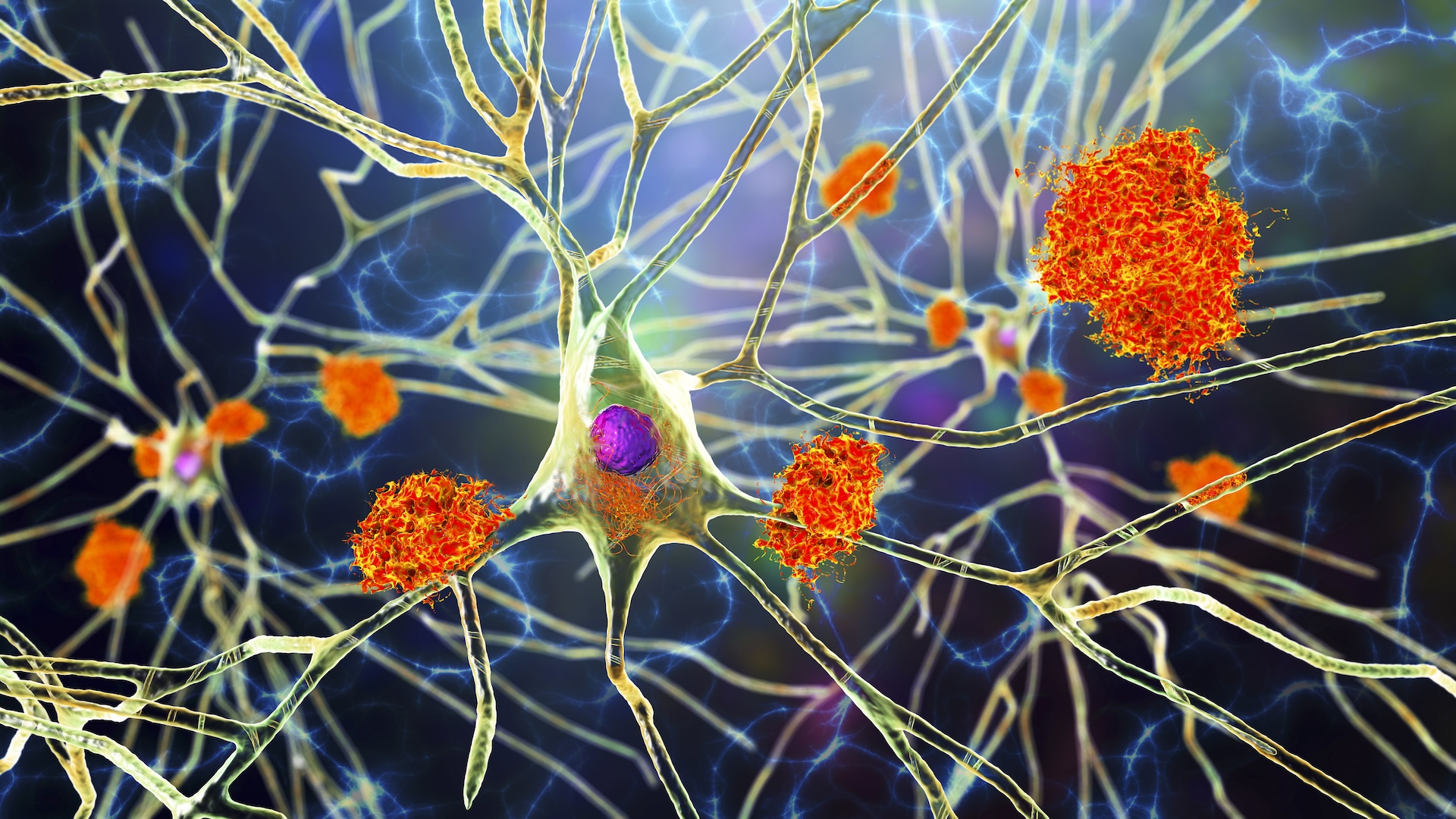

The new test measures the ratio of two proteins in human blood, and this ratio correlates with the presence or absence of amyloid plaques, a primary sign of Alzheimer's found in the brain.

For people experiencing memory lapses that might be due to Alzheimer's, the first step is to see their primary care physician (PCP), who should do a cognitive test. If there are signs of cognitive impairment, the patient would then be referred to a neurologist for an in-depth evaluation.

Both dementia specialists and PCPs will be able to order this blood test to help with diagnosis, said Dr. Gregg Day, a neurologist with the Mayo Clinic in Jacksonville, Florida; Day led a study of the blood test published in June in the Journal of the Alzheimer's Association. A study published in 2024 in JAMA found that whether the test was ordered by a PCP or specialist, it was equally accurate at confirming suspected Alzheimer's diagnoses.

PCPs could use the test results to decide whether to refer patients to a specialist, who could prescribe treatments such as lecanemab or donanemab, Day said. Or the PCP could personally prescribe a medicine like donepezil, which can help improve mental function in Alzheimer's. With FDA clearance, Medicare and private health insurance providers alike are expected to cover the new blood test, Day said.

Who should get the blood test?

The test — called the "Lumipulse G pTau217/ß-Amyloid 1-42 Plasma Ratio" — is intended for people ages 55 and older who show signs and symptoms of cognitive decline that have been confirmed by a clinician. The test is designed for the early detection of amyloid plaques associated with Alzheimer's disease. (Amyloid plaques are unusual clumps found between brain cells and made up of a type of protein called beta-amyloid.)

Related: Man nearly guaranteed to get early Alzheimer's is still disease-free in his 70s — how?

Early detection is important, said Dr. Sayad Ausim Azizi, clinical chief of behavioral neurology and memory disorders at the Yale School of Medicine. That's because the Alzheimer's brain is like a rusty engine — the plaque is like rust settling onto the engine, interfering with the wheels' ability to turn, Azizi told Live Science.

There are FDA-approved treatments that act like oil, helping the wheels to turn, but the medication does not remove the rust itself, he said. Available therapies can slow down the degradation of the brain by about 30% to 40%, studies show, so the patient can retain function for longer.

"If you're driving now and living independently and you don't take the medicine, it's likely in five years you won't be able to do all these things," Azizi said, providing a hypothetical example. "If you take the medicine, the five years are extended to eight." If adopted as intended, the new blood test could help more people access these treatments sooner.

Can the blood test be used as a general screening tool?

The test is not recommended for the purposes of screening the general population. It is intended only for people who have been found by a doctor to exhibit signs of Alzheimer's disease, Day and Azizi emphasized.

Some amount of amyloid is present in the brain during healthy aging, so its presence doesn't guarantee someone will later have Alzheimer's. If the test detects signs of amyloid plaques 20 years before any cognitive symptoms surface, Azizi explained, it would not make sense to treat the patient at that time.

"The treatments are not 100% benign," he added. To receive lecanemab, for example, patients must be able to receive an infusion every two weeks at first and every four weeks later on; donanemab is given every four weeks. Both medications can come with infusion-related reactions, such as headache, nausea and vomiting.

Rarely, the treatment donanemab can cause life-threatening allergic reactions, and both lecanemab and donanemab have been tied to rare cases of brain swelling or bleeding in the brain. These latter side effects are related to "amyloid-related imaging abnormalities," which are structural abnormalities that appear on brain scans.

Is there a risk of false positives?

The new test can give false positives, meaning a person can potentially test positive when they don't actually have Alzheimer's. That's because the signs of amyloid that the tests look for can be tied to other conditions. For instance, amyloid buildup in the brain could be a sign the kidneys are not functioning optimally, Day said, so he recommends also doing a blood test for kidney function when ordering the Alzheimer's blood test.

The Mayo Clinic study included about 510 people, 246 of whom showed cognitive decline; the blood test confirmed 95% of those with cognitive symptoms had Alzheimer's. About 5.3% of cases showed a false negative on the blood test, while 17.6% of cases gave a false positive, Day said.

Most of the false-positive patients still had Alzheimer's-like changes in their brains, but their symptoms were ultimately attributed to other diseases, such as Lewy body dementia, Day said. The Mayo study found that the blood test helped doctors distinguish Alzheimer's from these other forms of dementia.

As is true of many clinical trials, evaluations of the test have primarily included populations that are healthier than average, Day said. These individuals are not only healthier at baseline, but are more likely to have health insurance and be white and non-Hispanic.

So when the blood test is used in a broader population, there may be people with sleep apnea or kidney disease who test positive despite not having Alzheimer's, Day said. Some people with these health problems may also experience memory issues or cognitive impairment that's not caused by Alzheimer's disease. If the blood test points to amyloid buildup, doctors could order additional tests and ask patients about their sleep to help rule out these other possibilities.

Could the blood test advance Alzheimer's research?

The test will give researchers a more precise idea of how a patient's clinical symptoms relate to the findings on their blood test, Azizi said. "It's a great way of using a biomarker [measurable sign of disease] in the blood to make an earlier diagnosis to give a drug" to slow disease progression, he said.

Azizi added that this blood test could help track whether a treatment for Alzheimer's disease is working, which would be useful both for patients receiving approved medicines and those in trials of new drugs. Looking forward, researchers will also be able to evaluate how well blood-based testing works in more diverse populations, Day noted.

This article is for informational purposes only and is not meant to offer medical advice.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Theresa Sullivan Barger is an award-winning freelance journalist who covers health, science, and the environment. Her stories have appeared in The New York Times, The Boston Globe, Los Angeles Times, AARP, CURE, Discover, Family Circle, Health Central, Next Avenue, IEEE Spectrum, Connecticut Magazine, CT Health Investigative Team, and more. Based in central Connecticut, she is an advanced master gardener who is passionate about gardening for wildlife, especially pollinators and songbirds.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus